The power of personal meetings in decision-making is well known. If you meet the prime minister over tea and dhokla (a snack from Gujarat) and mention in passing how you need to run around to get 100 licences before setting up a hotel, he is likely to remember the conversation when bureaucrats discuss single-window clearances to save precious man-hours and money.

So much happens at social gatherings — from impromptu meetings resulting in million-dollar deals to old boy networks working towards overlapping goals, such as the state providing tax holidays and land at less-than-market value to attract investors. Recently, US Secretary of State John Kerry travelled to India for a similar networking meeting, essentially because “America’s economy and security will increasingly be influenced by events in Asia”. The freest of markets is not really free — we call it investor-friendly.

Making new friends

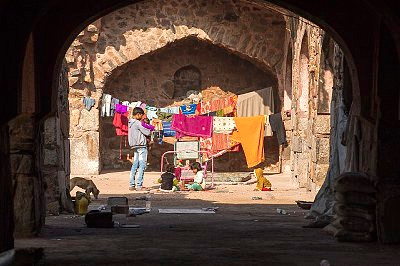

So, have you ever met a hungry person socially? The UN defines chronic hunger as a state, lasting for at least one year, of inability to acquire enough food to meet dietary energy requirements. Have you, perhaps, spent a day with a family living in a hamlet, that maintains human niceties with great dignity, sharing the only meal of the day with you — slivers of sukat or dry fish, some lentils and chapattis made of ragi?

If we dropped by uninvited to this hamlet, which has no water, electricity or McDonald’s, we would end up sharing the only meal the inhabitants are likely to have that day — and every day, except when the subsistence crops have just been harvested. It may be interesting to discuss the economics of getting food on the table with them. If we stretch our social and professional network to include those whose lifestyle includes only one meal a day, would the policy matrix then include their interests?

It is difficult to find a pro-welfare person these days in conversations about India — far away in Dubai, an economist at one of the world’s most reputable private banks, on whose advice millions can flow into India, is happy that subsidy is perhaps off the table with the new government, except that it isn’t. The World Bank, Time magazine, the World Trade Organisation (WTO), all have an opinion on it. The previous government’s National Food Subsidy Bill saw widespread international criticism. India has said that it will not ratify a trade facilitation pact until a permanent solution is found on food security.

In Bengaluru, the independent think tank Takshashila tells us subsidies are bad, bad, bad. Narayan Ramachandran, Fellow, Takshashila Institution and former Head of Global Emerging Markets, Morgan Stanley, tells GN Focus, “Removal of subsidies (petroleum products, fertiliser, food, etc.) is a good idea for any economy. Subsidies distort market behaviour and in doing so, create many problems including deficits and inflation. So it is in India’s long-term interest to reduce the impact of subsidies on its economy. Inflation is the worst form of tax on the poor. In summary, reduction in subsidies, market management of the economy and free trade in the long-term do benefit citizens by creating a low inflation growth economy...”

A recent report estimates about one-third of India’s population, or 363 million (2011-12), lives below the poverty line, spending between Rs32 (less than Dh2) and Rs47 a day. To put this in context, the number of votes that got this government into power with a landslide majority is 171.6 million, less than half this number. Going by sheer numbers it may be a good idea to meet a hungry person socially, keeping pity out of it.

Inclusive policies

Slightly above the poverty line, the economy includes a young man from a slum in Mumbai. On his way to college he passes by billboards selling cars, a house or moisturiser, looking for an income to bring home trickled-down versions of these. However, his college degree is not any guarantee to a job, unless it is supplemented by functional, legal and financial literacy — a task that Tata Institute of Social Sciences (Tiss) has undertaken by introducing the National University Student Skill Development Programme (NUSSD), designed to produce employable graduates in India’s rural universities. The programme relies on government funding and has been implemented as a proof of concept by the Ministry of Youth Affairs by partnering with the office of Advisor to the Prime Minister on Skill Development and Tiss.

Dr S Parasuraman, Director, Tiss, tells GN Focus, “Today I saw a news item stating one-third of the world’s poor are in India. When you have such a large population that is poor you need to do something. That support can only come through welfare. Irrespective of the political party the government belongs to, it will have to provide support to the poor.”

Turning the economic logic on its head, he asks, “What if I say, suppose if I were to give you more salary, you will buy more food, and inflation will go up?”

Maybe it would help if we didn’t have ready access to bottled water — glass or plastic, depending on the stars at the round table — as we ponder over matters that affect livelihoods. Perhaps we could have meetings at the foot of the hill in Jambhulpada near Mumbai in the summer, just before the monsoon, when we have to wait for the mud at the bottom of the hole to settle before dipping a vessel in to drink its contents.

Perhaps this is the reason every social scientist, researcher and development worker whose day job involves working with a few of the 363 million thinks, of course, policies need to be for everyone.

Former National Advisory Council member and development economist Professor Jean Drèze calls India’s National Security Bill a form of investment in human capital. In an interview with Tehelka magazine last August, he distinguished between financial cost and economic costs, adding, “Corporate hostility does not tell us anything except that the Food Bill does not serve corporate interests. Nobody is claiming that it does, nor is that the purpose of the Bill.”

Is there a middle path? Bringing in more efficiency is an answer. Professor Vijay Paul Sharma of the Indian Institute of Management (IIM) Ahmedabad has written a paper titled Food Subsidy in India: Trends, Causes and Policy Reform Options. Among other things, he suggests that states should participate in procurement, storage and distribution to improve efficiency. This may also help reduce cost of transportation and administration. He tells GN Focus, “Agriculture and food subsidies are justified but need better targeting/rationing to ensure that it reaches the targeted sections of the society. Stepping up investment (both public and private) in the sector is the need of the hour to have sustainable growth, which is more inclusive.”

Economists base their recommendations on various theories — listed at 50 in the last century alone. Perhaps a combination of cutting-edge education and friends with empty stomachs may lead to policies that ensure that no one goes to sleep hungry, in the short- and long-term. Shall we call it being subsistence-friendly?