At first, it feels like you are in a high-security enclave. High barricades bookend the infamous Herbertstrasse, sometimes called the “street of shame''.

Then, women perched comfortably on swivel chairs come into view, dressed in nothing but stockings and suspenders, looking out from narrow shop windows.

Some stick their necks out to lure passers-by to come in or to hurl invectives at tourists trying to cheekily snap a picture.

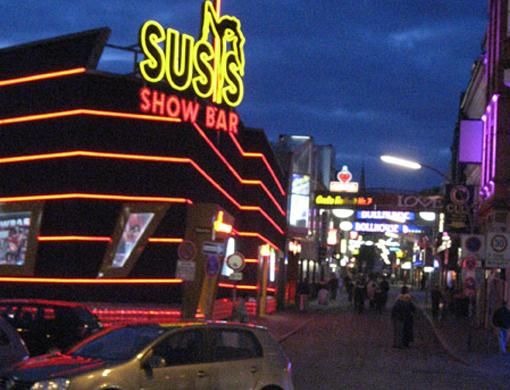

Well-known for its tacky sex shops, strip joints, bordellos and casinos, the Reeperbahn in Hamburg's St Pauli district is one of the world's oldest and most famous red light districts.

Once a favourite hangout for fatigued sailors from ships that berthed at Hamburg's famous port, it slowly began drawing hordes of tourists from all over the world.

But nowadays prostitution is gradually dying in the Reeperbahn — also known as “die sündige Meile'' in German or “the sinful mile'' — struggling to strike a balance between tradition and modernity.

The sex industry is in terminal decline as prostitution flourishes through more modern ways — mainly through the internet, a medium considered both discreet and safe.

On April 1, Hotel Luxor, the Reeperbahn's oldest brothel, located on a narrow side street called Grosse Freiheit, shut shop forever.

Waltraud Mehrer, a blond-haired, petite woman who was Luxor's madame for more than two decades, sighs at the economic realities that led her to close her business.

“It's a sad development,'' she says. “You just can't make enough money in the Reeperbahn anymore. Private call girl services and internet sex ate into our business.''

In the 1970s, when Luxor did brisk business, it remained open 24 hours. But in the months leading up to its closure, it barely stayed open for four nights a week.

Many other brothels face a similar predicament. Reeperbahn's famous, multi-storeyed Eros Centre brothel was once the biggest in Europe.

An Aids scare forced it to close in 1988, only to resume a few years later in a much smaller building. Today, its dank, neon-lit corridors invite customers to a host of East European and Russian girls.

The Reeperbahn is considered by many of Hamburg's denizens an inseparable part of the city's rich cultural identity.

In the early 1960s, before they became world famous, the Beatles performed in several clubs in this area. Stories of their on-stage antics still resonate from locals. (“On a dare, John Lennon played a song clad in his underwear and George Harrison played with a toilet seat around his neck.'')

In its heyday, St Pauli was home to more than 1,000 prostitutes. Today there are fewer than 500. It has become a hotbed of violent crime.

Lately there has been a surge in the number of teenage binge drinkers and an alarming rise in street crime because of pimp rivalries.

There are more than 200 incidents reported every month in David Wache, the local police station. Close to 50 per cent of the perpetrators are teenagers.

In a large trial in 2006, ten members of the Marek Gang, which controls brothels on and near the Reeperbahn, were charged with pimping.

The judge rejected the charge of forming a criminal gang and handed out suspended sentences: The men had started relationships with young women in local discotheques to recruit them to work in their brothels, and this is illegal if the women are under 21. Some men had also abused some of their women.

To curb violence, local authorities set up a host of surveillance cameras in the area in 2005 but crime still kept rising.

Last year the Hamburg senate imposed a comprehensive ban on weapons — including knives and, after 8pm, beer bottles — in the area. They are also mulling a blanket ban on alcohol consumption in the area, though that might severely impact business of the bars.

The Hamburg police has set up a special commission called “Rotlicht'' to tackle the growing crime. The main strategy to boost security is to increase the number of policemen stationed in David Wache.

In a massive crackdown, 80 policemen reportedly raided three prostitute houses in the Reeperbahn late in the night.

Fifty-one prostitutes operating without local authorisation were seized from brothels such as Night Life and Galerie.

“There will be more raids,'' warns Alexandra Klein, a dour-faced and stern officer from the Hamburg police who heads Rotlicht. “We intend to make life hard for any potential mischief-maker in the area.''

Local sex touts privately complain that the huge police presence is hindering the already-slack business.

“My business has gone down by three times,'' a local tout, who gives his name as Edward, says, grimacing, as Frankie Valie's Can't Take My Eyes Off Of You blasts from a table dance club close by.

Edward, who works as a middleman for a club called Table Dance Shop, located in the centre of St Pauli, says: “These are bad times.''

A steady decline in the number of tourists visiting the Reeperbahn is severely impacting business, he says.

He once was a flourishing middleman who supplied girls from Russia and Eastern Europe to various brothels in the Reeperbahn.

But now, with declining customers, his share of the commissions has also plummeted. “You shouldn't forget,'' he says, “if the brothels don't survive, no other business in the area will. They'll all be finished.''

It is a view that resonates well with Cornelius Littmann, a middle-aged businessman who owns a football club in Hamburg named after St Pauli — FC St Pauli.

Littmann also owns the Schmidt Theatre, a theatre group centrally located in the Reeperbahn. Littmann's businesses capitalise on the crowds coming to see the Reeperbahn every day and particularly on weekends.

He believes that every attempt should be made to staunch the terminal decline of the Reeperbahn.

“I don't think the Reeperbahn can ever totally die or disappear,'' he says, “largely because of its unique identity. Its stature might diminish, but it can't completely go away.''

“Tourists visit Hamburg not just for its seagulls,'' says Campbell Jeffereys, an Australian author and journalist, “but also for its bawdy red light district.''

Jeffereys has lived in the heart of the Reeperbahn, on a street called Hopfenstrasse, for the last four years. Leading up to his house, a seductively cavorting woman in leather boots invites you.

Living amid the sleaze hasn't been easy for Jeffereys. Visitors often leave lewd graffiti on the walls of his apartment block.He often encounters shady visitors outside the block.

Not to mention the noisy 4am brawls among pimps and drunken teenagers. Still, Jeffereys doesn't wish for the authorities to do away with the red light district, something that gives St Pauli a distinct character.

But this view doesn't resonate with all, not least with businessmen such as Andreas Fraatz, a real-estate magnate who owns the Empire State hotel, a tall, shiny and swanky glass building overlooking Hopfenstrasse.

The hotel began operations just six months ago. Fraatz is also the man behind a $400-million project that includes apartments for high-income earners. (Fraatz's office didn't respond to repeated requests for an interview).

Many in the area, including Malina Morsdorf, the owner of a café called Mother's Fine, blame him for the decline of the Reeperbahn.

“His vicious attempts to gentrify the place will ruin St Pauli,'' she warns. “He thinks of the prostitute houses as an eyesore.

He wants to convert this cultural hub into an upmarket destination for the rich.''

Fraatz is also blamed for the steadily rising rent in the area, which has led to the closure of some bars in Hopfenstrasse.

Call girls, who once occupied windows in the graffiti-plastered buildings on the street, too, mysteriously disappeared 18 months ago, locals say.

“If you take the sex out of the Reeperbahn,'' Jeffereys says, “you will take away the soul of the Reeperbahn.''

Anuj Chopra is an independent writer based in Bonn, Germany.