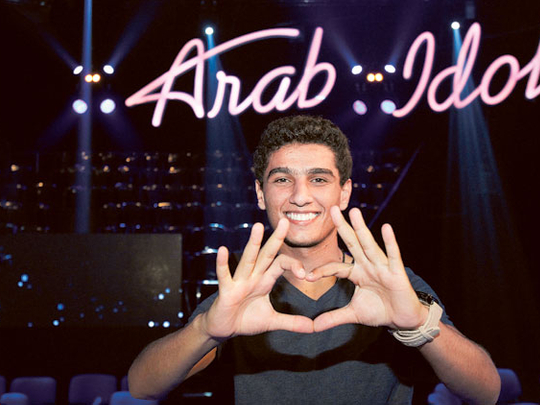

Eyes glued to big screens in cafes and restaurants across Gaza and the West Bank, adoring fans cheer on Mohammad Assaf as he sings his way closer to winning this year’s Arab Idol song contest.

Since March, the handsome, immaculately dressed 22-year-old Gazan’s powerful voice has propelled him every weekend to the ranks of only seven remaining singers in a Beirut-based competition that started out with 27.

In Gaza City and Ramallah alike, fans carry banners that urge viewers to text “number 3” to the Arab Idol hotline on their mobile phones, giving Assaf a vote. As with Pop Idol, the Western equivalent on which it is modelled, Arab Idol eliminates each week the singer with the fewest votes. Assaf made it through again on Saturday night.

“He deserves to win,” said Maya, a 19-year-old supporter who watched the show at a cafe in Gaza, smoking a shisha (water pipe) and drinking coffee. His voice is great and his presence even better; there’s none like him!”

“Assaf is competing to raise the profile of Palestine and Gaza. I support him and am proud he’s from here,” she added, smiling.

Assaf, introduced on the programme as representing “Palestine,” has featured prominently in the Israeli media and captured not only the popular imagination, but also that of prominent West Bank politicians.

He has received a personal telephone call from Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas, according to news agency WAFA, and has been endorsed on the Facebook page of caretaker premier Salam Fayyad.

Assaf began his musical career singing Palestinian nationalist songs in his hometown of Khan Yunis and aired on Palestinian TV, and his choices of song on Arab Idol retain a political tinge.

“Palestine, the north and south, two brothers in an Arab world,” he sang on a recent instalment of the show.

The competition on Arab Idol, which is broadcast from Beirut studios by the Saudi-owned MBC, is stiff. Talented young singers from across the Arab world compete.

Another one still in the running is Abdul Karim Hamdan, a native of Syria’s war-torn city of Aleppo, who likewise sings about his homeland.

This year a female Iraqi Kurdish singer, Parwas Hussain, has also made it through the latest round.

Assaf has overcome his own difficulties in making it this far, given the crippling Israeli blockade of the Gaza Strip and its rule by the Islamist movement Hamas. “Assaf beat the blockade and societal restrictions,” said Sana, watching from the same Gaza cafe.

“Gaza is not all terrorism, death and violence; it has artists who need to realise their potential and just need a bit of freedom to do so.” The blockade, which Israel imposed in 2006, tightened after Hamas took over the territory a year later. Hamas itself disapproves of what it considers un-Islamic shows, such as Arab Idol, but has not officially clamped down on support for Arab Idol or Assaf.

His popularity is palpable, with numerous giant posters featuring his image in the Strip.

Assaf, who travelled to Lebanon after crossing the Gaza border into Egypt, has remained in Beirut with the other contestants since the competition began.

Assaf’s parents are delighted with their son’s rise to stardom, but fear there is no future for his career at home. “The youth in Gaza want to live normally,” said his 50-year-old mother, Umm Shadi.

“They don’t lack talent or ambition, but they need to break out of their tough circumstances.”

And there was little room for artistic creativity in Gaza. “Politics trumps everything here.”

Jaber Assaf, the singer’s 55-year-old father, warned that if Assaf were to pursue his musical career, “he can’t stay in Gaza, because the art scene here is limited.”

Assaf, born in Misrata, Libya in 1990, started singing at five after returning to Gaza when his father finished his job in the country.