Indian cinema has evolved rapidly over the past 70 years, though its birth goes back more than a century. While new technology has made for more sophisticated films, the basic script has also evolved to keep up with the life and times of people in contemporary India. Across the nation, from Bollywood to Kolkata and Kerala, cinema has evolved considerably, revealing the technicolour preoccupations of the nation’s citizens.

We take a look below:

FULL COLOUR

The first all-colour Indian film was released in 1953. “Aan, which starred Dilip Kumar and Nimmi, was shot in Technicolor, the most expensive colour format in that era,” says Director-Cinematographer Santosh Sivan.

“It was shot on 16mm KodaChrome Reversal negative and then blown up and printed by Technicolor Labs in London on 35mm release print. Faredoon A. Irani, the cinematographer, spent a few months in Hollywood training in the finer points on colour photography. It brought in a revolution in Indian cinema, showing us the world as we know it in real life.”

ANGRY YOUTH

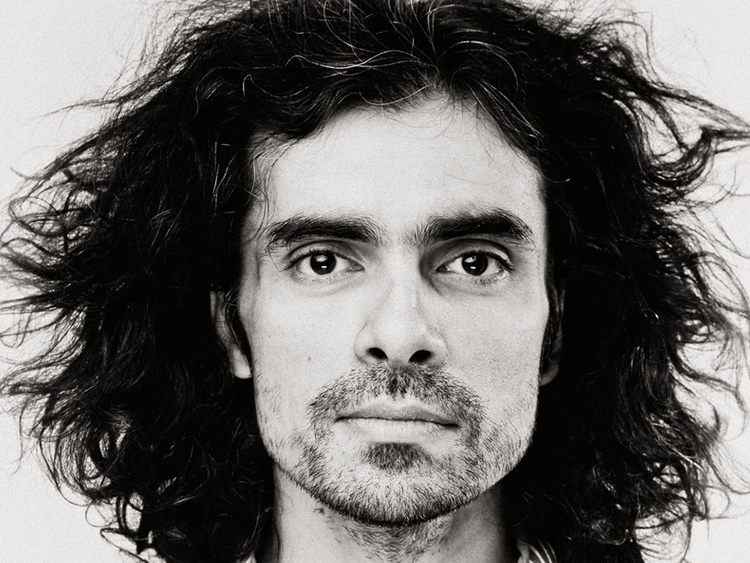

Around the time Indira Gandhi was prime minister, the emergence of the angry young man redefined the way Indian cinema approached justice and truth, says actor Shah Rukh Khan.

“We sympathised with him, even if he took the law into his own hands. We suddenly stopped being apologetic about the way we approached evils such as corruption,” he says.

CINEMATIC LANGUAGE

“In the initial phase of Indian cinema, the vocabulary, both literally and figuratively, was restricted to a few subjects: love, justice, good, bad, murder, poor and rich,” explains Director Kiran Rao.

“Movies with patriotic flavour found several takers in a post-independence era, which is what gave rise to the entire genre of Manoj Kumar films. They also had a clear moral discourse. From a highly political form of entertainment, Indian cinema has moved to stories of individual struggles of both moral and physical kind. It addresses issues of gender (Pink), personal quibbles and idiosyncrasies (Piku), issues of morality and immorality (Ugly or Raman Raghav 2.0), and the media drama that surrounds most events today (Peepli Live), or the cinema of Adoor Gopalakrishnan and Dasari Narayan Rao down south,” she adds.

SOCIAL REFLECTIONS

“Certain movies offered an insight into the preoccupations of the Indian society at different times in the life of the nation,” says Director Imtiaz Ali. “Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro (1983), a black comedy, revealed the dark underbelly of Indian society, a movie that dealt with corruption and politician-builder-media nexus in the most unrelenting way. Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge (1995) marked a shift in the way Indians thought.

“If the earlier movies were about rebelling against society norms, especially when you were in love, with DDLJ the tide changed. You now sought approval from your parents for your decisions. DDLJ marked a time when we spoke more to Indians outside India than within India. Farhan Akhtar’s Dil Chahata Hai (2001) was the story of the post-90s generation, which had never experienced the frugality of the first decades of the socialist era,” he adds.

BENGALI RENAISSANCE

It was Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali, awarded Best Human Document at the Cannes Film Festival 1956, that helped create an entire new language of cinema in India, says Sharmila Tagore, Actor and former Censor Board member.

“It helped Bengali cinema reach international audiences. The entire coming-of-age genre has been inspired by Ray’s cinema. Mrinal Sen introduced Marxist thought and ideology, the very foundation of politics in Bengal, to celluloid through movies such as Bhuvan Shome and Ek Din Achanak. Ritwik Ghatak’s movies like Meghe Dhaka Tara and Ajantrik depicted social reality in the 1960s and 70s Bengal. Kolkata for him was nothing more than a hellhole with extreme pockets of poverty and his cinema reflected that,” she adds.

ART CINEMA

While Satyajit Ray’s movies laid the foundation of art cinema in India, the credit of fostering it goes to directors such as Shyam Benegal and Mani Kaul, and to the Film Finance Corporation, which set out to finance and encourage a different type of film, points out Actor Shabana Azmi. “Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome was the finest in a genre of cinema that was unusual in treatment like Basu Chatterjee’s Sara Akash, Rajinder Singh Bedi’s Dastak, Mani Kaul’s Ashadh Ka Ek Din, M.S. Sathyu’s Garam Hawa, or Shyam Benegal’s Ankur. The obvious commonality between these works is an elimination of irrelevant songs and dances and a defiance of the star system.”

SOUTHERN POLITICS

The reorganisation of Madras into separate states along linguistic lines gave rise to a new era in cinema, with three more film industries emerging in the south, says Director Mani Ratnam.

“Mythological and religious cinema gave way to more contemporary movies such as Jeevitha Nouka (1951), a musical drama spoke about the problems in a joint family. Telegu cinema found their stories in social reality of that time, in movies like Prema Vijayam. Cinema down south also nurtured several future politicians and chief ministers,” he says.

In the 70s and 80s, actors and writers of the so-called guerrilla theatre brought their ideologies to cinema, which led to the rise of political leaders with a mass following, such as M.G. Ramachandran. Others remain aloof. “The cult of Rajnikanth is still going strong, four decades later,” explains Ratnam. “He is Garboesque in his determination to stay out of the public eye, and does not endorse politicians or social causes. Sum up his exaggerated mannerisms, defying the laws of physics and biology, and you still can’t put a finger on why people love Rajinikanth.”