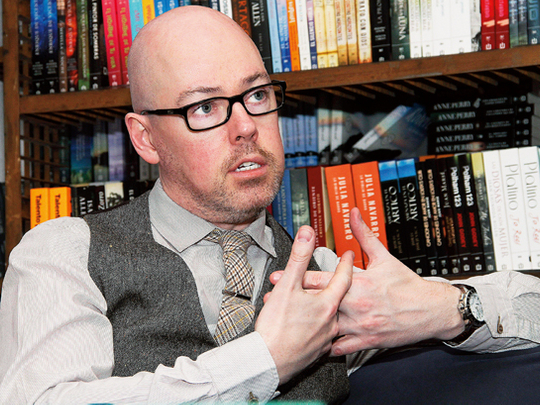

John Boyne laughs when he’s asked whether he really did take less than three days to write the first draft of his most famous work, the award-winning The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas. “Yes,” he says. “I wrote for 60 solid hours, only taking a break between chapters for a cup of tea or a sandwich. Usually I have an idea for a book and I think about it for a long time before starting to write, but when I had that idea I started writing it the next day... The story seemed to take me over and I couldn’t walk away from it.”

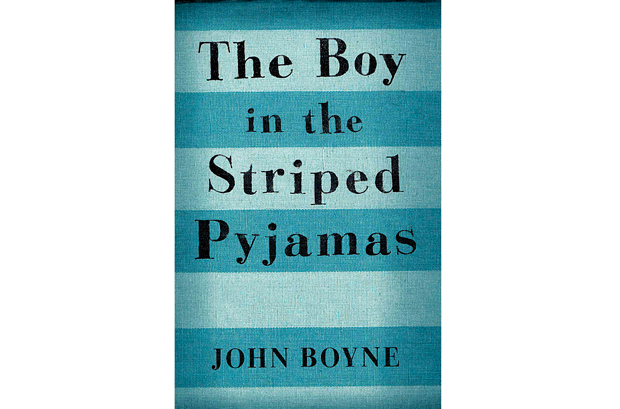

The book explores the relationship between two children who live in adjacent homes separated by a fence. It went on to become a New York Times best-seller and a critically acclaimed film directed by Mark Herman.

But Boyne, who’s single and lives in Dublin, is far from a desk-bound hermit. In fact, the award-winning writer – he bagged two Irish Book Awards and the Bisto Book of the Year (now known as CBI Book of the Year) a literary award presented in Ireland to writers and illustrators of books for children and youth – treats his work like any other day job.

“Always an early riser, I’m usually up by 6.30am at the latest,” he says in an exclusive interview with Friday. “Four mornings a week I go to the gym first thing. It’s important for a writer – who naturally leads a sedentary life – to get exercise as this fuels the creative process. I work on a new novel in the morning and early afternoon, finishing around 2.30pm. I never write at night.”

Boyne, 42, has the distinction of being one of the few authors to have been simultaneously successful as both an adult and children’s fiction writer, having sold more than 4 million copies of his 12 books, including the most recent Stay Where You Are Then Leave. His works have also been translated into 46 languages.

“I enjoy writing for the different audiences,” he says. “In my adult novels I tend to write from a first-person perspective and get deep inside the psychology of a character; in my books for younger readers, I write in the third person and have a more global view on the story. But the process of writing a novel is what interests me, it’s not as important who the audience is intended to be.”

Boyne started writing at the age of 11 “by taking characters from fairy tale books I loved and writing new stories for them.

“I love the process of building a story towards an honest resolution and knew from a very young age that this is what I wanted to do with my life,” he says.

Sensitivity is integral to everything Boyne does, writes, says and approaches… Everything except mediocre young adult fiction.

“I think there are two types of children’s fiction being published today – challenging, uncompromising novels that respect the intelligence of their readers from writers such as Malorie Blackman, [Noughts and Crosses], Philip Pullman [His Dark Materials trilogy] and Michael Morpurgo [War Horse].

“And then there are the trilogies, the quadrologies and the longer series that all have their eyes on the film adaptations, the theme park rides and the Happy Meals.”

Mass-selling serial novels like The Hunger Games and The Twilight Saga, Boyne feels, lack in intelligent content unlike CS Lewis’ Narnia series, of which he is a great fan.

According to the Irish author, a book should not be written with the idea that it would be made into a movie. “I’m always more interested in the former and have no patience for the latter,” he says.

How to survive a zombie apocalypse

‘I’m £25,000 more beautiful than I was before’

'I have no memory of my wedding day'

Changing lives is child’s play

Royals raise awareness for the care of terminally ill children

His interest in writing has paid off, but success didn’t come easy and involved six years of writing while working at Waterstone’s bookshop to pay the bills after gaining two degrees in English Literature and Creative Writing from the renowned Trinity College, Dublin and University of East Anglia, where he won the prestigious Curtis Brown award for the best writer of prose fiction.

But Boyne puts paid to the misconception that creative writing courses teach people how to write. “They provide a forum where people can be inspired by each other and have readers for their work,” he says.

“I was very young, only 23, when I undertook that course. I went in thinking I knew everything about writing and it broke me down almost immediately so that I had to start from scratch. I had no plan B; it was writing or nothing.”

He persevered in writing and the rest is history. Which is just as well, because Boyne has a habit of creating narratives around characters and stories that already exist – one that draws him in part to historical settings time after time in his novels.

Boyne says it was never his intention to set the majority of his book against major historical events – right from his first novel The Thief of Time covering over 250 years of world history from Paris in 1758 to Hollywood of the 1920s.

History, Boyne feels, serves as the perfect narrative vehicle for getting across universal and significant themes.

“Looking back, I’m a little surprised. I didn’t set out with that [setting most of his stories with a historical backdrop] in mind. I only wanted to write.”

However, some critics have claimed his historical fiction has elements of the escapism of fantasy fiction. To this, Boyne dryly suggests I Claudius by Robert Graves, William Golding’s Rites of Passage trilogy or David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas.

“A good novel is a good novel; the time period it is set in is irrelevant,” he insists.

And he doesn’t accept being squared away as a historical writer. “I simply call myself a writer. How other people categorise what I do is a matter for them.”

His latest book for adults, The Haunted House, is a spook fest set in 19th Century London.

And his next A History of Loneliness – “A fully contemporary novel that runs from the 1960s to the present day” – is due out this September.

While the extravagance of 20th Century Russia was the setting for The House of Special Purpose and the exoticism of Sydney of The Terrible Thing That Happened to Barnaby Brocket, A History... is set in his native Ireland.

He says there are many stories that can be told using historical settings but with contemporary themes. “Especially in the case of children. They are a resilient lot and can handle more serious topics than we give them credit for.”

It’s a belief he bolsters in Stay... a novel about a young boy dealing with the repercussions the First World War has on his family. “I think if a story is written in a careful and sensitive way, not to traumatise young readers but to move them, then children are capable of coming to terms with any reality from the past,” he says. “We shouldn’t write down, but create interesting, unexpected stories for young people with endings that will leave them asking questions.”

Does it take years of research to get the historical facts right? “Not really,” he says, adding that he always chooses a subject, time or place that interests him.

“I start with novels that were written at the time my book is set because one falls much easier into the language of the time and the idiom by doing that.

“If possible I spend some time in the place where the book is set. For example with The House of Special Purpose, I wrote most of the Russian sections in the Winter Palace.

“When I start writing, however, I put the research away and just start to create. The ability to maintain a balance between truth and imagination comes with the experience of having written so many novels and having devoted my adult life to writing fiction.

“I feel that I understand the novel structure and am able to instinctively make decisions about the proper line between facts and imagination.”