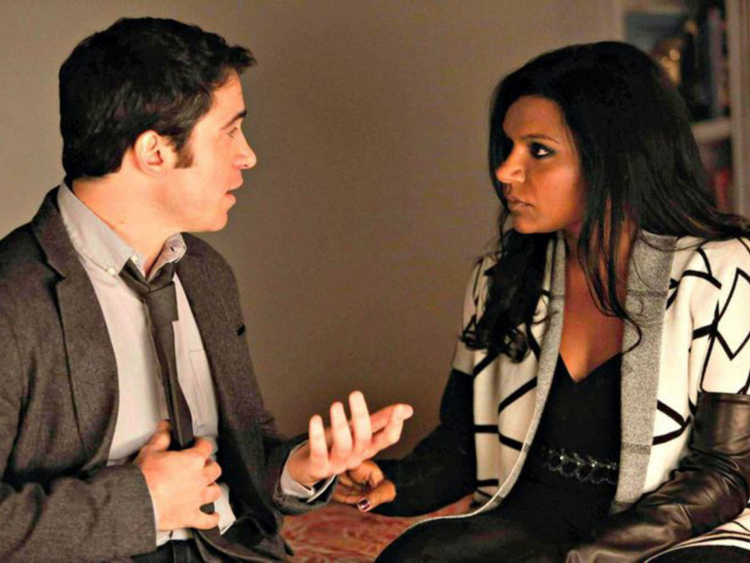

It’s not going to come as a big surprise to anyone in 2017, but romance is dead. And nowhere is that spelled out more clearly than on TV. Recently it was announced that the cutesy love-in-a-flatshare sitcom New Girl’s seventh series would be the last, with a mere eight episodes compared to its previous 22-episode runs. Similarly, The Mindy Project, Mindy Kaling’s homage to ‘90s romcoms, is about to begin filming its final, sixth series, with creator Kaling saying: “I think the timing is exactly right.”

Does the ending of these shows point to the end of the TV romcom? The answer to why this is happening might be found in the second season of Aziz Ansari’s bleak look at modern love, Master Of None. The episode ‘First Date’ summarises everything that’s wrong with romance right now: specifically that we’d rather look at our phones than our date’s face. Dating is portrayed as a soulless numbers game (see the scene where Ansari’s Dev happily admits he sends the same opening line to every girl he matches with) where someone better is just one swipe away.

Still, even Master of None can’t keep up with the pace at which love and relationships are moving in modern life. First dates are more like two drinks near your office then making up an excuse to leave. Ten years since that romcom classic Gavin & Stacey began, we now have the “anti TV romcom”, where we’re seeing couples tearing each other apart (Love, Catastrophe, You’re The Worst); cringing through a series of uncomfortable romantic scenes (Fleabag); and dysfunctionally falling apart over six seasons (Hannah and Adam in Girls).

ROMANCE v/s REALITY

Leger Grindon, professor of film studies at Middlebury College, Vermont, and author of The Hollywood Romantic Comedy, says that what we’re seeing on TV is simply reflecting how romance has evolved over time. “I met my wife by writing to a personals ad in the paper... Now, it’s dating apps. Things are more volatile,” he says. He’s right: The Mindy Project might have seen Mindy race up the Empire State Building where her work-nemesis-turned-love-interest Danny proposed to her, but wasn’t Gus waiting outside Mickey’s AA meeting an equally romantic, just slightly more modern, gesture in Love?

Ben Taylor, director of Catastrophe, says that that’s what audiences want to watch: something that reflects the reality of their lives. “People want something more authentic,” he tells us. Relationships very rarely start with a meet-cute and get made official by a big, dramatic gesture. “What I think Sharon [Horgan] and Rob [Delaney, creators and writers of Catastrophe] really, really seek to avoid is neatness. I don’t think life is neat,” Taylor says.

Tom Edge, the creator and writer of Netflix’s Lovesick (previously known as Scrotal Recall, about Dylan, who has to meet up with all of his exes to inform them he’s got an STD) points out that streaming, and the potential for binge watching, has changed how romcoms on TV play out. “I think when you have the longer span of television, having that space that allows you the capacity to kind of treat things a little more realistically. So even if you do go for the happy ending, then that happy ending can be complex,” he says.

The TV sitcom no longer needs the mid-season cliffhanger or something that will bring you back the same time next week, because streaming services will play us the next episode within 20 seconds. “Being freed from the question of overall ratings being the primary thing has meant that shows have gotten weirder,” says Edge. “I think the premium streaming shows will tend to remain kind of darker around the edges.”

The tonal change of these shows has reflected a broader outlook change. “In the ‘90s, there were shows like Mad About You, which were much more optimistically romantic, and of course Friends, while not actually a romantic comedy, the spine of it was Ross and Rachel‘s relationship,” says Edge. “A lot of those comedies had real warmth and optimism and almost took their romantic nature for granted. I feel like a lot of contemporary TV romantic comedies are a little bit more barbed, a little bit more acidic.”

Catastrophe’s Taylor agrees that this tonal change has been in keeping with the mood of the times. “Inevitablity, the stuff you’re writing and creating reflects what’s going on in the world,” he says. “At the same, I think it’s also the antidote. We’re not going to solve any major crises with a half-hour comedy.”

Director Juliet May, who worked on hyper-optimistic sitcom Miranda, thinks there’s an element of catharsis, too. “Viewers sit at home and want reassuring that other people go through rough times.”

RISE OF ANTI-ROMCOMS

Further, the structure of the romcom sitcom is changing. While the last series of New Girl ended with the show’s eternally on/off couple Jess and Nick realising that: yes, they were head over heels in love with each other, the anti-romcoms on TV now begin, rather than end with, a couple sleeping together — a more realistic beginning of a relationship. “I don’t want to speak for [Delaney and Horgan] but I’m 100 per cent sure they wouldn’t have said ‘romantic comedy’ when Catastrophe was pitched as an idea,” says Taylor. “I’m not even sure they would have said the word romantic. But I always saw it as an incredibly romantic because at the heart of it is an odd couple who you really root for. I always saw [the characters] as very much in love with each other... Pure black-hearted romantic comedy doesn’t get you very far, you need to be able to root for them.”

Another obstacle for romantic comedies on TV is the “happy ending’ structure inherited from cinema. “I think in a sitcom format, it’s actually really difficult to make it work; once the couple gets together, the tension of the show is lost,” says Variety’s Sonia Saraiya.

The Mindy Project’s writer and executive producer Matt Warburton says that both getting the show’s lead characters together and breaking them up again “was, in retrospect, extremely scary. But the alternative is three years into the show, solve all of Mindy’s problems and she has everything she wants, and all of a sudden you’ve got yourself a boring show,” he says. “Breaking up the Mindy-Danny relationship was a real life-saver for us, because it gave us an engine for endless new stories.”

Ike Barinholtz who writes, produces, directs and plays nurse Morgan on The Mindy Project says he was desperate for Mindy and Danny to split up. “I was very excited when I heard that Mindy was going to be single again. I’ve seen a show about a single girl looking for love, now we have a totally new, original thing: a show with a young Indian single mother looking for love.”

Plus, adds Warburton, they had a 26-episode season to fill. “I don’t know what we’d do with all the episodes because she was in such a good place. There are only so many times you can do Mindy and Danny fighting over who’s going to do the dishes.”

So will we see a romantic sitcom comeback on TV? Barinholtz thinks so. “I think out of tough times, you get hopefulness,” he says. “To be able to get away from your world, to have that nostalgic, fuzzy warm feeling just watching two characters discover love for the first time, it’s just a total escape. That’s definitely what romantic comedy offers.”

Saraiya adds that love and dating will always be interesting to TV audiences. “I think that there will always be a market for the romantic comedy,” she says “but what we see as romance, and what we see as funny, will be changing.”