NEW YORK: Like other little boys, Baraka Cosmas Lusambo loves to play soccer. When he hears music, his feet tap and his face breaks out into a wide smile. During summer pool time recently, he used his left hand to toss a ball through a basketball hoop while red arm floaties keep him above water.

The joy vanished, though, when he was reminded of the night men armed with torches and knives burst into his family’s home in western Tanzania, knocked his mother unconscious and sliced off his other hand.

“We were simply sleeping when someone just arrived,” Baraka said. “They came to me with machetes.”

Baraka has albinism, a condition that leaves its afflicted with little or no pigment in their skin or eyes. In some traditional communities of Tanzania and other countries in Africa, albinos, as they’re often called, are thought to have magical properties, and their body parts can fetch thousands of dollars on the black market as ingredients in witch doctors’ potions said to give the user wealth and good luck.

Baraka and four other children with his condition have escaped the threat, at least temporarily, brought to the United States by the Global Medical Relief Fund, a charity started by Elissa Montanti in 1997 that helps children from crisis zones get custom prostheses.

Montanti, moved by an article she read about Baraka, reached out to Under the Same Sun, a Canada-based group that advocates for and protects people with albinism in Tanzania and had been sheltering Baraka since his attack in March.

When Montanti asked if she could help him, the group asked whether she would also help four other victims get prosthetics, as well. She agreed and brought all five to live for the summer at her charity’s home in New York’s Staten Island while they underwent the process of getting fitted for and learning to use prostheses about two hours away at Philadelphia Shriners Hospital for Children.

“They’re not getting their arm back,” Montanti said. “But they are getting something that is going help them lead a productive life and be part of society and not be looked upon as a freak or that they are less than whole.”

Albinism affects about one out of every 15,000 people in Tanzania, according to the U.N. Anyone with the condition is at risk, and people attacked once can be attacked again

The government there outlawed witch doctors last year in hopes of curtailing the attacks, but the new law hasn’t stopped the butchering. There has been a sharp increase in attacks in Tanzania and neighboring Malawi, according to the UN Tanzania recorded at least eight attacks in the past year.

The children have been in the U.S. since June. Once they receive their new limbs after a few months, they will return home to safe houses in Tanzania run by Under the Same Sun. Montanti’s fund will bring them back to the U.S. to get new prostheses as they grow.

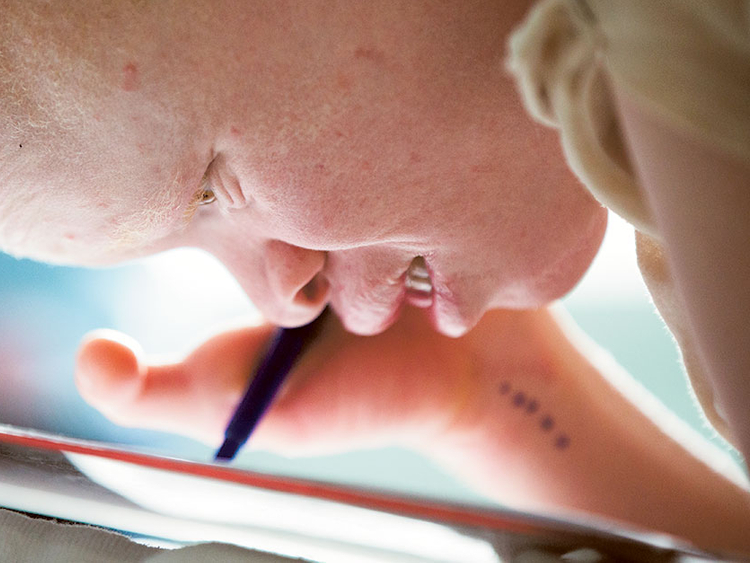

On a recent visit to the hospital, Baraka was fitted for a prosthetic right hand. He poked at the flesh-colored plastic hand as it lay beside him on the examination table. His atrophied right arm was barely able to lift the prototype prosthesis, but that was to be expected” it would grow stronger once the prosthetic hand was in place.

One of the other victims, 17-year-old Kabula Nkarango Masanja, said that her attackers asked her family for money, and that her mother offered the family’s bicycle because they had none. The attackers refused, held the girl down and in three hacks cut off her right arm to the armpit. Before leaving with her arm in a plastic bag, her attackers told her mother other men would be back to take her daughter’s organs - but they didn’t return.

The girl thinks constantly about her missing limb.

“I feel bad because I still don’t know what they did with my arm, where it is, what benefits they derived from it - or if they simply dumped it,” said Kabula, a tall girl with a sweet voice who once sang “In the Sweet By and By” for the nonprofit group.

Between trips to the hospital, Montanti has filled the children’s summer with typical American activities. In late July, the children went to a swimming pool for the first time ever. Volunteer lifeguards helped them navigate the water.

Montanti said that they’ve become like her adopted kids, and that she has grown especially close to Baraka.

As the group gathered recently for a barbecue dinner near the pool, Montanti interlocked one of her hands with Baraka’s remaining one and whispered, “I love you.”