Disappointment is a uniquely human condition, the flip side of our capacity for creativity and invention. Only humans “dream things that never were” and “say ‘Why not?’” as George Bernard Shaw famously put it. This capacity gives us flying machines and pocket computers. It also gives us rising suicide rates in countries around the globe, from the United States to India to New Zealand.

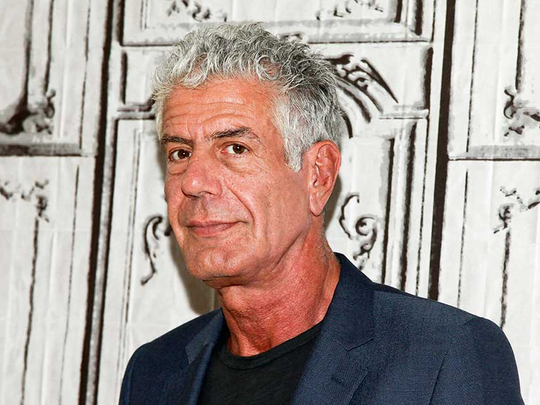

To be unhappy enough to end it all, a person must first imagine a condition of greater happiness, then lose hope that the greater happiness can be achieved. Anyone this side of Dr Pangloss in his best of all possible worlds can start down this dismal path. Because there is no limit to human imagination, there is never a shortage of greener pastures. Though we’re shocked when the rich and famous kill themselves, the Kate Spades and the Anthony Bourdains, we shouldn’t be. Neither wealth nor celebrity nor any other endowment quiets the human impulse to wish some things were different than they are.

John Keats, for instance, was a handsome and massively talented young man of 23 when he pronounced himself “half in love with easeful death.” Ruminating on the sweetness of an unthinking nightingale’s song, he catalogued just few of the disappointments of human consciousness:

“The weariness, the fever, and the fret

Here, where men sit and hear each other groan;

Where palsy shakes a few, sad, last gray hairs,

Where youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies;

Where but to think is to be full of sorrow

And leaden-eyed despairs . . .”

A strong case can be made that modern society does a poor job of preparing 21st-century humans for the inevitable ebb and flow of discontent. Indeed, British therapist and philosopher James Davies has buttressed that case formidably in a scholarly tome titled The Importance of Suffering, and follow-up bestseller, Cracked: Why Psychiatry is Doing More Harm Than Good.

Davies argues that we have created a culture that assumes happiness to be the normal, healthy human condition. Deviations from the blissful path - sadness, anxiety, disappointment — are thus treated as illnesses in search of a cure. This “harmful cultural belief that much of our everyday suffering is a damaging encumbrance best swiftly removed” gets in the way of a more robust response, he writes: namely, approaching unpleasant emotions as “potentially productive experiences to be engaged with and learnt from.”

I would not go quite as far as Davies does in his scepticism of psychiatric medicines; clinical depression and anxiety are serious illnesses that have become more manageable with the help of prescription drugs. But he is unquestionably right that these chemical compounds alone will not make the world appreciably happier. Despite widespread use of the prescription pad, we’re seeing an epidemic of opioid abuse and rising suicide rates.

Historically, cultures have celebrated the value of endurance in the face of suffering and the understanding that comes from adversity. This was the bedrock on which Robert F. Kennedy stood during his finest hour, when he broke the awful news of the Rev Martin Luther King Jr’s murder to a predominately black audience in Indianapolis 50 years ago: “My favourite poet was Aeschylus,” Kennedy said. “He wrote: ‘In our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God’.”

Few leaders speak now of pain as a positive good. There’s scant room in today’s Prosperity Gospel for Paul’s notion of the kind of “comfort, which you experience when you patiently endure the same sufferings that we suffer.” It’s hard to imagine a president writing, as Abraham Lincoln did to a despondent young West Point cadet: “Your good mother tells me you are feeling very badly in your new situation. Allow me to assure you it is a perfect certainty that you will, very soon, feel better — quite happy — if you only stick to the resolution you have taken.. . .”

Lincoln could write that with conviction because he knew the depths firsthand. His friend Joshua Fry Speed grew so alarmed at young Lincoln’s despondency that he removed every sharp implement from the future president’s room. Biographer Joshua Wolf Shenk writes persuasively that living with deep sadness was a key to Lincoln’s success: “With Lincoln we have a man whose depression spurred him, painfully, to examine the core of his soul; whose hard work to stay alive helped him develop crucial skills and capacities ... and whose inimitable character took great strength from the piercing insights of depression ... forged over decades of deep suffering and earnest longing.”

–Washington Post