For the first decade of this century, Henry Cavill occupied the least coveted role in movies: Hollywood’s nearly man. He had lost out on a run of high-profile parts, including Cedric in Harry Potter and Edward in Twilight (both of which went to Robert Pattinson). In the search for a new James Bond, it came down to him and Daniel Craig.

Add to that the collapse of a Superman reboot in which he had been cast as the lead and you have an actor whose name was at risk of becoming a jinx.

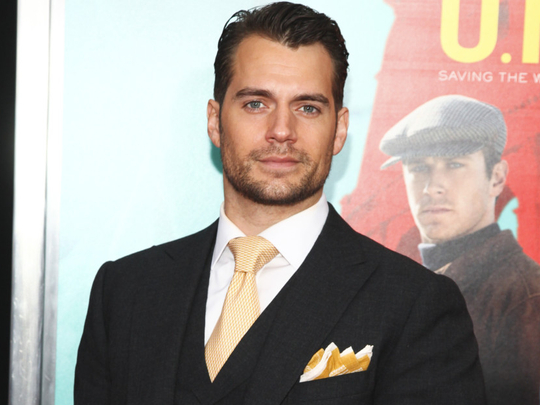

The 32-year-old Brit who sits before me in a minimalist hotel room in a pale blue shirt and black trousers is in a very different position. Two years ago, he finally got to play Superman in the alternately thoughtful and cacophonous Man of Steel. With Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice opening next spring, starring Ben Affleck as Batman, and assorted Justice League spin-offs looming, the red cape is his for at least the next five years. His name is even being linked to Bond again as Craig’s spell nears its end.

For now, Cavill is busy promoting a more frivolous sort of spy thriller: The Man from U.N.C.L.E., which turns the wacky 1960s TV series into a crash-bang-wallop action movie without jettisoning its small-screen silliness. The director is Guy Ritchie, the tone risque and metrosexual. Despite the cold war backdrop and the snazzy threads, this stylised romp bears as much resemblance to the real 1960s as The Flintstones did to the stone age.

“Guy was always telling us, ‘No one’s too cool, no one’s too funny, no one’s too stupid,’” he says. His square, striking face is dusted with stubble, his black hair meticulously gelled in to place. “It’s got that lovely thing of people seeming to be very sharp, then suddenly falling through a doorway. It makes larger-than-life characters human.”

The film might be crushingly insincere without the grudging rapport between its stars. Cavill, as the CIA agent Napoleon Solo, keeps his cool even when the back of his car is being torn apart by an unseemly brute; Armie Hammer playing his KGB counterpart Illya Kuryakin.

The Man from U.N.C.L.E. is expensive-looking fluff, but I wonder what it’s for: is it just escapism, or is something deeper going on? He thinks for a while. “I wouldn’t say it’s ‘just’ anything,” he says, bristling a little. “As an actor, I don’t go out looking for a message. But I believe anyone can take what they want from it. It’s set in a time of potential nuclear apocalypse and asking how that would feel.” He talks faster now, hitting his stride. “The 1960s were, apparently, awesome. So, if you’re sitting around now being a misery-guts because you’re having a bad day — well, what if it were the 1960s and the world could actually end and you couldn’t say goodbye to your wife and kids? That’s the lesson I take from the film.”

His manner is so ingenuous that you have to remind yourself he’s a box-office star, not the winner of a competition to be A Famous Actor. This can make him an easy target. (On YouTube, there’s a video interview in which Cavill’s highly considered answers to Superman-themed questions are mocked after the fact by Radio 1’s Nick Grimshaw and his cronies.) But the air of gratitude with which the actor regards his work is one of his most likable qualities. He took a long time to get where he is, graduating from TV walk-ons to major roles such as Charles Brandon, who was naked wherever possible in three series of The Tudors. He amassed bits and pieces of film work: he was a supporting hunk in Woody Allen’s Whatever Works, and a leading one in Immortals. His persistence paid off. Why affect nonchalance about that? He has his own production company now, which he co-founded with one of his four brothers, but if he’s ambitious he doesn’t let it show. He would be content, he says, to play Napoleon Solo “year after year”. The same goes for Superman. “It’s a wonderful role. There’s a huge potential there for complex storytelling, and I’m looking forward to exploring those avenues. Come on, it’s Superman! You can’t be pissed off at the idea of playing Superman for the rest of your life.”

He mimics a grumpypants actor: “’Oh sorry, I’m just the grandaddy of all superheroes. It’s such a pain.’”

Cavill’s Superman is the most troubled of any that has yet been seen — a hero forced to hide his light under a bushel, an immortal plagued by survivor’s guilt. “He’s a complex dude,” he agrees. “People think Kryptonite can beat him. No. The only thing that can really beat Superman is Superman. His own noggin messing with him. His own moral choices. When you have that to start with, the storytelling can really delve into something rich.”

Cavill grew up in Jersey but was sent at the age of 13 to the £30,000(D172,000)-a-year boarding school Stowe, from where he called his mother tearfully every day for the first two years. He’s used to money — his father is a stockbroker — and is in no mood to pretend he doesn’t like it. “There are some actors out there who are all, ‘Hey, I live in a cardboard box and I’ll perform on that cardboard box if I have to.’ That’s pretty much bullshit. Acting pays well. And anyone who says they don’t like money is being ridiculous. You shouldn’t be ruled by it, but money is lovely. Nice things are lovely.”

His honesty is refreshing. This speech, though, perhaps hints at one element missing so far from his screen acting. Anyone looking at Cavill’s work can see the skill, the nuance, the enthusiasm — but perhaps not always the passion. I wonder if he remembers feeling compelled to be an actor. “Where do our passions come from? That’s the real question. And why do they come from that place? Are we born with them or do we develop them from the reactions they get the first time we display them? When adults told me after my first school play that I was good, is that when I wanted to do it? It so happens that I like storytelling. But maybe that’s why I like it.” He laughs. “I’m getting a bit mind-[expletive] here.”

Self-critical

Cavill has spoken in the past about being bullied by schoolmates who considered him overweight. Acting provided a refuge from that: he could become other people, hide behind roles. He’s reluctant to pick over the subject again — he believes it has become a big story because of the irony of a bullied child growing up to play Superman. But, for all that he insists he doesn’t hate his tormentors, the taunts have stayed with him. Even once he became an adult, he would refuse to believe girlfriends who reassured him that his weight was fine. “I’m very self-critical and I use that to motivate myself. If I look in the mirror, I might say, ‘You’re looking good!’ Other days, like today, because I’m off-season and haven’t been training, I’ll say, ‘Look at you, you fat [expletive].’” I wince at that, and not only because the man sitting before me is in perfect physical shape. “I tell myself, ‘Mate, you’re a mess. If you were to meet a bird out in a bar and bring her home, she’s expecting Superman. This is not Superman and she’s going to be mega-disappointed.’”

Earlier on, he had argued that there wasn’t a downside to playing the character. It didn’t affect whether or not he would be seen getting hammered in public, he said. “‘Don’t make a [expetive] out of yourself’ is a good rule, whoever you are. Besides, it’s a character. If someone comes up and asks if I’m Superman, I say, ‘Sometimes. Not today, though, because I’ve got a pint in my hand. Also, I’m British.’”

And it wouldn’t harm his career if he were photographed going to see a Marvel film . “I love the Marvel movies. I just happen to like mine more.”

Now, though, he admits it isn’t always a breeze. “There’s a blessing in being Superman. You get more attention. But there’s also a curse, which is that you’d better [expletive] look like Superman any time you need to get your kit off.” It’s not only potential partners whose opinions he worries about. “You have your dark moments when you go on the internet forums,” he shrugs. “You’re peeking behind the curtain. You wonder, ‘What are people saying about me? Oh, that’s nice. Oh, how lovely.’ But then you find one that isn’t. One that says you’re only in a relationship to raise your profile, or to prove you’re not gay. You think, ‘Why are they being so nasty?’ Then you start shaping your behaviour around the comments, and that’s not OK. That’s not healthy.”

The narrative about the boy who grew up to vanquish his bullies doesn’t seem so neat or comforting any more. The bullies are still out there, but now they’re sitting at their computer keyboards, hiding behind usernames. He gives a helpless sigh. “It’s weird, because there’s no accountability. Someone can quite happily write a diatribe about how much of a [expletive] I am. But if they met me in real life, I know what they’d probably say.” Cue inane grin. “‘Can I have a picture with you?’”

The Man from U.N.C.L.E. is out on Thursday.