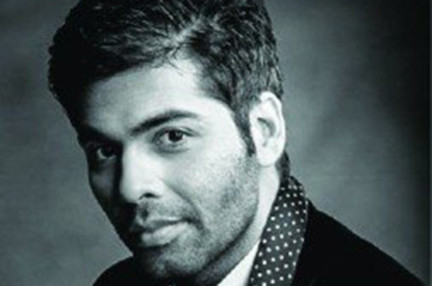

The much-anticipated memoir of filmmaker Karan Johar has been creating waves on social media after chapters describing his fallout with actress Kajol were leaked on Twitter.

But contrary to initial reports, An Unsuitable Boy is much more than just the narrative of a fallout.

Honest, decisive and compelling, it lays bare the other side of Bollywood’s pomp and gaiety.

It’s also brutally frank about Kajol. “I don’t have a relationship with Kajol any more. We have had a fallout. Something happened that disturbed me deeply which I will not talk about because it is something that I like to protect and I feel it would not be fair to her or to me. After two-and-a-half decades, Kajol and I don’t talk at all,” he writes.

Last year, Kajol’s husband Ajay Devgn went public with a recorded conversation with self-proclaimed film critic Kamaal R. Khan, who allegedly said he was paid Rs2.5 million (Dh134,476) by Johar to write favourably about the Ranbir Kapoor-Anushka Sharma starrer.

Devgn demanded an investigation into the matter and Kajol came out in her husband’s support by tweeting, “Shocked”.

Johar says her tweet was the final straw for him.

“Before the release of Ae Dil Hai Mushkil, there’s a lot that happened. Things were said, crazy accusations were made against me, that I had bribed someone to sabotage her husband’s film. I can’t even say that I was hurt or pained by it. I just wanted to blank it out.

“When she reacted to the whole situation, and put out a tweet saying, ‘Shocked!’, that’s when I knew it was completely over for me. The tweet validated the insanity, that she could believe I would bribe someone. I felt that’s it. It’s over. And she can never come back to my life. I don’t think she wants to either,” Johar writes in the book.

Kajol plaed the lead actress in Johar’s debut film, Kuch Kuch Hota Hai. They later went on to work in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham and My Name Is Khan. Johar also considered her his lucky charm with the actress making an appearance in most of his films.

Johar says he never had a problem with Kajol but he did not exactly share a good equation with her husband.

“The problem was actually never between her and me. It was between her husband and me, something which only she knows about, he knows about, and I know about. I want to keep it at that. I don’t really want to say what transpired. But I did feel that she needed to apologise for something she didn’t do.

“I wouldn’t want to give a piece of myself to her at all because she’s killed every bit of emotion I had for her for twenty-five years. I don’t think she deserves me. I feel nothing for her anymore,” he writes.

Not only does the filmmaker write extensively about his sexual orientation, the time when he lost his virginity and about his “two unrequited love situations”, the dark side of Bollywood — its insecurities and jealousies — also find sufficient mention.

Talking sex

Much has been said and anticipated about Johar’s sexual orientation in the past but he has somehow maintained a low profile on this, avoiding the topic on many occasions. It is for the first time that the filmmaker has talked at lengthen this topic.

Johar writes that he had his first sexual encounter at 26 but this is not something he is “proud” of.

Completely inexperienced sexually up to that point of time, he paid for sex in New York. “It was a nerve-racking experience for me,” Johar says in his memoir.

Johar also points out that, somehow, people equate being in the entertainment industry with having a lot of sex.

“But I don’t want that much. Actually I don’t care about it. People think that since I am travelling a lot, I am having a lot of sex. But it doesn’t happen that way. A boarding pass is not a pass for sex. I am not in love with anyone anymore,” the filmmaker writes.

There is a strong reason behind the importance that he gives to sex in this memoir. Johar, in his own words, “was very backward in this department” as a child.

“There was a big age-gap between me and my father, and no one else told me about these things. I had a very square group of friends: We were all very good girls and boys. We were the Gujarati bunch who would go for picnics. We were the most uncool, unaware and innocent lot,” he writes.

However, there are no full stops or ambiguity as one moves from sex to cinema, something Johar has been passionately involved in. The filmmaker feels that the new trait he has acquired is honesty, something which, according to him, he did not have in the last decade because he felt the need not to be honest in personal or professional situations.

“There was a time when I was very concerned about what other film-makers did... It was borderline jealousy, competition... I used to sometimes wish their films wouldn’t do as well as they did. I used to be troubled by Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s brilliance. I used to be affected that I couldn’t write a film like Raju Hirani,” Johar writes.

Another significant issue that find mentions is his feeling that he never gets credit for his work.

“I feel no matter what kind of films I do, I never get credit. It gets forgotten immediately afterwards. I am still associated with popcorn, frivolity, NRIs and rich people,” he writes.

One thing is clear, Johar is not delivering a sermon or projecting the faults of the film industry or offering advise on what to do and what not to do in Bollywood, he is rather telling a story — his intimate story.

Has the filmmaker been honest in his narrative? One cannot say for sure, but given the fact that most of those whom he writes about are still around, some as powerful in the film industry as this filmmaker himself, one would imagine so.

Despite the controversies that are already doing the rounds and those that may crop up in the days to come, this is a significant memoir, opening doors to the troubled minds of Bollywood.