The Wire, HBO’s five-season epic of Baltimore life, is a perennial contender for the greatest television series ever, and Michael K. Williams, in his role as stickup man Omar Little, its most memorable actor. But on the show’s first day of filming, when a prop person handed him his character’s signature shotgun, Williams clutched it with a look of sheer bewilderment.

“He didn’t know which end was which,” said David Simon, the creator and showrunner of The Wire. “Mike is a beautiful man, but a gangster he is not.”

Williams would not be deterred. Later that week, he left the set in Baltimore and returned home to Brooklyn and enlisted a local drug dealer to help hone his craft. Standing on the roof of the Vanderveer Estates, the man walked him through the particulars of firearms by spraying a hail of pellets into a steel door.

“Best acting lesson I ever had,” Williams said.

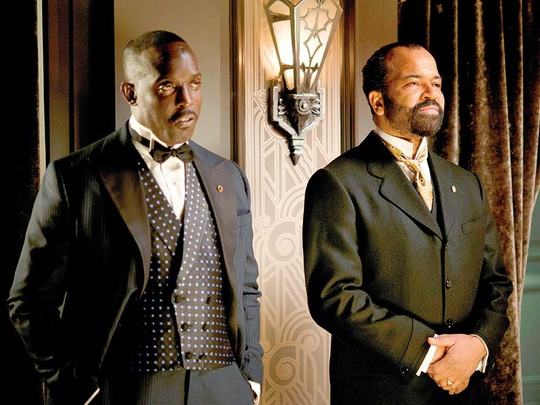

In the years since then, Williams, 50, has continued to draw inspiration for his characters from the world of Vanderveer, a housing complex now known as Flatbush Gardens, where he lived for much of his life. Time and again, his work has returned to the complicated intersection of race, masculinity, crime and institutional failure. After Omar, he was Chalky White, an Atlantic City bootlegger in Boardwalk Empire who reminded Williams of his father; then, in The Night Of, Freddy Knight, a Rikers Island inmate like his nephew Dominic Dupont; and Ken Jones, an activist in When We Rise, whose battle with HIV paralleled that of another nephew, who died.

“Vanderveer is 59 buildings, six floors high, with seven apartments on each level,” Williams said. “There are so many people here — beautiful and beautifully flawed people — and I want all of their stories to be told.”

REALITY BITES

It was a warm Friday afternoon in June, the 15th anniversary of the premiere of The Wire, and Williams was back in East Flatbush to celebrate with some friends. Though he lives in Williamsburg now, he goes back every few months to visit.

Darrel Wilds, 50, who grew up with Williams in Vanderveer says: “He’s [Mike] representing the people of this neighbourhood to the world.”

But even as he has worked to champion his community, Williams has often ended up falling victim to the perils he tried to elude there. Many of his roles have unearthed agonising memories and plunged him into a serious drug addiction that he grapples with to this day.

The Vanderveer of Williams’ childhood was often a landscape of drugs and violence. Born in 1966, Williams rarely envisioned a life beyond Brooklyn. His mother worked as a seamstress before opening a small day care centre she ran out of Vanderveer. His father was a gregarious but wayward man who battled health problems.

Starved of opportunities, many in the community took their cues from local gangsters, who exuded a swaggering masculinity that Williams contorted himself to realise.

As a boy, Williams was sexually molested, and the experience left him withdrawn and confused. He never spoke of the abuse back then, but his peers seized on his vulnerability and tormented him relentlessly. His life became a kind of delicate performance as he desperately tried to conform. Before long, he developed a drug problem, and by 19, he was cycling in and out of clinics. To finance his addiction, he tried his hand at carjacking and credit card fraud, though the schemes left him with little more than a thickening arrest record.

Alienated from his family and friends, he found a sense of belonging at the bars of downtown Manhattan in the 1980s and ‘90s. Williams relished the sheer liberty of carousing around a space unencumbered. Many weekends, he would dance until the early morning at clubs; his nimble moves even landed him some work as a part-time backup dancer.

Then one night at a bar in Queens, on the eve of his 25th birthday, he stepped outside to find a group of men jumping his friend. When he tried to intervene, one of the muggers pulled out a razor blade and sliced him across his face and neck. One gash went straight through his jugular.

The attack left an indelible mark: a scar trailing diagonally down his face, from the top of his forehead to the middle of his right cheek. It was impossible to ignore. And it radically transformed his image.

Soon enough, he was dancing in music videos and on tour alongside artists such as George Michael and Madonna, inevitably cast in the part of a street tough. His first substantial acting role came courtesy of no less an authority than Tupac Shakur, who tapped Williams to play his brother in the 1996 film Bullet. Three years later, he appeared as a drug dealer in Martin Scorsese’s Bringing Out the Dead. Then it was a brief cameo on The Sopranos. And finally, in 2002, The Wire.

His Omar character became the show’s icon, the subject of tribute art and academic dissertations. When Williams moved back into his apartment in Vanderveer after the first season, in 2002, the attention was intoxicating.

“There was just one small thing,” he said. “No one was calling me Mike. They were calling me Omar. That’s when the lines got blurred.”

HARSH TRUTH

Months removed from filming, Williams struggled to shake Omar’s grave psyche. Had he lost hold of his identity? Was he glorifying the ills of his community, or exposing their roots? He couldn’t divine the answers, so he turned to cocaine.

Williams made it through the show’s run with the support of a church community in Newark, New Jersey, but his drug dependency lingered as he continued to question the impact of his work. In spring 2008, just after The Wire ended, he was on a three-day-long bender when his mother brought him to a rally for Barack Obama in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Earlier during his campaign, Obama had declared The Wire the best show on television and Omar his favourite character. When the two men met privately after the event, Williams, lock-jawed and high on cocaine, could barely speak.

“Hearing my name come out of his mouth woke me up,” he said. “I realised that my work could actually make a difference.”

Williams resolved to continue pursuing powerful stories, no matter how agonising the demons they unleashed. Most immediately, he is completing a documentary to be released through Vice on HBO. The project intends to detail the dangers and inequities of the US criminal justice system, particularly the juvenile justice system.

In one scene, Williams visits a middle school in Newark, where he speaks with a seventh-grader named Mike. The boy had maintained a reticent facade during filming, but eventually opened up at Williams’ coaxing, telling the harrowing story of his mother’s death along with his father’s abuse. “I was abused, too, when I was younger,” Williams tells the boy. “And I did a lot of stupid stuff to hurt myself.”

As he ambled through East Flatbush that June day, flashbacks of past tribulations came to Williams in waves. Afternoon turned to evening, and everyone seemed to assemble on the handball courts to share a bottle of Hennessy.

“Man, why do you even stay coming out here?” a friend named Earl asked. “Why not Los Angeles?”

Williams laughed. It’s a question he gets a lot.

“We’ve been taught success means leaving the communities that made us, but this is the only place in the world where I feel free,” he said.