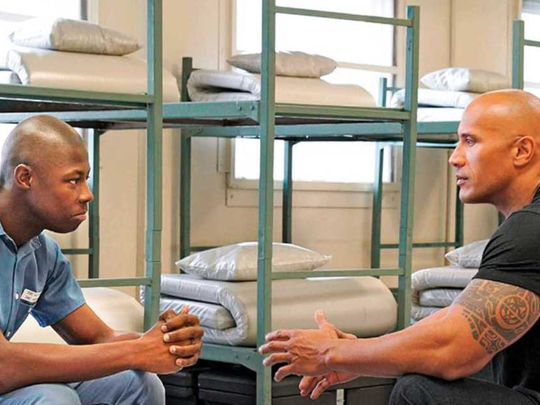

The celebrity host: Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson.

The challenge: 38 young convicted felons who must make it through four gruelling months in a boot camp rehabilitation programme or face prison sentences ranging from five years to life.

If HBO’s Rock and a Hard Place sounds more like a reality television competition than a documentary about the lives of young men at risk, that’s because it’s often hard to tell the difference.

With the Ballers and Fast and Furious franchise star as an executive producer, the hour-plus film directed by Jon Alpert and Matthew O’Neill takes place at the Miami-Dade County Corrections and Rehabilitation Boot Camp in Florida. Repeat offenders whose crimes range from armed robbery to carjacking to assault with a deadly weapon have been given the choice by a judge: incarceration or rehabilitation. They chose the latter, and that’s where we, the viewers, come in.

Rock and a Hard Place is reminiscent of the 1970s’ Scared Straight! documentary, in which young repeat offenders were subjected to terrifying lectures by hard-core convicts about the horrors of prison life in the hope that they would scare them away from a life of crime.

Here, the strategy involves correctional officers who act as drill sergeants and a live-on-campus programme in which military-style discipline is God. It’s tough love because, unlike a reality show, the real-life stakes are high. According to the documentary’s statistics, 75 per cent of ex-convicts return to a life of crime. The rate of boot camp graduates’ re-offending is reportedly a low 15 per cent.

Johnson appears briefly in the beginning of the film to address the “cadets,” all younger than 24, as they’re being processed into the programme.

Standing in rows, with freshly shaven heads and grim expressions, they listen as Johnson tells them he too began a life of crime as a teen. He knows what it’s like to be them.

“You don’t feel like it right now, but you’re lucky. You’re lucky you got another shot. Don’t [mess] this thing up.”

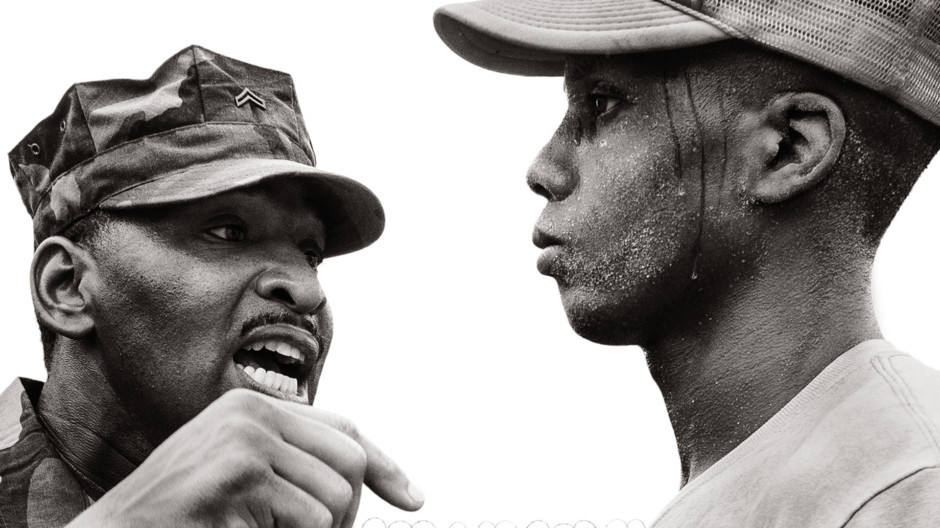

Then it’s time for 16 weeks in boot camp — and for viewers to put in the earplugs. Officers in army fatigues scream cadets out of bed each morning, yell them to breakfast, shout them through marching drills, berate them as they make their beds. The cadets must yell too when answering their superiors: “Yes, sir!” “No, sir.”

The film shows the provocation, humiliation and occasional praise used by correctional officers to build character in the young men. Quieter moments of counselling and classroom instruction are also shown here as cadets attend classes to deal with issues like drug abuse and to complete their high school education.

The intentions of the filmmakers are clearly noble, but the documentary is often so focused on the rigours of the programme that it fails to go deeper to show if and how these methods change the cadets and how that change might benefit them on the outside.

A cadet appears to have the same question in an anger management class, where the thinning group is being taught coping skills.

“Once you start gritting your teeth, that’s your warning sign,” says the counsellor. “Do not ignore your yellow light. This is your ticket to not coming back here.”

The cadet points out that they’re in a controlled environment: “The stuff you learn in this programme, most people who get out, I think they ain’t gonna be able to cope.”

“This is a form of rehabilitation and punishment,” she replies.

“I understand that,” counters the cadet respectfully. “But how long can you just keep saying cope with it, cope with it?”

“You cope with it until you get out of here. Cope with it.”

Watching these men struggle on camera to be “better,” without a more in-depth explanation of what that really means, feels exploitative.

In one scene, an officer berates a cadet for not speaking English: “No speak English?” she mocks. The documentary never shows if he is or isn’t taught English in the programme, but it does take the time to show him humiliated again by officers.

“If you don’t understand,” says one, “you will end up in prison and never see your mum again!”

He looks utterly confused. The officers then say something that sounds like “Get out of here, failure. Have a nice day.”

The usually stoic cadet heads out of their sight, then breaks down and sobs. What should be a breakthrough moment is instead just sad and cruel.

The few times we do get to see cadets outside of drills, lessons and routines are some of the most illuminating.

In a rare moment of casual conversation, an officer asks a cadet what he wants to do when he’s out. Go to “culinary school,” he answers.

“Where you want to work?” the counsellor asks.

“IHOP or Denny’s?” he says sheepishly.

“Don’t sell yourself short,” she says “We got Houston’s, P.F. Chang’s, Benihana.”

In another scene shot just after they receive letters from the outside, a young man sits on his bunk and carefully reads his letter aloud, tracking each word with his finger. He gets to the end: “‘Love, Dad.’ See, even though I’m in jail, people still love me.”

You’re rooting for these young men. But by the end, when the Rock returns to see them beaming and proud in front of their families and the judges who gave them a second chance, it’s like the tidy neat ending of a reality show.

The real challenge lies ahead of them, and as viewers, we have no idea if they’re ready.