“If you’ve ’eard the east a callin’, you won’t ever ’eed naught else,” Rudyard Kipling wrote in his poem Mandalay. For 300 years British men heeded the call of the east, flocking to India for colonial adventure. Many took Indian wives and the mixed race Anglo-Indian community became a distinct culture, dominating the public service as the arms and legs of empire. They were the “people of the railways” and diplomacy and civility were core skills as they navigated the linguistically and culturally diverse subcontinent.

The Anglo-Indian community’s chosen sport was field hockey and their excellence helped the Indian men’s team win six Olympic gold medals, producing greats like three time gold medalist Leslie Claudius. In 1979, Roger Binny became the first Anglo-Indian to play Test cricket for India but internationally he was preceded by an Australian of Anglo-Indian heritage — Rex Sellers — a humble leg spinner originally from Gujarat.

“There are two players that nobody ever said a bad word about — Brian Taber and ‘Sahib’ Rex Sellers,” said Ian Chappell, former Australian captain and Sellers’ South Australian team-mate. “Rex had his career cut short by injury but we got to see him at his best and he was a match-winner.”

Reginald Hugh Durning Sellers was born in 1940 in Bombay, now Mumbai, to Irene and Alf Sellers, the latter an officer engineer on the Indian Railways. “Rex” and his older brother Basil were raised in the idyllic surrounds of Bulsar, Gujarat, a small Anglo-Indian railway colony 200 kilometres north of Mumbai.

Now 75 years old, Rex Sellers is still in great form as he leafs through scrapbooks in the study of his Adelaide home. “My father would teach us cricket and sportsmanship on a half pitch in our backyard,” he says with a smile. “Bradman was our hero. We would take what we learnt down to the ‘maidan’ and play with the other boys.”

The Anglo-Indian world came crashing down on August 15, 1947, when India declared independence and Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister said, “We step out from the old to the new, when an age ends.”

A new anthem was sung, flags were changed and the Anglo-Indians faced a new social reality. “It was a memorable moment for every Anglo-Indian — we knew the power had shifted,” says Dr Gloria Jean Moore, author of five books on Anglo Indians including From India with Love, a history of the Sellers family. “We didn’t want to leave India but we were the human face of the British Raj and feared being murdered by mobs.”

Rapid social change brings tensions and without British Army protection, the Anglo-Indian community’s rawest fears were inspired when the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi in early 1948 threw India into chaos, curfews and riots. Targeted and indiscriminate violence killed hundreds of thousands of Indians from different communities and Sellers remembers feeling unsafe watching a riot outside the gates of the railway colony. Many Anglo-Indian families packed up and left, spreading like pollen around the Commonwealth to start new lives on their British passports.

Sellers’ mother Irene decided to take the two boys to the warmest city in Australia and if “favourable”, the plan was for Alf to join them a year later. This was a major decision for Alf, who was a man of high status in the Indian Railways, repairing bridges from his personal saloon car and managing over 1,000 men. He and his wife had heard throughout the community that Australian officials had used the ‘White Australia’ policy to reject the applications of some Anglo-Indians with darker skin. Irene suffered from vitiligo, a medical condition that causes loss of pigmentation and skin whitening and she was able to pass what some regarded as the unofficial colour test at the Australian High Commission.

Sellers remembers his mother breaking down whilst waving goodbye to his father as the ship Strathaird left the Gateway of India. Three weeks later they arrived in Adelaide in South Australia, the fabled “City of Bradman”.

“The Anglo Indians were the first Asians into Australia after the White Australia policy and nobody knew anything about us,” says Dr Moore. “The average Australian’s view of India were beggars, snake charmers and maharajahs. But we became neighbours and friends and are an Australian migration success story.”

The Sellers family first lived in an attic under a corrugated iron roof and Rex remembers “boiling and freezing”. Rex and Basil went to Kings College boarding school and Irene landed her first job in a dry cleaner ironing eight hours a day. It was a humbling realignment of status for a former “memsahib” with servants.

For the first year young Rex lost his bearings and struggled to fit in, suffering from similar racist taunts as those directed at his Aboriginal classmates. “I was linked with them due to my colour and was always introduced as being Indian,” Sellers explains. Sport opened doors and was his pathway to assimilation. “I went from introverted to outgoing and the racial taunts stopped once I was in a team.”

Sellers found refuge in cricket and his technique and temperament stood out. At the age of eight Sellers played in his Under-13s school team and he went on to captain the senior school XI. Like a lot of Australian kids he dreamed of wearing the baggy green. “It was all I could think about,” Sellers says.

Sellers chose to bowl leg spin, the high art of cricket, and what was impossible for most came naturally for him. Bowling leg spin requires bravery, resilience and toughness — Richie Benaud wrote about his “bleeding ring finger” at the end of each practice. Ian Chappell says “you have to be a bit kooky to bowl the stuff”. Leg spinners need to be thick-skinned, something Sellers knows well. “You can’t lose your temper or you’re gone. Keep calm and logically work through it,” he says.

In 1949 Alf Sellers resigned from his job, ending four generations of Sellers service to the Indian Railways. In his own biography he’d recall a friend farewelling him in Bombay and asking when he’d return. “I don’t know but first you will see my two sons playing cricket for Australia in India,” was his reply.

With his father settled in Australia, Rex continued to impress for his school and at local club Kensington came under the mentorship of former Test player Geff Noblet. South Australia Colts selection came in December 1959 and then at the age of 19 he made his first-class debut against reigning Sheffield Shield winners New South Wales. Alf sat proudly in the Adelaide Oval grandstand to witness his first wicket, Australian Test batsman Ian Craig.

Soon he was facing off against the 1960-61 West Indies touring team, dismissing Collie Smith, Seymour Nurse and Conrad Hunte, and showing he could compete at the highest level. All of a sudden he’d joined the ranks of cricket’s high priests of deception and magic, luring batsmen out of their crease like mermaids singing sailors to their doom. Future team-mate Ian Redpath called Sellers “a true purveyor of spin bowling, subtle with variations”. Sellers’ own philosophy was evocative: “Getting players down the wicket. Coaxing them out and sucking them down. It’s beautiful.”

In his first three seasons for South Australia Sellers played 23 matches and took 39 wickets at an average of 47 runs per wicket, an unspectacular return. He felt his game had plateaued. “I wanted to play for Australia but I struggled to hold my spot for South Australia,” he explains. “I got a reality check when I was dropped and for the first time had to consider doing something else in life.”

So he took a break and bought a delicatessen in Adelaide. At 21 his cricket career seemed behind him, so he threw himself into running his new business, rising early to pick up the fruit and vegetables.

But one man could not accept Sellers’ retirement — an old journeyman team-mate named Howard Mutton. Mutton badgered Sellers into practicing twice a week at 6am sessions before work. Mutton said he wanted to “try a few new things” and Sellers benefited from the sessions. “Over time I slowed down, got more loop, and overspin for drop and bounce. I had all the variety to entice batsmen into a mistake,” he says.

There is magic in persistence and after 12 months of private tuition, Sellers’ leg spin had pupated from caterpillar to butterfly. He had missed a whole season but was so confident that he sold his fledgling business and made himself available for the 1963-64 summer, terrorising batsmen for Kensington early in the season in Adelaide club cricket.

A stroke of luck came too when David Sincock, South Australia’s first-choice spinner, was late returning from a Lancashire League stint. Sellers was selected in his place for the season-opener against reigning Shield winner Victoria at the MCG. The game featured 13 players who had already or would eventually reach Test ranks and Ian Chappell remembers it vividly. “Victoria were very strong and I don’t know what clicked but Rex ambushed and steamrolled them,” he says.

South Australia won and Sellers took 8-149 in the match, announcing his new bowling style to Australian cricket. “Sahib is Back,” read the headline in the Australian Sport and Surfing Journal.

Sellers duly went on a wicket-taking spree and was soon described as the heir apparent to Australian leg spin guru Richie Benaud. At the other end bowling for South Australia was their West Indian import, Garfield Sobers, cricket’s Swiss Army knife; able to bowl everything from wrist spin to pace.

The Garfield and Rex Show delivered South Australia its first Sheffield Shield title in 11 years with Sobers taking 51 and Sellers 48 first class wickets, both more than any other Australian bowler for the season and for Sellers, at an average of 28 runs per wicket. “On the field he would get me wickets and off field we were friends and would go to the horse trots together,” Sellers says of his partner in crime.

In an Adelaide Oval tour match against the visiting South Africans Sobers showed the opposition no mercy, scoring a big century. It was a rare opportunity for a West Indian to play against South Africa and Chappell recalls Sobers asking South Australian captain Les Favell if he could wear his maroon West Indies cap to bat. Favell approved and Sobers thrashed the South African bowling with fury. Chappell asked Sobers why he had worn his West Indian cap and he replied: “They had never seen one and I thought they should have a good long look.”

Sobers and Sellers were both racially vilified on the field but Sellers maintains that these were isolated incidents and they were both mostly accepted. “At that level its mostly just playing against the other guy,” he says.

The South Australian players used to joke about Sobers and Sellers’ ‘suntans’ and he remembers inclusive team-mates who would back them to the hilt.

A key mentor for Sellers was Don Bradman, then a South Australian selector. He’d offer Sellers advice; “tighten your peaks and troughs”; “never read the newspapers during a game”. A firm friendship was forged. But behind every successful leg spinner there’s a brave and supportive captain. For Sellers that was South Australian skipper Les Favell, who granted him long spells and backed him when a batsman attacked. Former Test batsman Favell conspired with his spinner on complex plans to dismiss batsmen. Legendary Australian leggie Bill O’Reilly once wrote that leg spinners should be “enforcers” and Favell used Sellers so, backing him against the best in Australia.

These ripples of success were felt elsewhere in the Sellers family. Father Alf was a reserved man who did not make many friends in Australia and took great and active delight in his son’s success, painstakingly charting where every ball was hit off his bowling and then presenting the findings to his son for post-game analysis. That attention to detail helped Sellers become Australia’s premier leg spinner and speculation mounted that he could be selected for the upcoming Ashes and India tours. Sellers was shocked he’d been picked ahead of Chappell and Peter Philpott but his childhood dream had come true.

But Sellers’ selection triggered an uproar among the British media, some of whom questioned his eligibility, having been born in India and playing on a British passport. Australian prime minister Robert Menzies, a confirmed cricket tragic, personally intervened and fast-tracked Sellers Australian citizenship.

That 1964 Ashes touring team set off on the vessel Orcades and would be the last Australian team to travel by ship. Denis Compton wrote in his Test Diary 1964, that Simpson’s team was: “the most underrated and frequently written off Australian team I had ever known. Even before they left for England they were dismissed as of no account and the return of the Ashes little more than a formality.”

Sellers had experienced niggling hand problems before the tour but passed the medical. Captain Bobby Simpson wrote in Captains Story: “I had great hopes for Sellers. He’s a very good, high flighted leg spinner who looked the type to give curry to those counties that don’t play this sort of bowling well.”

The Australian team had their first net practice at Lord’s and the English media converged to watch Sellers bowl. The next day the AAP headline read “Sellers startles in Lords practice” with England spin legend Jim Laker declaring, “Heavens, I thought this chap was slow through the air. If he bowls at this pace, and with this control, on our wickets, he will be a sensation.”

But on the morning of the Duke of Norfolk’s XI at Arundel, Sellers woke up with a numb and swollen bowling hand and was referred to a specialist, who discovered a major cyst under a tendon attached to his spinning finger. In the resultant operation doctors removed part of the tendon and the spinner missed 10 tour games and the entire first six weeks of the tour.

Unable to press his claims, Sellers watched on as the first two Tests were drawn and his countrymen won the third. Needing only a draw to retain the Ashes, captain Bobby Simpson took a hardnosed approach in the fourth Test, batting England out of the game by making a record 311 runs. Sellers was 12th man that day so remembers the English being demoralised at the end of play and debutant Fred Rumsey shouting: “If that’s fookin’ Test cricket, you can stick it up your fookin’ arse.”

Six weeks in, Sellers eventually played his first tour game and ended up with 30 wickets at a respectable average of 37 in his 13 games, including 5-36 against Yorkshire. Each time his hand and finger would end up sore and continue to throb through cold English nights. Although he couldn’t break into the test team, Sellers was happy with the tour. “Once they picked Tom Veivers as spinner he kept his spot. I was very happy to reach 30 wickets,” he says.

But it was onward to India and Sellers set off for Madras (now Chennai) with a group headed by Bill Lawry.

In the Sellers family history, From India with Love, Rex’s team-mate Ian Redpath recalls Sellers’ reception in India: “Hundreds of fans greeted him as a hero returning home and knew about his childhood in India,” said Redpath. “As the Australian team walked through the crowd they shouted ‘Which one is Sellers?’ and asked to see ‘his magic fingers’.” Sellers laughs now. “Even though I had forgotten the language I was appointed the mediator between the team, the bus drivers and our ‘chokras’ who carried our gear and would sleep on top of it to prevent it being stolen.”

But Sellers still stood at the periphery of selection when the series was locked at 1-1 and the teams flew together to Calcutta to play the decider at Eden Gardens. The night before that game the Australian team held its selection meeting and Simpson nodded to Sellers saying, “You’re in the side Sahib.”

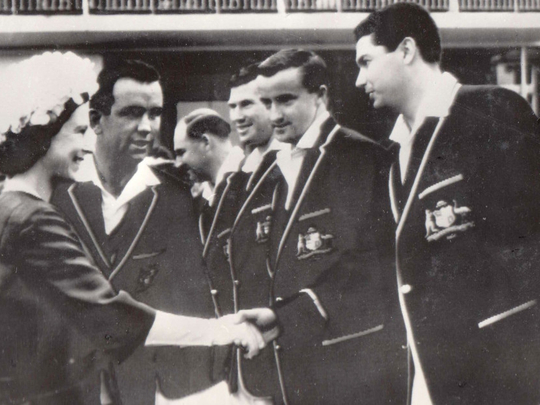

At Eden Gardens on the morning of October 17, 1964, R.H.D Sellers became Australia’s 230th Test cricketer and the first player of Indian descent to do so (Dhaka-born Branson Cooper was the first Australian cricketer born in what was then considered India but he was of English heritage).

When Sellers walked out to bat at 167-8 in the first innings there was applause from the Indian crowd but no fanfare. He bowled five overs in the first innings for figures of 0-18 and with that, a monsoon swept in and the Test was abandoned and the series stuck at stalemate.

Sellers had to be content with reconnecting with his Indian roots, leading his wary team-mates out every day to try different curries. In Bombay, Sellers reunited with Cyril Pearce, the old friend of his fathers who was delighted to see Alf’s prophecy come true. He was also visited by a group from the Western Railways.

The following summary of their exchange appeared in the October 1964 issue of Western Railway magazine: “Rex Sellers is the son of a former Railway man Mr W.A. Sellers and naturally with a celebrity with such an affinity to us, we could not miss the opportunity of meeting Rex and extending a welcome on behalf of the Railway. Rex greeted us with a full-fledged Australian accent and for a moment we were nonplussed as to whether we would understand him at all. But with the mention of the Railway, and Bulsar in particular, all barriers were down and with his smiles and gestures, we knew we were at home with Rex. Rex confessed that he had lost his Gujarati language but had fond memories of the neat cottages and gardens and cricket games on the Bulsar ‘Green’.”

After seven-and-half months away Sellers returned to Australia but developed another cyst — this time a larger lump and more difficult to operate on. Strongly advised not to have an operation that could shrink the tendon and limit flexibility, Sellers nevertheless played another six games for South Australia to finish out the season. But he could not grip the ball properly or bowl for long periods, the key role of a leg spinner. Only four wickets came at an average of 70 runs per wicket and he promptly informed captain Favell and the selectors that he could not continue. After a single Test appearance he was done.

Rather than risk permanent damage, Sellers retired from bowling and continued to play as a specialist batsman for Kensington, improving enough in this facet of his game to be selected in the top order for South Australia in 1967, but it was a brief return to first-class ranks. At 27 and with a second child due with his wife Ann, he retired for good with a record of 121 wickets at 38.45 in 53 games.

Sellers continued to involve himself in club cricket, coaching at Kensington and also leading Adelaide to a premiership in 1975. He was a South Australian selector from 1979 until 1983 and since his old captain’s death in 1987 he has chaired the Les Favell Foundation, which supports underprivileged youth in the Adelaide cricket community. In aid of his other great love, Australian football, he used his diplomatic skills to broker a hostile but successful merger between his beloved West Torrens and Woodville, becoming the inaugural President of the Woodville West Torrens Eagles.

Sellers was awarded a life membership of the South Australian Cricket Association, having served as vice president for 13 years and won the Order of Australia Medal in 2013 for his services to the game. Before retiring at 74, he oversaw the planning and strategy for the redevelopment of the Adelaide Oval in time to host the highly anticipated clash between India and Pakistan at last year’s ICC World Cup. For Sellers this was a proud moment and “a perfect time to retire”.

Sellers carries the regrets of any sportsman whose career is cut short by injury, particularly acute given that he had finally mastered the difficult craft of leg spin. “But I’ll never know if I was good enough to keep going at that level,” he laments. “It’s unresolved.”

Sellers says his success in cricket came down to his parents’ sacrifice, in particular that of his mother Irene. “She was the brave one, a real pioneer,” he says.

Rex Sellers played in a time when controlling one’s temper was seen as a strength, not a weakness. His captain Favell gave him the “Sahib” nickname — an Indian term that equates to “gentleman” — on account of the manners and affability he’d inherited from his parents. The unofficial motto of British Empire was “Keep Calm and Carry On” and according to Chappell, Sellers embodied this philosophy: “I don’t think I’ve ever seen him get angry. If something bad happens he shows no emotion.”

But Sellers’ legacy lies in not lingering on what could have been, rather shining a light on what was. He’s been a gentleman, a gifted administrator, the first Indian-Australian Test cricketer and an entertainer who during one carefree summer in the 1960s created some cricketing magic alongside the game’s superhero, Garfield Sobers. Rex Sellers has the final, humble word: “It was simply an honour to be part of.”

— Guardian News & Media Ltd, 2016