Of the myriad times since adolescence that I have returned to the story of Don Quixote de la Mancha, there is one I choose to remember — that I cannot help but remember — as we commemorate the 400th anniversary of the death of Miguel de Cervantes. That reading, in October 1973, took place among a distraught group of captive men and women who, like me, had sought asylum in the Argentine Embassy in Santiago, Chile, after the coup that overthrew the democratic government of Salvador Allende.

In an atmosphere in which a thousand future exiles were suffocating in rooms designed to host cocktail parties, I joined a group of some 30 refugees who were reading it aloud together. Conceived as a sort of literary therapy to fight depression among us, I soon discovered that these readers had much to teach me. Many of them had come to our country from the failed revolutions of other Latin American lands, had been locked away for prolonged periods of time, and suffered torture and banishment. They instinctively understood Cervantes, who like them had been the victim of astonishing adversity and had become immensely resourceful in a cruel and disenchanted world.

Indeed, the defining experience of Cervantes’s life was the harrowing five years starting in 1575 that he spent in the dungeons of Algiers as a prisoner of the Barbary pirates. It was there, on the border of Islam and the West, that Cervantes came to appreciate the value of tolerance towards those who are radically different, and it was there he discovered that of all the goods men can aspire to, freedom is by far the greatest. While awaiting a ransom that his family could not pay, confronted with execution each time he attempted to escape, watching his fellow slaves tormented and impaled, he longed for a life without manacles. But once he returned to Spain, a crippled war veteran neglected by those who had sent him into conflict, he came to the conclusion that if we cannot heal the misfortunes that assail our bodies, we can, however, hold sway over how our soul responds to those sorrows.

“Don Quixote” was born of that revelation. In the prologue to Part 1 of his novel he tells the “idle reader” that it was “begotten in a prison, where every discomfort has its place and every sad sound makes its home”. Whether that jail was in Seville or in Castro del Rio, this recurring experience of incarceration forced him to revisit the Algerian ordeal and put him face to face with a dilemma that he resolved to our joy: either succumb to the bitterness of despair or let loose the wings of the imagination. The result was a book that pushed the limits of creativity, subverting every tradition and convention. Instead of a rancorous indictment of a decaying Spain that had rejected and censored him, Cervantes invented a tour de force as playful and ironic as it was multifaceted, laying the ground for all the wild experiments the novelistic genre was to undergo.

Cervantes realised that we are all madmen constantly outpaced by history, fragile humans shackled to bodies that are doomed to eat and sleep, make love and die, made ridiculous and also glorious by the ideals we harbour. To put it bluntly, he discovered the vast psychological and social territory of the ambiguous modern condition. Captives of a harsh and unyielding reality, we are also simultaneously graced by the constant ability to surpass its battering blows.

Those of us reading “Don Quixote” in 1973, in an embassy we could not leave, surrounded by soldiers ready to transport us to stadiums and cellars and, ultimately, cemeteries, responded viscerally to the novel. That continuous exaltation and practice of liberty, both personal and aesthetic, was inspiring. This faith was epitomised by a passage from Part 2 of “Don Quixote” that moved us to tears.

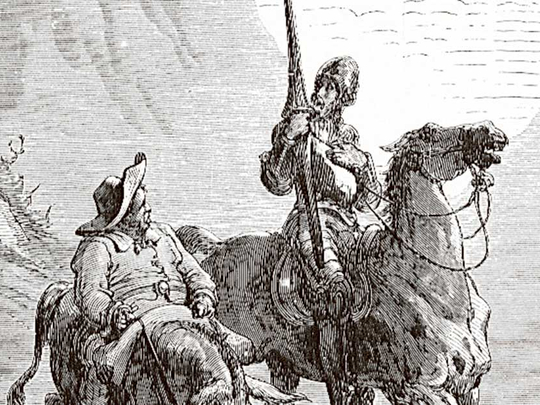

Sancho Panza has been made governor of a fictitious island by a frivolous duke. The lowly squire proves to be a far wiser and more compassionate ruler than the noblemen who mock him and his master. One night, doing the rounds, he comes upon a young lad who is running away from a constable. The boy gets cheeky, and the ersatz governor sentences him to sleep in prison. Infuriatingly, the prisoner insists that he can be put in chains but that no one has the power to make him sleep: staying awake or not depends on his own volition and not on anyone else’s commands. Chastened by the lad’s independence, Sancho lets him go.

It is an episode that has stayed with me. If I recall it now, it is because I feel it contains the essential message Cervantes still has for today’s desperate humanity.

True, most of the planet’s inhabitants are not in prison, as Cervantes so often was, nor do they find themselves confined within walls, like the revolutionaries in the Argentine Embassy. And yet we live, as if captured, in a time of violence and inequality, greed and stupidity, intolerance and xenophobia, marooned on a planet spinning out of control — like lunatics sleepwalking towards the abyss.

Cervantes died 400 years ago, and yet he continues to send us words — like the wisdom of that boy threatened by Sancho Panza — that we need to meditate upon before it is too late. Nobody has the power to make us sleep if we don’t wish it ourselves. Cervantes is telling us that our besieged, besotted, captive humanity should not lose hope that we can awaken in time.

–New York Times News Service

Ariel Dorfman is the author, most recently, of “Feeding on Dreams”.