There is something of the recluse about Alex Garland, even though — objectively — he is prolific, even ubiquitous, if you know where to look. His output since he wrote The Beach in the mid-90s has encompassed another novel, a novella, a handful of film screenplays and shifts on a couple of video games.

He has just completed his directorial debut, a sci-fi thriller called Ex Machina. He hasn’t gone anywhere, he’s hidden in plain sight, and yet it’s still a modest surprise that the 44-year-old is sitting opposite me, in the bar of London’s Soho hotel, pretty well unchanged from his dashing, two-decades-old author photograph.

If Garland seems elusive, it is not entirely my imagination. He has admitted that he was freaked out by the success of The Beach, which was published in 1996, when he was 26, and was reprinted 25 times in a one-year period before being made into a film directed by Danny Boyle, starring Leonardo DiCaprio.

The tale of a group of young European and American travellers who set up an idyllic community on a remote island in Thailand, it was a zeitgeist book, so perfectly pitched and executed that at the time it was almost impossible to find anyone of sixth-form or university age and beyond who hadn’t read it.

“What happened to that book was genuinely a surprise and it was a surprise to everybody,” says Garland now. “What really happened is it came out, it did all right, it got some good reviews, it got some bad reviews. Then some months after it came out, I started hearing, because I was a big backpacker, about people in Thailand reading it and passing it among themselves. This is the pre-internet period; it was a proper word-of-mouth thing.”

At what point did Garland start feeling uncomfortable with its popularity?

“Immediately,” he replies, shifting in his seat. “I never felt comfortable with it.”

Garland has by no means allowed The Beach to define his career — his strike rate in every genre he’s entered is enviable — but it is hard not to see his move towards more collaborative, less conspicuous endeavours as a reaction to it. All of which makes his new film, Ex Machina, especially intriguing. It is the most fully immersive project he’s completed since he stopped writing novels and in many ways it seems like a culmination of his life’s work to date. His novels always felt cinematic and his screenplays — which have included 28 Days Later and Sunshine, both directed by Danny Boyle, and an adaptation of Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go — felt novelistic, characterised by smart, thoughtful dialogue of a kind that is almost extinct in films these days.

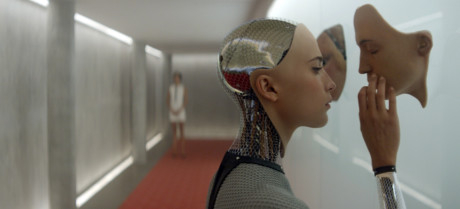

Now, as a director, he has brought together all these artistic and literary skills in Ex Machina to tell the story of an internet genius and hermit named Nathan (played by Inside Llewyn Davis’s Oscar Isaac) who has created the world’s first artificially intelligent robot, Ava (Alicia Vikander).

Not his film

Garland is immediately suspicious of such a smooth narrative of his career: it has certainly felt much more unplanned, haphazard for him. But mostly he takes issue with the notion that Ex Machina is his film, even though he conceived it, wrote the screenplay, designed the robot, drew the storyboards and was involved in every stage of its creation.

“I understand the premise, which is that directors own films,” he says, “but I don’t see it that way, I never have and I still don’t now.”

28 Days Later, his 2002 post-apocalyptic horror screenplay, was a huge critical and commercial smash: made for £5 million (Dh27.3 million), it returned more than 10 times that at the box office. It also began a relationship with DNA Films, Andrew Macdonald’s production company, which has since become a monogamous one for Garland. Mostly, however, it proved he could have a fulfilling creative experience without many of the downsides that come with writing novels.

“It was a terrific relief on 28 Days Later to watch from the sidelines,” says Garland.

Not all of Garland’s film work has enjoyed the same success as 28 Days Later — Sunshine, Never Let Me Go and Dredd (which he adapted for screen from the comic strip) were well-received but all lost money — and each production has provided valuable lessons for Ex Machina.

Oscar Isaac and Alicia Vikander, two of the most sought-after young actors in film, are joined in the cast by the brilliant Domhnall Gleeson, who plays Caleb, an employee of Nathan’s who is brought in to work out whether the robot passes the Turing test: that is, deceiving a human into believing that the robot, too, is human.

“There was a fight for them. The success is managing to persuade them to do it, that’s the success.”

Nevertheless, Ex Machina is accomplished, cerebral film-making: a love triangle of sorts that taps into a number of modern anxieties about technology and our potential obsolescence. These were evoked explicitly in December by Professor Stephen Hawking, who spoke of his fear that “the development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race”. Last June, Eugene Goostman, a computer programme pretending to be a 13-year-old Ukrainian boy for whom English was a second language, “passed” the Turing test — though with many qualifications — by convincing 10 of 30 judges from the Royal Society that it was human.

Again, Garland seems to have tapped into a cultural moment; a prescient knack he has shown from The Beach to 28 Days Later, which inspired a rebirth of the long-dormant zombie genre. He is, however, unconvinced by the current pessimism on artificial intelligence. “My position is really simple: I don’t see anything problematic in creating a machine with a consciousness,” he says, “and I don’t know why you would want to stop it existing. I think the right thing to do would be to assist it existing. So whereas most AI movies come from a position of fear, this one comes from a position of hope and admiration.”

Garland hopes Ex Machina will be the first of many that he writes and directs, but he’s taking nothing for granted. “What happens next is that this film comes out and it either will or won’t work, and my ability to make another film is hugely dependent on that,” he says.