It was during the pink month of October seven years ago that I was diagnosed with breast cancer, had surgery and started on the long journey towards putting myself back together again. “Treat cancer with the disdain it deserves,” one friend told me, and that’s what I did. There are several things about being ill. One is how busy it makes you; appointments, people coming to see you, support staff, more appointments (one involving long needles), check-ups, it’s a whirlwind that keeps your mind off what is really happening.

Cancer is a complicated illness. The process went like this: I had a routine 50th birthday mammogram courtesy of the National Health Service in Britain and thought nothing of it. The sheer horror of getting a recall letter ten days later is still with me, one of those moments when I was reading the words but my brain didn’t want to register what it said. Unless it has happened to you, you can’t guess what it’s like.

We were due to go on holiday, so I rang the hospital and said I would make an appointment when I returned. “We’ll open a little bit early and see you on Monday morning,” they said. I think that was the moment when, in my heart, I knew it was going to be bad news. It was the first of many times I went into my shell, and kept the news to myself. After the biopsy, the doctor said, “We are almost certain it is cancer,” but there was a ten-day wait for the results to be confirmed. After that, everything sped up and I had surgery after another phone call.

“The surgeon says if you can come in on Thursday she will postpone a cosmetic surgery procedure she has booked and see you instead.” I heard myself saying, “Please don’t inconvenience anyone, I can wait.” My head still hadn’t caught up with the news that was making my heart beat so loud it was drowning out everything else. My surgery was carried out to the sound of Motown – my surgeon’s choice after I’d jokingly suggested Handel’s Messiah. “You need me awake, Sue,” she joked as her team did a little dance while I went under the anaesthetic.

I was in hospital for four nights. The morning after I went home a friend dropped in. “Why are you in bed?” she asked. “I’m catching up on four nights of lost sleep,” I told her. We both laughed, but I noticed that neither of us used the word ‘cancer’. Just as I was feeling better, and four weeks after I’d gone back to work, 21 days of radiotherapy began. By then, I’d received all the flowers, visits, presents and good wishes I could want. I’d had an early diagnosis, I was feeling great, and I wasn’t in need of chemotherapy. I was lucky.

A battered soul

I had a 120km round-trip journey to the radiotherapy unit every day. My husband took me on day one, and then I took over – until I realised that I’d come up against something that didn’t agree with me. I turned to my friends, and learned a valuable lesson. Within hours I had a rota of drivers for the next three weeks. “At last, something practical we can do for you,” they told me. By the end of the treatment, my skin was burnt to a crisp inside and out, and I was ill.

The next few months are a blur. My soul felt battered and I was tired to the bones. Some days I couldn’t concentrate. It was as if my body needed every scrap of energy to recover and had nothing left for things like thinking. I’d pick up a book and end up staring at the wall. Little by little, I preferred being alone. I went back to work, but making the journey into London from our home in the countryside, sitting at my desk and making my way back home again were all mountains to climb.

My eyes had a pinched, weary look and had lost their sparkle. I heard myself telling everyone I was fine. I wanted the minimum fuss while my mind and body got their puff back. I wore a padded jacket in fear of someone accidentally knocking into me, and I realised I was trying to keep a distance for another reason – I really didn’t feel like describing how I felt. Soon it was the pink month of October again, and the terror of my first annual check-up. When my surgeon told me, “All’s well,” a layer of gloom lifted and I could breathe again.

A few weeks later, sitting in a traffic jam, I got irritated by a driver and laughed out

loud and I realised I was getting back to normal. Around this time an opportunity for my husband and I to take jobs in Dubai came up. We needed a change and we wanted an adventure, so a few months later we were both sitting behind new desks in a newspaper office in Al Quoz wondering for the second time in 18 months what had hit us. This time, it was voluntary and not life-threatening! I decided not to tell people I’d had cancer.

I didn’t want my identity to be summed up by an illness and we were among strangers. I sort of felt it was no one’s business, and I’d had enough of my battered left breast being such public property. That October, after a second year all clear, my husband and I did the BurJuman Pink Walkathon and I was surprised to feel tears in my eyes as hundreds of pink balloons were released. They represented so many women with a story to tell. I prayed in my head, “Please let them get the treatment they need and let it be a success.”

I’ve just had my seven-year all clear and, because my surgeon is retiring, she has signed me off. Officially, I’m no longer a cancer patient. My last appointment with her was a moving experience. She had never said a wrong word and I valued the first piece of advice she gave me, “If you’ve got questions, ask me and not the internet. You only need answers about your cancer, not everyone else’s.” To this day, I’ve never even Googled “breast cancer”.

My brush with radiotherapy has left me with lymphedaema in my left arm, which I will have for ever. It’s a tiresome condition that means my lymphatic system is sluggish. I exercise every day, wear a compression sleeve for a few hours every day, and have regular drainage massages. It’s a pain, but it won’t kill me and it is the perfect example of the unexpected ways cancer can affect you. There isn’t much treatment for it, but I’m told there might be a pill one day that will keep it under control.

An ‘uncomplaining patient’

On the one hand, I’m fine. On the other hand, I’m not quite as untouched by the whole experience as I might have been. As I say, I’m one of the lucky ones, an “uncomplaining patient” as my surgeon called me. That doesn’t mean I can’t complain on behalf of lots of other women, though, and before I start I apologise to anyone who thinks I’m being churlish. The pink breast cancer awareness month began in 1985. Millions of people have raised millions around the world since then, and they have my admiration.

One friend even ran the Race for Life with my name pinned on her back. So where is all the money being spent? I was treated with a drug that was created in the 1950s, and a treatment that was pioneered in the early 1900s by, among others, Marie Curie. Healthcare is scary; it all depends who you are, where you live, what your government thinks is important, even what’s fashionable.

There’s no point being angry about this, but there is good reason to keep asking the awkward questions. Things have moved forward and I am alive thanks to this, but we must not let the pink haze wrapped around breast cancer make us think “they” are doing “their” best. I never use the word “cured” and I never allow myself to get too cocky about my all clears.

The ‘you never know what’s around the corner’ syndrome is deep in my personality and is constantly battling it out with my inner optimist who sees life as a daily miracle. Cancer is horrible, but it’s also a bit like travellers’ yarns. People don’t want too much detail, just a snapshot rather than the whole photo album. Without realising it, you edit your own experience, sum it up in one sentence, and keep the rest deep inside you somewhere. That is the loneliness of cancer.

My job has been to get all of this into perspective and carry on. In fact, my ambition is to become the longest-living woman in my family tree. My grandmother made it to 91.

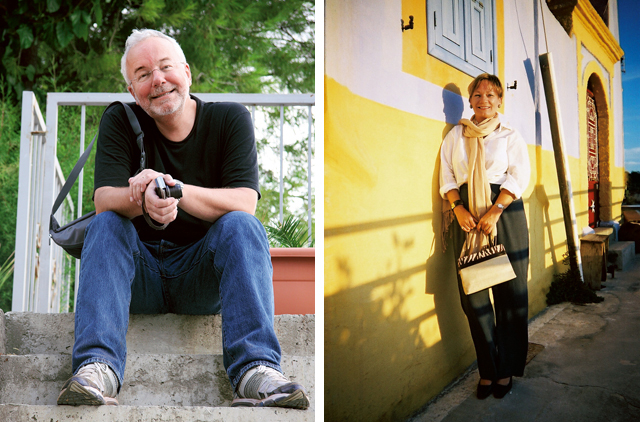

I didn’t go through breast cancer alone. Here’s what my husband, Colin Simpson, says are a few of his memories:

“The idea of sitting in a hospital room listening to a doctor confirm in a soft, sympathetic voice that my wife had cancer was way beyond my imagining. And then it happened. Plenty of other bad moments followed – taking Sue to hospital for a dreadful procedure involving a long piece of wire on the morning of surgery, her terrible paleness when she was brought back from the operating theatre, seeing the pain and distress caused by the radiotherapy... You do your best to help, but of course events have moved out of your control. I am so grateful to Britain’s National Health Service, which detected the cancer in time for it to be treated successfully, and the team that cared for her. The experience changed me; I lost my peace of mind. But I love and admire Sue more than ever for the way she took it all in her stride and got on with her life.”