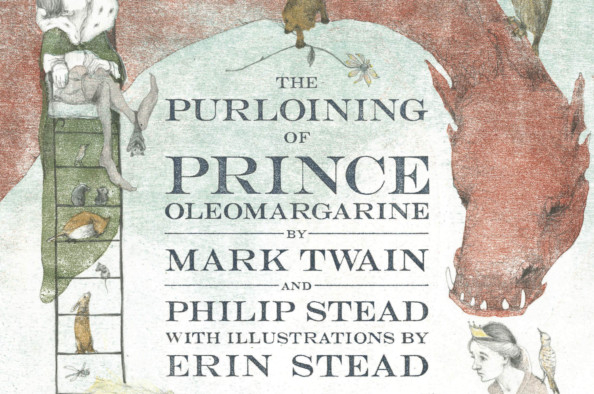

Notes that Mark Twain jotted down from a fairy tale he told his daughters more than a century ago have inspired a new children’s book, The Purloining of Prince Oleomargarine.

At the Mark Twain House and Museum in Hartford, there is excitement that the story could help introduce the writer to wider audiences — and provide a financial lift for the non-profit organisation that curates the three-story Gothic Revival mansion where Twain raised his family.

A researcher found the story in the archive of the Mark Twain Papers at the University of California at Berkeley. When the University of California Press passed on taking it to publication, the archive’s director, Bob Hirst, endorsed enlisting the Twain House as an agent in part because of financial struggles the museum has had to overcome.

“I don’t think it’s a secret they need funding,” Hirst said. “If it was going to make some money, which Mark Twain would certainly approve of, that house was a good place for it to go.”

The Twain House connected the UC Press with DoubleDay Books for Young Readers, which hired an author and illustrator to turn Twain’s unfinished notes into the book to be published in September. The publisher and others involved declined to discuss the financial terms.

Amy Gallant, the Twain House’s interim executive director, said the museum has a balanced budget and its finances are sound. Since cost overruns brought the museum to the brink of closing a decade ago, it has reported strong admissions numbers and state aid has helped with needed improvements. But Gallant said she understands the Twain House will receive royalties on book sales and she hopes it is “incredibly successful.”

The book tells the story of a boy who gains the ability to talk to animals by eating a flower from a magical seed and then joins them to rescue a kidnapped prince.

Winthrop University English professor John Bird was mining the Berkeley archive for a possible Twain cookbook in 2011 when he flagged Oleomargarine, thinking it might be related to food. After reading over the 16 pages of Twain’s handwritten notes, he realised the manuscript was a story Twain apparently told his daughters in 1879 while the family visited Paris.

The 152-page illustrated book, completed by Philip and Erin Stead, frames the narrative as a story “told to me by my friend, Mr. Mark Twain.”

The author, born Samuel Clemens in Missouri in 1835, lived with his family from 1874 to 1891 at the house in Hartford. Tours feature the home’s library and a discussion of the bedtime stories he would conjure there nightly for his three daughters.

Cindy Lovell, who recently stepped down as the Twain House director and helped shepherd the book project, said the story is exceptional because Twain was not known to write down any of the thousands of stories he told his children.

“To him, this was nothing. He never wrote it because it came so easily,” she said. “I don’t think it ever occurred to him that could have been a gold mine.”

Lovell said the Twain House will benefit financially from the book, as will the UC Press and the Mark Twain Project, led by Hirst at Berkeley.

In 2010, a Twain autobiography became an unexpected best-seller when it was published a century after his death, at the author’s request. Hirst said there are still other Twain works in the archive that could be published.

“The pile is getting smaller and smaller,” Hirst said. “He left quite a lot.”