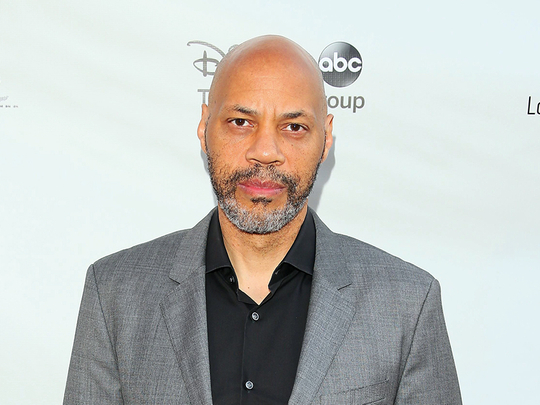

John Ridley’s eyes narrow as he stands on an undistinguished stretch of Foothill Boulevard in Lake View Terrace, watching intently as traffic whizzes by condo developments near the 210 Freeway and Osborne Street.

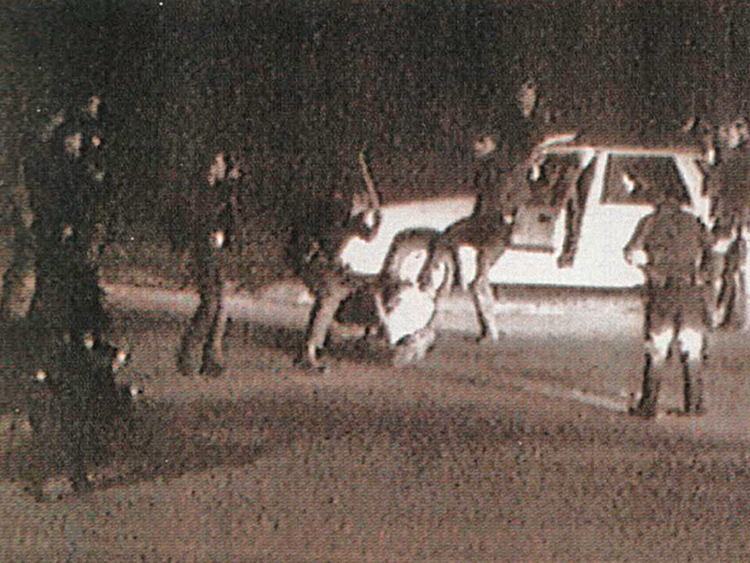

The Oscar-winning screenwriter (12 Years a Slave) and creator of racially charged fare such as ABC’s American Crime and Showtime’s just-launched Guerrilla is trying to pinpoint the exact spot where African American motorist Rodney King was brutally beaten in 1991 by four white Los Angeles Police Department officers. Their acquittal in a 1992 jury trial touched off riots that held the city in a terrorised grip for nearly a week.

Twenty-five years later, that uprising and its aftermath still rank as one of the most tumultuous — and shameful — chapters in Los Angeles history.

“There’s no plaque, no marker, nothing to mark that spot,” says Ridley as he scans the surroundings. “History happened here.” Although the filmmaker, who is rarely at a loss for words, keeps talking, he struggles to articulate his feelings about the absence of an indicator for the location.

He finally finds the word that summarises his thoughts: “It’s just... surreal.”

Rather than words, Ridley is letting his art express his emotions about the anniversary. Teaming up with ABC News’ Lincoln Square Productions, he has directed his first documentary, Let It Fall: LA 1982-1992, a wide-ranging — and frequently heartbreaking — look not only at the flareup, but at violent incidents in the decade preceding the riots, and the aftermath in the ensuing years.

The nearly two-hour film, the most high-profile of a flurry of LA riots-related documentaries airing this month on broadcast and cable, premiered in US theatres on April 21. A shorter version airs on ABC on April 28.

On previous anniversaries, projects or studies of the turmoil have been scarce as filmmakers struggled to get a narrative grasp on the epic scale of the events, which involved numerous communities and various cultural groups.

“I understand, as someone who loves history, how much history is not told or taught or seen as having value if it’s not heroic or neatly dispensed,” Ridley says, dining on Ethiopian food recently at a cafe a short distance from where King was beaten. He notes the magnitude of the uprisings, which resulted in more than $1 billion (Dh3.7 billion) in damage, more than 50 deaths and the destruction of 862 buildings. Some neighbourhoods still bear signs of the wreckage.

But he contends he is not concerned about the swarm of projects focusing on the same event: “From what I know of these documentaries, they all take different approaches. We’re not telling the story in the same way.”

Let It Fall shows the familiar camcorder video of the beating taken by plumber George Holliday, and news footage of the mayhem that erupted in South-Central Los Angeles following the verdict, including the vicious assault on white truck driver Reginald Denny.

But Let It Fall offers more perspective — both personal and professional — with new interviews from those directly and indirectly involved, including family members of victims, attorneys and police officers.

Asked what affected him most about making the project, Ridley doesn’t hesitate.

“It’s the immediacy of it all,” he says. “To sit three to five feet away from individuals, and they are still so much in that moment. Time hasn’t passed for them. There were things they can’t let go of, that they will never forget. To see strong people lost in emotion, and over things that are interconnected. These people don’t know each other, aren’t related to each other, but these series of events still uniformly impact them.”

The documentary caps what has been a whirlwind period for Ridley. He followed up his 2014 Oscar win for adapted screenplay with a deluge of provocative and insightful projects that have focused on race, class struggle and other topical issues including his Guerrilla and American Crime, currently in its third season.

Consequences

Jeanmarie Condon, an executive producer of Let It Fall, thinks it will resonate with viewers given the current political climate.

“At a time when some of the issues we deal with on the project are very much on people’s minds, it’s good to look back with wisdom and insight to what people were dealing with at that time,” Condon said. “I hope viewers get a sense that history doesn’t come about because of a grand plan. It’s human beings making very personal decisions, ones that are made in the moment, which have consequences.”

Ridley, who had just moved from New York to Los Angeles shortly before the riots broke out, has his own throat-clenching recollections of that period.

“I was living in the Fairfax area at the time,” he says. “That first night, I remember thinking, ‘This is bad, but something will contain this, the citizenry or police.’ But it was clear that there was a sense that people were no longer going to treat other people with compassion, and that the police were either unwilling or unable to restore order.”

Ridley and his associates wanted to tell the saga from several perspectives and even reached out to the four officers involved in the beating. All declined to participate.

“For me, it was important not to exonerate or indict people, but to create a space where they could feel comfortable to tell their stories the way they wanted to,” says Ridley.

He adds, “It was also important to show that for at least 10 years, people tried to call attention to the issues, tried to engage about what was happening between police and communities. If one thing could have happened differently, could it have changed things? Maybe. Maybe not. But the Rodney King riot did not start with Rodney King, and it didn’t end with Reginald Denny.”

The genesis for Let It Fall came about 10 years ago when writer-director Spike Lee contacted Ridley about writing a film about the riot that would be directed by Lee and produced by Imagine Entertainment’s Brian Grazer and Ron Howard.

“Even back then, there were all these stories that people associate with what we call the riot, but for me, it was an uprising,” he says. “That’s how I wanted to tell it. There wasn’t a main protagonist or antagonist. There were people who did very, very good things, but they were not action heroes. They didn’t have the typical narrative of a heroes’ journey. They were just at the right or wrong place at the right or wrong time.”

Although he turned in a first draft that he felt “came in very well,” questions about the budget and whether the film would make money surfaced. “You have this film with no hero, no heroic drive and, like much of my work, doesn’t end on an upbeat note.” Other factors including the economy and changing attitudes in Hollywood contributed to stalling the project.

After he was approached by Lincoln Square executives, “They wanted something that wouldn’t seem like a news documentary, a dry excavation of history. They didn’t know that I had been trying to put this narrative together and was familiar with all these stories and individuals who were involved.”

Ridley proposed constructing the project using an approach similar to American Crime, which allows for multilayered storytelling. A planned one-hour documentary gradually expanded when Ridley persuaded the network that the epic scale of the story needed more space to give it justice. He credited ABC for giving him the space to tell a more rounded account.

He hopes that Let It Fall will teach valuable lessons that might provide more scrutiny of volatile political and racial issues before they reach a breaking point: “If we wait for an outsized event, that’s when it becomes problematic.”