The Voice. Ol’ Blue Eyes. The Chairman of the Board.

All of Frank Sinatra’s nicknames speak to the sense of authority that made him one of the greatest entertainers of the 20th century. But in a 1971 concert at the Ahmanson Theatre in Los Angeles — a show billed as his farewell after a string of coolly received albums — it wasn’t Sinatra’s power that struck filmmaker Alex Gibney.

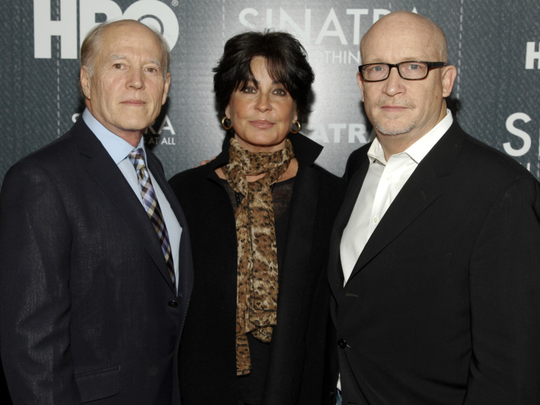

“This was a moment when the culture had passed him by,” said Gibney, known for his documentaries on James Brown and Fela Kuti as well as for HBO’s much-discussed Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief.

“It’s his big concert, and who does he invite? Henry Kissinger and Spiro Agnew,” Gibney went on. “He doesn’t invite John Lennon, you know what I mean? That’s where the culture was in 71, and he was no longer ahead of it in the way he often was in the past. I think that weighed very heavily on him.”

Four decades later, Gibney has used rarely seen footage from that Ahmanson gig in Sinatra: All or Nothing at All, a two-part HBO documentary set to premiere Sunday night at 8 in the US.

Charting the singer’s legendary determination to stay on top, the film takes each of the 11 songs Sinatra sang that night as the basis for a chapter in his complicated life — from his scrappy childhood in Hoboken, New Jersey, to his initial ascent as an early-1940s teen idol and on to the series of flame-outs and comebacks that would define his career over the next half-century.

“When Alex examines a subject, whether it’s a person or something like Scientology, he delves really deeply into it,” said Frank Marshall, the veteran producer who drafted Gibney to direct the film after they’d worked together on 2013’s The Armstrong Lie, about disgraced cyclist Lance Armstrong. “Sinatra’s life wasn’t one long stream of triumphs, and Alex was interested in how he got to where he was.”

The project began about five years ago, Marshall said, with interest from the Sinatra family in a documentary that would be completed in time to mark the 100th anniversary of the singer’s birth in 1915. (Sinatra died in 1998 at age 82.) Marshall knew the Sinatras through his father, Jack Marshall, a composer and guitarist who’d played on several Sinatra sessions in the 1950s.

That relationship ensured access to a trove of valuable material, including the film from the Ahmanson, which Gibney said had been languishing at Sinatra’s older daughter Nancy’s home. Grainy and apparently hand-held, the footage — with performances of Angel Eyes, That’s Life and I’ve Got You Under My Skin — provides an unusually intimate view of an artist we’re more accustomed to encountering in the “glitzy, but canned way” he was presented in numerous network television specials, said the director.

“I think the idea was, ‘Oh my God, he’s retiring — we better photograph this,’” Gibney said. (As always, the retirement didn’t stick.) “So the crew was kind of hastily assembled.” With a laugh, he added that the assistant editor, responsible for making sure the camera lens was free of debris, should’ve gone back to film school.

“But who cares if it’s of poor quality? It has such a vibe.”

All or Nothing at All also excerpts a remarkably candid lecture Sinatra gave at Yale University in 1986 as well as audio from various conversations the singer recorded at home while auditioning potential collaborators for an autobiography.

Forgoing the typical talking-head approach, Gibney weaves these elements together using voice-over narration from people close to Sinatra, including his children and ex-wives, and peers such as Tony Bennett. The result is an experience more immersive than many music documentaries, which the director said was his goal for a film he sees as “the story of America.”

“I wanted to think about Sinatra not just as the guy who had a lot of great songs but as The Great Gatsby,” he said.

Michael Lombardo, HBO’s president of programming, went further, describing All or Nothing at All as a tale of opportunity and ambition that couldn’t happen today. “It captures a moment,” he said, “when Americans truly believed the sky was the limit.”

That noble characterisation probably sits well with the Sinatra estate, which is using the singer’s centennial to roll out plenty of fresh product: repackaged collections of music, a stage production in London — even a branded whiskey from Jack Daniel’s.

Yet All or Nothing at All doesn’t skip over the less savoury aspects of Sinatra’s story, including his harsh treatment of women and his increasingly desperate attempts late in his career to adapt to the changing times. In one excruciating scene from a late-60s TV special, we see Sinatra do his best to hang with the trippy soul singers of the 5th Dimension.

No stranger to embarrassing evidence, Gibney said he insisted on creative and editorial control over the film, which he said the family allowed him. But he acknowledged that they’d “definitely” had disagreements, some over the question of Sinatra’s continued relevance.

If the singer eventually lost his grip on pop, though, Gibney thinks he persists today because of the emotion and passion in his best music, particularly the ballads.

“In the film Sinatra’s son quotes Charlton Heston as saying that his songs were like three-minute movies, and I think that’s dead-on,” the director said. “He was really a storyteller in song.”

Lombardo agreed, saying the way Sinatra sang at the height of his powers “changed popular music,” creating a demand for personality still being met by today’s stars. Gibney’s film, he said, makes that clear even to viewers too young to have witnessed Sinatra’s rise or his fall.

“That’s why we put it on Sunday night,” he said, meaning the most coveted — and youth-attuned — slot on HBO’s schedule. “I think this film forces you to hear what he did.”