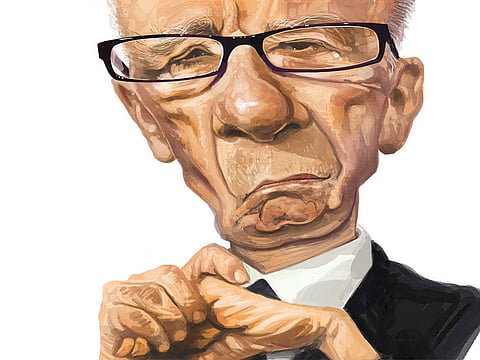

Rupert Murdoch: The world’s first truly global media mogul

Rupert Murdoch has taken huge gambles and created whole new industries

When media mogul Rupert Murdoch closed Britain’s biggest newspaper, the News of the World, in July 2011 — after it became mired in allegations of phone hacking — he had hoped the move would draw a line under the scandal. The chairman and CEO of News Corporation feared the scandal was threatening to taint other titles published under his UK operation, News International.

However, the company was later beset by further allegations of hacking and corruption, and has led to — among other things — the withdrawal of a bid to take full control of satellite broadcaster BSkyB, the arrest of numerous Sun journalists, and the resignation of Murdoch’s son James from several positions in the family business.

Yet despite his company’s involvement in several inquiries and police operations, Murdoch — now 84 years old — has taken an increasingly hands-on approach to its problems.

His profile as a key player in News International’s fate became particularly prominent after he was questioned by British MPs in July 2011 — a meeting which was disrupted when an onlooker attacked the media mogul with a foam pie, leaving Murdoch’s young wife leaping to his rescue.

He later went on to launch the Sun on Sunday, which sold 3.26 million copies in its first week — a figure not bettered by any UK newspaper for years.

The octogenarian even took to Twitter — reaching out to supporters and attacking further allegations against the company.

He also agreed to give evidence to the Leveson Inquiry into press standards.

In July 2012, Murdoch announced that he had resigned from a string of directorships controlling News Corp’s UK newspapers — at NI Group Ltd, NewsCorp Investments and Times Newspaper Holdings.

News Corp plans to split into two companies, separating its publishing interests from the more lucrative TV and film side.

Murdoch is expected to chair both businesses but to be chief executive only of the TV and film enterprise.

Political manipulation

Murdoch, who inherited a taste for the press from his father, is no stranger to controversy. He began his career aged 22 when his father Sir Keith, one of Australia’s most distinguished newspapermen, died and left his son a half share in two Adelaide papers.

Born in Australia in 1931, Oxford-educated Murdoch had a natural flair for popular journalism and a tendency to fall out with his editors. Although he spent much of his career denying he interfered too much.

“I think that I give my editors tremendous freedom and the only people who claim that I don’t give them enough freedom now are the people who wouldn’t know how to use it,” he once said.

There was steel beneath the boyish exterior, as the British discovered when he arrived in 1968 to buy the News of the World.

Within a year he had added the ailing Sun newspaper, relaunching it as an irreverent tabloid.

Circulation soared thanks to its sex-and-sensation formula and it went on to became Britain’s biggest-selling daily paper.

But his papers were frequently accused of political manipulation, distorting the news to ensure his political allies won elections.

His critics, of which there are many, have called him a vulgarian and a cynic who had degraded standards of journalism by pandering to a sensation-seeking public. His loyal admirers have always heaped praise on to him, applauding the businessman for his ruthlessness, energy, and astonishing willingness to take risks. In 1986, by now owner of the Times and Sunday Times as well, Murdoch moved all four newspaper titles into a heavily fortified printing plant, and sacked 5,000 workers.

The ensuing battles with pickets outside Fortress Wapping heralded a revolution in Fleet Street, and an end to over-manning and restrictive practices. A television revolution followed. Already the owner of the Sun, he went on to introduce Sky, the satellite TV service to Britain.

Setbacks

Despite critics calling it downmarket rubbish, satellite dishes soon became commonplace and Sky gobbled up its rival, BSB, to become hugely profitable.

Before long, Sky could afford to bid more than hundreds of millions of pounds for the television rights to Premier League football.

In June 2010, News Corp had been bidding to take over the 61 per cent of BSkyB it did not already own. But the company abandoned the bid in July 2011 after the phone-hacking scandal emerged.

In the US, where Murdoch had bought 20th Century Fox, he won a bigger prize, establishing America’s fourth television network.

Along the way, he became a US citizen to circumvent rules banning foreigners from owning television stations.

Fox shows such as the “Simpsons” cartoon series sold around the world, but Murdoch continued to suffer setbacks.

In the 1980s his empire nearly crashed when its debts mounted to a staggering $8 billion.

He survived to buy Star TV in Hong Kong, broadcasting by satellite to the whole of Asia.

When the digital revolution swept television, promising many more channels, pay-per-view programmes, home shopping and home banking, Murdoch’s TV stations were at the forefront.

But in Britain his monopoly of digital broadcasting technology led to fruitless calls for new rules to limit power. He dismissed any suggestion that he was too powerful.

Global media mogul

“People say we’re anti-competitive, when we do something which is open for anybody in the world to do,” he once said.

He closed down one newspaper, the loss-making Today, in 1995, partly out of pique when the British government passed laws limiting how much of the media one company can control.

During the Conservative’s reign in the 1980s and early 1990s, Murdoch’s publications were generally supportive of the government, but that all changed when John Major eventually left Number 10.

Prior to his election, Murdoch invited Tony Blair to Australia. He also told his papers to tone down their attacks on Labour.

The Sun went further, to the surprise of many, endorsing Blair at the 1997 election.

But Murdoch backed winners and made it clear that once the Labour Party’s fortunes declined, it would switch allegiance.

Murdoch’s involvement with politicians does not stop at the British government.

He has had dealings with Canadian Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper, US President Barack Obama and the former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd over the years.

Married three times, he divorced his second wife, Anna, after 32 years together and tied the knot with TV executive Wendi Deng in June 1999.

Murdoch has always put his business interests first.

He has taken huge gambles and created whole new industries.

In the process, his opponents claimed, he manipulated governments, lowered standards and sidestepped regulations, to become the world’s first truly global media mogul.

He was stridently anti-monarchist in his views, rejecting the hereditary principle.

Yet his sons Lachlan and James are primed to take up the reins of power in the Murdoch dynasty.

Source: BBC.com

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox