The news my doctor gave me at my recent annual physical was surprising — and a little alarming: my blood tests showed that my thyroid was sputtering out. If I were a car, as my doc explained it, I’d be operating on two to four cylinders instead of the eight needed to motor through life. He told me that I had a condition called hypothyroidism and that I needed medication.

Like most people, I’m loath to acquire a new medical label, so I didn’t want to believe it. I had had some random complaints, but surely they were not enough for such a diagnosis.

I headed home and searched the Mayo Clinic’s website. I discovered that my patchwork of complaints — weird aches that sometimes made it painful to stand or move, and persistent dry skin that felt, well, vaguely reptilian — were more than random. I felt an intense fatigue that oddly made it difficult to rest and left me lying bolt awake at night, as if I’d been plugged into an electrical socket. Another symptom, a puffy face, helped me understand where my cheekbones had gone. Tack on weight gain, hoarseness and depression, and it all added up to hypothyroidism.

The condition affects about 1 in 20 Americans 12 and older. The majority are women and those older than 40. As a woman of a certain age, I had joined a club with millions of members. Ask around, and everybody and her sister seem to have it. Dealing with this condition requires good teamwork between doctor and patient, but it is very treatable.

There’s a long list of symptoms related to hypothyroidism, according to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and they vary. You could feel some, all or none of the symptoms and still have the condition.

“The number-one thing is that people feel sluggish,” said Peter Arvan, chief of the division of metabolism, endocrinology and diabetes at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. “They don’t move as fast. They don’t think as fast. They don’t react as fast. They are tired more. They sleep more.”

Weight gain is also a common complaint. But, as endocrinologist Robert Smallridge, immediate past president of the American Thyroid Association, points out, “for every one person we diagnose with hypothyroidism because they were gaining weight, there are many, many more who are gaining weight for reasons unrelated to their thyroid.” What’s helpful, he said, is to focus on how symptoms such as weight gain have changed over time.

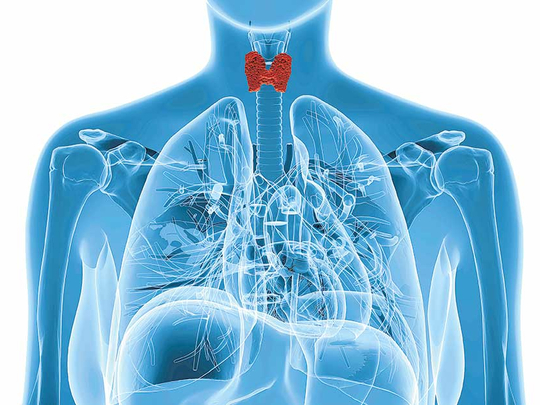

For a little gland, the thyroid has big a job. At just two inches long, this butterfly-shaped structure at the base of the front of the neck controls the metabolism and energy for virtually every organ system, Smallridge said. People tend to think of the thyroid in terms of weight and metabolism, but it also controls the heart, brain, muscles, digestion, breathing and fertility. “It has some say in everything.”

The thyroid gets its orders from its master gland at the base of the brain, the pituitary. Arvan described the thyroid as a furnace, supplying hormones (called T4 and T3) that help control metabolism, including calorie burning. T4, known as thyroxine, circulates in the bloodstream, and a tiny fraction of that T4 is continuously converted to T3, the active form of thyroid hormone.

The pituitary acts as the thermostat, regulating T4 and T3 levels. A thermostat sends a signal to a furnace when more heat is needed. Likewise, if more thyroid hormone is needed, the pituitary sends a signal called thyroid stimulating hormone, or TSH, to the thyroid to activate it.

If the thyroid doesn’t supply enough hormone, the pituitary keeps sending the TSH signal. Doctors measure the blood level of TSH in diagnosing thyroid problems. Hypothyroidism indicates too little thyroid hormone in the blood, as opposed to hyperthyroidism, which indicates too much hormone. Additional testing may be needed.

If you’re not getting enough thyroid hormone, medication usually helps. The synthetic thyroid hormone levothyroxine was the most prescribed drug, branded and generic, in the United States in 2014 and 2015, according to IMS Health.

Once you start on the medication, you will probably be taking it for the rest of your life, working with your doctor to stay on top of your condition. Finding the proper dose is an art as well as a science.

Before blood testing can determine if a levothyroxine dose is correct, the body needs at least five to six weeks to build up new hormone levels. Dosage is adjusted gradually, especially for older patients, Smallridge said. Most patients start feeling much better within a few weeks.

For my elevated TSH, I was prescribed an initial low dose of 25 micrograms of levothyroxine and instructed to double the dose after two weeks.

At first, I felt nothing — joints still ached and dry skin leathered on. On Day 2 of a double dose, I understood how the Tin Man must have felt after Dorothy squeezed the oil can. When I walked down stairs, the weird joint pains were gone. I felt peppier. Several weeks later, my skin started improving.

A couple of months passed, and I was swept up again by symptoms: what felt like a locking of joints in my back when I walked, accompanied by heavy, sad emotions. I went back for blood tests and got a bumped-up dose, and I am beating the symptoms. So far, so good.

Studies have shown that roughly 40 per cent of hypothyroid patients are on the wrong dose of medication. “It’s not just a matter of seeing somebody, giving them a prescription and never seeing them again,” said Smallridge, a specialist in thyroid cancer and the deputy director of the cancer centre at the Mayo Clinic’s campus in Jacksonville, Florida.

Certain drugs that treat seizures or depression can interfere with thyroid hormones. Changes in a woman’s oestrogen levels, due to being pregnant or starting or stopping birth control pills or hormone replacement therapy, can also have an impact on how well thyroid drugs work.

There are circumstances, Arvan noted, where the patient gets treatment and still does not feel better. In some of these cases, adding T3 in combination with levothyroxine can be effective. Such combined therapy is a subject of ongoing research, and if you’re considering this kind of treatment, it may be time to see a specialist.

In the United States, the leading cause of hypothyroidism is Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, in which immune cells attack the thyroid. For reasons that are not clear, this condition is seven to nine times more common in women than men, Arvan said.

Other causes of inadequate thyroid in the body could be the surgical removal of the thyroid (for cancer or other reasons); radiation treatment for Graves’ disease and other conditions; some medications, and problems with the pituitary.

The thyroid needs iodine to fuel itself and create hormones. Worldwide, the leading cause of hypothyroidism is inadequate iodine. This is not the case in countries such as the United States that supplement the food supply with iodine and where iodised salt has been used for almost a century. Iodine is also found in dairy, fish, some baked goods and eggs.

Iodine deficiency can cause mental and physical retardation, so pregnant women should take prenatal vitamins containing potassium iodide, Smallridge said.

For those whose hypothyroidism is well treated, no special nutrition or exercise is needed other than to follow the government’s dietary and fitness guidelines for all, Arvan said.

Now that I’m feeling better, the next part of my health journey is fighting the battle of the bulge — trying to drop those extra pounds I acquired in the past few years.

I take heart in Arvan’s words. After diagnosis, he said, it may be a bit easier to shed that extra weight. Dieting might be less of a struggle than it once was, he said, as my body is now burning calories more efficiently than when my thyroid was not functioning well.

Here’s hoping he’s right.

–Washington Post