Throwing my car keys in my bag, I checked I had everything. I was about to drive 250 kilometres and was ready except for one thing – my daughter Meagan, 20. She was running late and I was about to call her when there was a knock on my front door. I glanced at my watch – it was 8.45am on a Saturday and I didn’t want to hit traffic. We’d arranged to drive from my place in Pensacola, Florida, to Tallahassee to see my eldest daughter Michelle and her husband Scott. The next day was Mother’s Day and Meagan’s twin Carmen was at a college graduation out of town and my son Alan was in Arkansas county almost 1,300 kilometres away.

“It would be nice to see at least two of my children on Mother’s Day,” I’d said to Meagan the night before. She’d smiled. “Sure, Mum,” she’d said. Now, hurrying to open the front door, I wondered if she’d forgotten her keys, but my sister-in-law Barbara was standing there. Fear pulsed through me when I saw her – she was pale, and looked scared and in shock.

At first I thought something was wrong with my brother. “Renee, there’s been an accident,” she said. “It’s Meagan. She didn’t make it.” That’s how she told me my daughter had died. It was very matter-of-fact, not sugar-coated. I have no idea how she found the strength to do it. I began to scream, hollowed out by those awful words. It was as if someone had ripped out all my insides and there was nothing left except for this terrible wailing, this awful sound coming from me.

Then I collapsed. I didn’t faint – it just felt like everything had been sucked out of me and I couldn’t stay standing. I pulled myself up before I started screaming again.

A blur of grief

The rest of that day was a blur, but I know Barbara told me there had been a car accident. Someone – they believed a drink-driver – had ploughed into her best friend Lisa Dickson’s car at a traffic light, killing them both instantly. The police had tried to contact me, but one of the officers on the scene knew that Meagan was my brother’s niece. It’s a really small town. Everybody knows everybody. So he contacted my brother and Barbara to see if they could help get the message to me.

It seemed so unreal – just the day before I’d had lunch with Meagan. She’d asked me to pick her up at Carmen’s new apartment, where she was staying for the summer break from college. The twins couldn’t have been more different. Carmen had just moved in, dumping her stuff before going out. The flat was a mess; stuff hanging out of unpacked boxes everywhere.

“Come in,” Meagan had said when I arrived. “I want to show you something.” She had that sparkle she’s had since she was a little girl, and that mischievous look in her eyes. She was excited to show me what she’d done. I gasped when I saw – the flat was spotless. She had unpacked all the boxes to surprise her sister when she got home.

That afternoon I’d sat across the table over lunch looking at how beautiful Meagan was, soaking up our time together. Afterwards she’d gone to meet friends, but I’d called her at 11.30pm to check our travel plans for the morning. “What are you doing now?” I’d asked. “I’m with Lisa sitting on the beach, looking up at the sky,” she’d said. “It’s really beautiful.” The pair were best friends and had been hanging out with their friends at the beach.

Lisa would drive them back later. “I love you,” we both said, before hanging up.

Less than 12 hours later, I was making the rounds, telling my ex-husband Philip

and the rest of our devastated children Alan, Michelle and Carmen, that Meagan was dead.

We were all in shock, especially as no one knew exactly what had happened, just that the other car had hit Lisa’s and her car had hit a tree. “I want to see the scene of the accident,” I said. It was eerie seeing the four tyre marks pointing towards the tree, which had been stripped of its bark where Lisa’s car had hit it. I asked the police what had happened. “Have you arrested anyone? Was the driver drunk?” I asked.

They told me they’d drawn blood from the suspect, Eric Smallridge, who looked like he was impaired, but hadn’t arrested him. They wanted to wait for the test results first. Meanwhile I had to organise Meagan’s funeral. The following month she was supposed to be a bridesmaid at her brother’s wedding. The dresses had been picked out already. Now, numb with grief, I was picking out her coffin.

More than 1,500 people came to the funeral to say goodbye. Philip and I were stunned at the number of people who came up to us at the service introducing themselves as ‘Meagan’s best friend’. That was just like her. She loved people and made them feel so special. Afterwards I slumped into grief. I tried to kid myself that Meagan was simply away at college, but I’d break down sobbing, knowing she was never coming back. And now one question nagged away at me: “why?”.

The trial

It wasn’t until months later at the July trial of Eric Smallridge that I found out the full details of what had happened that night. Eric was a student who had been drinking all day before the crash on May 11, 2002. While Meagan and I were having lunch he’d headed to the beach to hang out with friends. By the time he’d got in his car to drive home around 2am, blood-alcohol test results would later prove he had drank the equivalent of 14 beers.

An eyewitness would later say she was driving at the time when she noticed Eric’s vehicle, a Jeep Cherokee, driving fast and erratically. It pulled up alongside her Mazda as they stopped at a red light. Eric was in the middle lane. The eyewitness was in the left lane and in the right lane was a white car.

She told the court that she heard Eric rev his engine before he and the white car took off very quickly when the traffic lights changed. She thought they were racing. But Eric said his car had died shortly before he headed off and his friend helped him jump-start it. He says he was revving the engine to make sure it didn’t conk out. Either way, both cars took off across the lights, where the three-lane road merges into two. Lisa was sitting at the lights on a road that runs perpendicular to the direction Eric was going. She was sitting in the far left lane waiting to turn left when the lights changed.

Eric said he thought the white car was going to cut into him, so he turned his car to avoid that driver. In doing so he hit Lisa’s car, sending it into a tailspin and making it crash into the central reservation before it hit a nearby tree. The girls’ necks broke upon impact and by the time their car had stopped, their bodies had been thrown into the back seat.

Of course, I was angry that this man’s actions had caused the death of Lisa and Meagan. But what particularly hurt was that he pleaded ‘not guilty’ to the two charges of vehicular homicide. How could he deny that he was responsible when his blood-alcohol level proved he was inebriated?

Seeing Eric at the trial was hard, but I wanted to stay. I needed to know what had happened to my daughter and her best friend. At the end of the week-long trial, the jury found Eric guilty on two counts of DUI (driving under the influence) manslaughter. I knew the conviction wouldn’t bring Meagan back, but I felt a sense of satisfaction knowing he wasn’t going to get away with what he had done.

I went home expecting to feel better, as if the verdict would heal the pain. Of course, it didn’t. But over time I didn’t feel so raw, so angry and then one day I woke up and decided to forgive Eric. That might sound shocking, but I knew I would never completely heal if I didn’t.

I could have hated him forever and the world would have told me I had the right to do that, but it wouldn’t have me any good. Holding a grudge wouldn’t achieve anything – I would grow old, bitter and angry. Eric must have felt guilty and wanted to make amends, because he wrote me a letter apologising for his actions. It was like a burden had been lifted, and I no longer had to hide behind a facade.

'I forgive you'

A few weeks later I stood in the courtroom at Eric’s sentencing hearing, reading my victim impact statement, telling Eric how his actions had affected my life. At one point I looked him in the eyes and said, “I forgive you”.

He broke down, and through his tears said, “I know I’ve done wrong and I need to be punished.” As he said those words, I knew in his heart he was truly sorry.

The judge gave him 22 years imprisonment; 11 years for taking the life of each girl. Philip, my children and I – each of who have individually agreed to forgive Eric too – were relieved and pleased at his sentence. We felt that it was just.

I walked away expecting never to see or hear from him again, but my mother put herself on his call list, so he could try to mend bridges. One day – about a year after his sentence – I was at my mum’s house when he called her from prison. “Renee’s here,” she said. “Do you want to speak to her?”.

It felt weird listening to his voice, hearing him say sorry again and again. But I realised that had taken a lot of guts and it meant a lot to me. We kept in touch through letters and phone conversations, and on Mother’s Day and at Christmas he sent me cards. Some people couldn’t understand how I could be in touch with the man who killed my daughter, but others did – parents who’d gone through the same thing.

I met a man who lost his wife and daughter when they became the innocent victims of a drag race gone wrong. He too had forgiven the man who killed his family, and together they visited schools to teach teens about road safety. That’s when I decided to start The Meagan Napier Foundation, which I created in March 2004. I wanted something positive to come out of Meagan and Lisa’s deaths, so I started travelling around the state giving presentations to warn school children and adults about the dangers of driving under the influence.

About a year later, my family, Lisa’s relatives and I decided to ask the court to cut Eric’s sentence in half, so he would serve both 11-year terms concurrently rather than consecutively. We knew he had fully appreciated the extent of his actions. Eleven years is enough time for him to repay his debt to society and go on to make a positive impact upon his release.

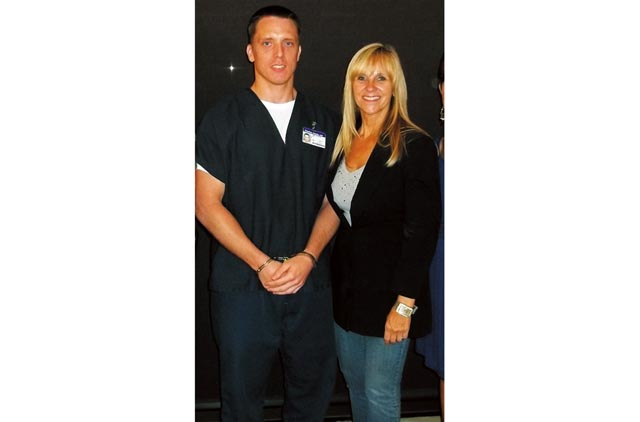

Eric asked if he could join me on the presentations and in 2010 he was given permission to travel with me to schools and military bases to tell his story. I spoke first, telling the audience about Meagan and Lisa, sharing pictures and telling them how their lives were taken by the actions of a drink-driver. Then I watched their reaction as Eric was led in, wearing his prison suit and in chains. They were confused. They had just heard a mother tell a heart-wrenching story of loss and then they saw the killer before them.

They heard his story; how he started drinking in high school when he’d hang out with his soccer teammates on the weekends. When he was old enough to drive – at the age of 16 – he was given a van and would drive his friends around. By the time Eric was at college he was so used to drinking and driving that he felt confident enough to do it without getting into an accident or killing anyone.

The people at the presentations saw that he is a good person who made a bad choice that changed his life and mine forever. I also took pictures of Lisa’s crumpled Mazda with me to illustrate the impact of the crash. We’ve done more than 100 presentations together.

Seeing Eric mature over the past ten years has affected me greatly. He has a college degree, which he finished in May 2003 before he went to prison, and he’s also worked for the Goodwill charity on a work-release programme. He was allowed out of prison last November.

Eric is the same age as my son Alan, and I have grown to love him as a son. He is 34 now, and it is going to be hard for him to reenter society, get a job and pay his bills. But I want the best for him. I want him to find a place to live and find someone to settle down with.

Some people on the internet have criticised me for forgiving my daughter’s killer, but I know in my heart that Meagan would be proud of the decision I made, because it’s what she would have done too.’’

Renee Napier, 53, lives in Florida, US