Netflix has been a hot button topic at the Cannes Film Festival. First, Spanish auteur Pedro Almodvar, the head of the festival jury, publicly advocated against eligibility for Netflix movies that won’t be in theatres to win the Palme d’Or. A couple days later, when Okja premiered, the very appearance of the Netflix logo at the start of the film prompted booing from the crowd. Bong Joon-Ho’s movie was one of two films distributed by the streaming giant in competition for the Palme d’Or; the other was Noah Baumbach’s The Meyerowitz Stories. (The winner is announced on Sunday.)

On this side of the pond, however, filmmaker David Michod was being much more diplomatic, even though his new movie, War Machine, is a Netflix original.

“Something will come out of this tussle and I hope whatever it is it’s satisfactory to everybody,” he said. “I don’t want anyone to lose that battle, you know what I mean?”

Sure. On one hand, seeing a movie in a theatre can be a magical, communal experience. But if the big studios are only putting money on blockbusters with the potential to play well overseas, many feel that Netflix could help the art form by bankrolling big-budget movies, with total disregard for ticket sales. Would War Machine — a $60 million (Dh220 million) military comedy that will only get a limited release in New York and LA — have even gotten made without Netflix’s help? It’s hard to imagine.

The movie, which is currently streaming, stars Brad Pitt as General Glen McMahon, the new guy in charge of cleaning up America’s mess in Afghanistan. The movie is a sharp satire but also heartbreakingly tragic at times. Pitt plays his character for laughs: He growls his lines, squints one eye and moves with the grace of a robot.

“We are here to build, to protect, to support the civilian population,” McMahon tells his underlings during what he clearly thinks is a rousing speech. “To that end, we must avoid killing it at all costs.”

The movie is a fictionalised take on the book The Operators, by the late journalist Michael Hastings, which chronicled General Stanley McChrystal’s war effort in 2009 and 2010. He was relieved of his post after Hastings published a profile of him in Rolling Stone that made the commander look, at best, insubordinate. The movie also gets into the difficulties of winning a war through counterinsurgency. Even with the comedic elements, this isn’t light stuff.

“We knew we had a movie that was challenging,” Michod said. “It’s dense with information, it’s a political quagmire. On one level it’s an unequivocal kind of antiwar film and yet there are characters in it trash-talking Obama.”

This is not the kind of movie that would make big money at the box office. Contemporary war movies rarely do, unless they’re in the simplistic good-versus-evil mold of American Sniper and Lone Survivor. The more nuanced or overtly political dramas, like Lions for Lambs, In the Valley of Elah, Rendition and Jarhead, couldn’t make back their budgets in domestic ticket sales. More recently, Shia LaBeouf’s Man Down made headlines when it grossed the equivalent of one ticket sale during its UK opening weekend (Granted, it only premiered in one theatre, but still.)

But Michod doesn’t have to worry about ticket sales now. That’s not part of Netflix’s business plan. The company has poured money into new programming to boost subscriptions; if a Netflix movie is released in theatres at all, it’s the bare minimum to be eligible for Academy Awards, which is why Beasts of No Nation got a limited run in 2015. And even then, Netflix does “day-and-date” releases, meaning the film will stream the same day, leaving little incentive for subscribers to go to the multiplex. This, understandably, has frustrated movie theatre owners. Filmmakers, too, have their concerns about making movies that can’t be seen in the immersive way only a theatre can provide.

And yet the list of directors who are working with Netflix is only getting longer and more impressive, with the legendary Martin Scorsese signing on with his highly anticipated next film, The Irishman. It’s easy to see the appeal of working with the company, which has a reputation for handing over money without much oversight.

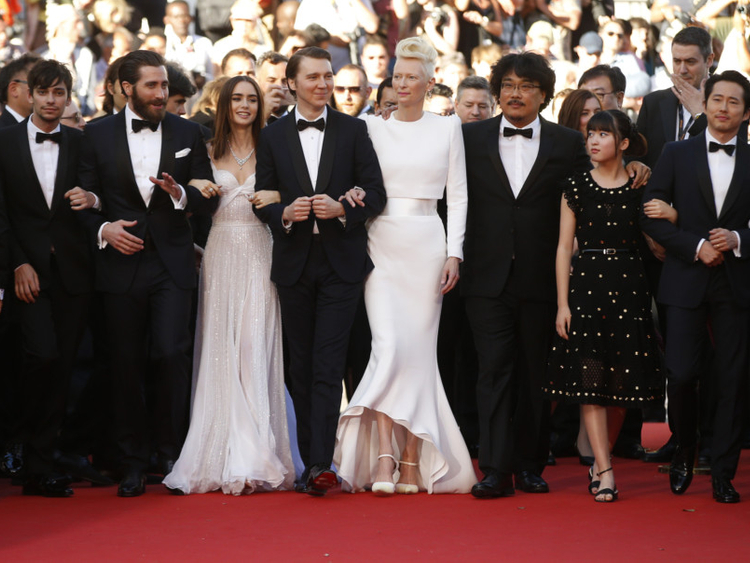

“Netflix guaranteed my complete freedom in terms of putting together my team and the final cut privilege, which only godlike filmmakers such as Spielberg get,” Okja filmmaker Bong-Joon Ho said during a news conference at Cannes.

Like Okja, which is heavy on the special effects, War Machine was never going to be a cheap movie to produce. During a Tokyo news conference while promoting the film, Pitt said that without Netflix, “if it did get made, it would have been at one-sixth of the budget.”

Michod thinks the company is simply filling a gaping hole that was left after independent studios and speciality divisions, such as Warner Independent and Paramount Vantage, closed up shop. The Australian writer-director gained international notice with the release of his 2010 thriller Animal Kingdom, but his big moment felt bittersweet.

“I felt like I’d arrived at totally the wrong time,” he said. “People weren’t making those movies that I had loved from the late ‘90s and early 2000s... but those were the movies I was meant to make.”