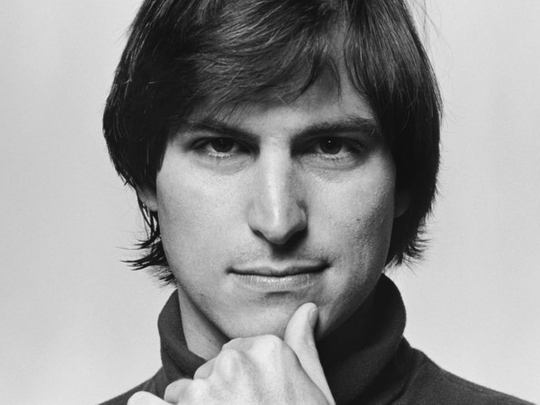

As the man who enabled phones to play music and laptops to sing, Steve Jobs was beloved in ways few modern executives have been. When the Apple co-founder died in October 2011, admirers around the world were so moved they gathered in tearful vigil and created a range of online and real-world tributes.

The documentary-maker Alex Gibney witnessed that sight. But rather than join the mourners, he had a different reaction: He asked why one stranger’s death prompted such an outpouring of emotion.

“Why do we idolise Steve Jobs? He didn’t write code, he wasn’t an engineer, and it certainly wasn’t simply the fact that he made a lot of money,” said Gibney, explaining both his personal feelings from the time and his motivations to explore the subject cinematically.

“I didn’t make this film because I said ‘let’s look at Steve Jobs’ dark side,’” he continued. “It was ‘let’s try to understand something very simple: Where did all this public grief come from?’”

The film is Gibney’s Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine and it kicks off a mini-season of Apple on US movie screens, with Steve Jobs, Danny Boyle’s dramatisation of key moments in the tech magnate’s life starring Michael Fassbender, coming to theatres a month later.

Though Gibney may not have consciously set out to expose his subject’s unsavory side, the question “what made Jobs so embraced by strangers?” leads him inevitably to “what made Jobs so polarising to those who knew him well?”

As Gibney unsparingly shows, the Apple visionary transformed lives with his relentless commitment to a future filled with cool, populist technology. He also made a lot of individual lives difficult with that relentlessness. (It is a subject, incidentally, that will seem especially timely in light of the furore over Amazon’s treatment of its employees.)

The engineer who helped create the Mac, Bob Belleville, can be seen breaking down crying in the movie as he described the toll it took on his marriage and other aspects of his life. Jobs’ daughter, Lisa Brennan-Jobs, describes a father remote and lacking in generosity. Jobs’ reaction to a tech blog’s reportage on a new Apple product, meanwhile, is depicted as a fierce overreaction.

“High-octane individuals like Jobs are not necessarily great people,” Gibney said. “But as a society we seem to have made a compact that if they do great things we should let them off the hook. And that doesn’t really seem like a good idea.”

Gibney was in his office overlooking the Hudson. The director, who won an Oscar with his 2007 US torture-centric documentary about Iraq, Taxi to the Dark Side, was surrounded by about a dozen workers staring intently at their screens. It was a fitting spectre for a man who has cranked out an eclectic mix of in-depth documentaries the way most people whip up breakfast foods: the wide breadth of the river on one side, staffers burrowing into the nitty-gritty on the other. Some of the screens he and others pored over were, what else, of the Apple variety.

Unexpected angles

With this film, Gibney is again taking on a much-covered news subject and finding unexpected angles, as he did in the recent Scientology investigation Going Clear, the WikiLeaks movie We Steal Secrets, the church-scandal documentary Mea Maxima Culpa, the Eliot Spitzer exploration Client 9, and the Lance Armstrong pic The Armstrong Lie, in which he found himself forced into a similar shift in his thinking about an “icon,” this time well into production. All of these films are essential, forensic investigations into subjects we thought we knew.

“I’m drawn to these public stories that I think have been inadequately handled,” said Gibney, whose vocal manner might be described as thoughtfully declarative. “People make up their minds so quickly on them, because they’re covered so quickly. I think it’s important to go back.”

Gibney has been heading in a lot of directions lately. At 61, he has the energy and prolific streak of a director half his age, tackling exhaustive topics in a short period of time. Clear premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January and then played on HBO several months later. Jobs debuted at SXSW in between the two. They both followed Armstrong, which debuted just 16 months before Jobs — and the same year as We Steal Secrets. He has also found time in the past few years to make movies about the musicians Fela Kuti and James Brown and a few others too.

“You know that kid in college who could study really fast and still get an A?” said Sheila Nevins, the HBO documentary tsar who has made many movies with the filmmaker, including Going Clear. “That’s Alex.”

Gibney made his first film 25 years ago — The Ruling Classroom, about a school experiment in self-governance that went terribly awry. Although he followed it up with works about the likes of Jimi Hendrix and the sexual revolution, he hit his stride in 2005 with the Enron movie The Smartest Guys in the Room, an abuse-of-power story that helped kick off his current streak of newsy exposes.

Nevins described him as a cool customer in the face of controversy, a factor that came in handy when the Church of Scientology unleashed its publicity firepower in the direction of the filmmakers. That both Jobs and Clear are fundamentally about peeking under the hood of institutions with cultish followings is not lost on Gibney.

Code of silence

Apple’s reaction has been more muted than that of the church. Following a Silicon Valley code of silence, the tech firm made no major statements, although it cast a long shadow during production; Gibney had to go to some lengths to secure the participation of credible critics who knew Jobs well.

That the executive could be a difficult person will not be news to those familiar with coverage of Apple or who read Walter Isaacson’s biography shortly after Jobs died. But the film goes further than the book in isolating some of the ways Jobs could be unstinting while, as a visual piece, offering a more concentrated punch to the hagiographic myth.

Among the more cringeworthy stories are those of Lisa Brennan-Jobs’ mother, Chrisann Brennan, as she describes Jobs’ reaction to her pregnancy — basically, to demonstrate abject anger to her and others in the room. In Steve Jobs, Gibney asks whether the correlation between genius and difficulty is not only strong but unavoidable.

The director’s starting point — about what made Jobs so liked — does not yield a singular conclusion. But the director does see Jobs’ power as coming from what he represented as much as who he was.

“Steve Jobs was a marriage broker between us and these devices; he understood how to create a connection between us and machines,” Gibney said. “And he was a performer, an evangelist, really. When you view it that way, it makes sense that there would be an outpouring of grief, or that some would say, as [former Oracle CEO] Larry Ellison did, that you shouldn’t focus on anything bad because it’s important to have heroes like Steve Jobs.”

Gibney said he realised that that his smash-the-idols sensibility may not be commercially palatable. Mainstream documentary audiences tend to want investigations of known evils or a confirmation of decided heroes. The idea of finding that our role models (Jobs) are neither as virtuous as we thought nor our villains (Spitzer) as culpable could be unsettling, to say the least.

But Gibney wants to keep making films like this, he says, because he believes they could be a corrective to a culture that, despite all the media — and perhaps because of all the social media — can be unwilling to see subjects in shades of grey.

“Our media climate is often all good or all bad, all binary. It’s this point-counterpoint view we have of the world and certainly of public figures. It seems so misguided. If we think this way we’re either going to be radically misinformed or disappointed.

“I guess that I’m swimming upstream. But you’d hope people would reckon with these ideas. Shouldn’t we begin making more distinctions?”