Joseph Kahn believes he’s contributing to the endangerment of Koreans.

Research has shown that South Korea has the lowest fertility rate in the world, at less than 1.1 births per woman. But Kahn isn’t married, and he doesn’t plan to have kids. He jokes that Koreans will soon be extinct.

“We’re literally the pandas of the human race,” he says. “You’re very lucky to be talking to me, because I’m a beautiful panda.”

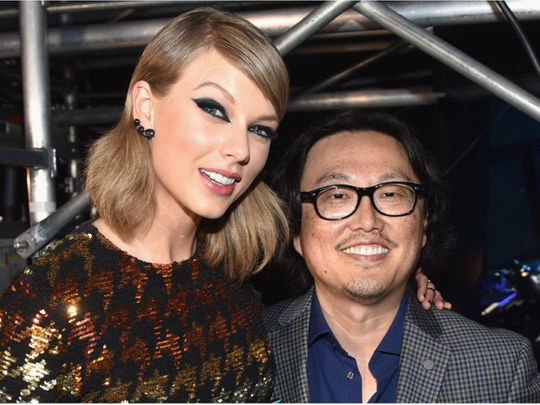

The comparison isn’t totally frivolous, as Kahn is unique in Hollywood. He’s the rare director who has achieved minor celebrity status not for his feature films, but for his persona and his short-form work, such as four music videos for Taylor Swift, including the action-packed, star-studded Bad Blood, which won the 2015 Video Music Award for Video of the Year. And in an industry that has been repeatedly called out for its lack of diversity, he’s a successful Korean American immigrant.

But most important to him is that, unlike many calculating, ultra-PR-conscious stars of modern Hollywood, Kahn, 43, keeps it real. His Twitter feed is a bastion of brutal honesty and shade that Hollywood blogs occasionally pick up on for one-off stories. Recently, for instance, his comments calling Kim Kardashian “one of the most untalented women in the world” throughout the controversy over whether Swift consented to her appearance in Kanye West’s Famous made headlines, and he ridiculed Kardashian’s dad’s support of O.J. Simpson during his murder trial.

If you look at Kahn’s Twitter account during the now-canonical Swift-centric firestorms (her feud with Nicki Minaj over VMA nominations; the backlash against the Kahn-directed Wildest Dreams video; the ongoing disagreement with Kim Kardashian and West), you might wonder if he’s a secret member of Taylor’s squad, given his unabashed defensiveness and admiration of her. In an interview, he says of their collaboration: “It was literally one of the first times I felt that someone actually spoke the language of filmmaking that I’ve been doing over the last 25 years.”

But more importantly to Kahn, he’s fed up with how the media covers celebrity news. “Our world is equating gossip with world news. That’s the world we live in now,” he says. Few outlets are focused on artistry, and Kahn can’t stand it — so he takes to Twitter to try to set the record straight.

For Kahn, it isn’t enough just to create films. He believes part of his art involves pointing out inconsistencies, half-truths and hypocrisies.

Race is one thorny topic Kahn loves to probe. His tweets on the topic of his Asian identity range from oddly empowering (“Of course I take criticism. I have Asian parents. Take your best shot. I’m Asian proofed.”) to potentially offensive (“I love my cast on #BODIED. Every single beautiful person. I would adopt all of them. Except Asians eat their pets. No bueno.”).

And yet, when writers criticised the video for Swift’s Wildest Dreams for romanticising the colonisation of Africa and not including many performers of colour, Kahn wrote in a statement that the “key creatives” who made the video were people of colour. Further, since the video follows an American film crew shooting in Africa during the early 20th century, Kahn and his team “collectively decided it would have been historically inaccurate to load the crew with more black actors as the video would have been accused of rewriting history.”

As a child, Kahn was painfully aware of his minority identity and how it would make him an outsider or, at best, an outlier for the rest of his life. After spending time in both Italy and Korea, where he was born, Kahn and his family moved to a white neighbourhood near Houston.

“Now, people think Asians are smart,” Kahn says. “In the ’80s, we were a third-world country. No one thought we were smart.”

He recalls being bullied by white kids, black kids and Hispanic kids alike. He spent most of his younger years alone, watching television and music videos.

The exclusion persisted even a decade later, as Kahn was trying to break into directing music videos. He remembers being rejected time and again by producers and artists because he wasn’t “cool” enough.

In the early ’90s, before hip hop became more mainstream, he worked mostly with such up-and-coming artists as Geto Boys and Ahmad who couldn’t afford a more expensive director. Later, he was recruited to help transform a then-unknown band of five into a “white Jodeci.” That group became the Backstreet Boys, and Kahn directed the video for Everybody (Backstreet’s Back).

Now, Kahn says that whenever he can, he tries to integrate performers of all colours and backgrounds into his videos (although Wildest Dreams is a notable exception). It isn’t so much a political act, he stipulates, as his instinct to bring together all types. “There’s nothing that makes me happier,” he says.

His third feature film, Bodied, which wrapped up at the end of July, exemplifies Kahn’s racial vision. Described as a “racial satire,” it’s about battle rap, a subculture that involves rappers hurling insults, many of which are race-based. But screenwriter Alex Larsen — also a battle rapper known as Kid Twist — believes that the genre is a positive force because it brings together a diverse array of rappers, including Larsen, a white guy from Toronto, where white liberals tend to congregate only among themselves.

“When these guys stop battling, we’re all actually friends with each other,” he says.

Unsurprisingly, Kahn says he prefers the honest — if occasionally offensive — rhetoric of battle rap over “casual racism” that pervades popular culture and that he’s faced throughout his life.