Zubair Hasan grins as he packs his bag and prepares for school. The seven-year-old has a new set of books, coloured pencils, a smart new pencil case, a clean pair of shorts and a shirt – he cannot believe his luck.

Until recently this boy – like many others in Lalmonirhat, a small town close to Bangladesh’s capital, Dhaka – did not even have a school to attend. The nearest was a few kilometres away and parents like his could not afford to pay for books or transport to send their children there.

That was before November 2012 when Mohammad Alaluddin – a former resident of the town who had moved to Dubai as a wheelchair attendant for Emirates Airline – decided to help his old community by setting up a small school to provide free education.

Mohammad wanted to do his bit so the next generation would have it a bit easier than he did when he was growing up. “I’ve experienced how even a little education can improve a person’s life, and I want the children in the slum where I lived to have a better life when they grow up,’’ says the 52-year-old.

Until a few years ago Mohammad used to set off from his tiny ramshackle hut in a slum in Dhaka at 5am and drag his cycle rickshaw through the heavily congested and highly polluted roads of the city all day. By late evening, he would barely make around 100 taka (Dh5). “Tears used to well up in my eyes because I knew that it would hardly be enough to purchase a kilogram of rice and some fish for my wife and four children, who would be waiting at home for me to return with my earnings so we could buy some food.’’

In a country where a kilogram of rice costs around 50 taka and a loaf of bread 40 taka, he was struggling to make ends meet. “We often had just two meals a day,’’ says Mohammad, who lived with his family in a corrugated tin-shed room with mud floors. There was just one makeshift bed in the house and it had no toilet or bathroom. The hut, which was covered with cloth and plastic sheeting, leaked whenever it rained and an open drain ran in front of the main door. He and around 300 other people in the slum were forced to cook, clean and wash in these conditions.

His meagre earnings left him with little savings and the family lived a hand-to-mouth existence. “I couldn’t even afford to put my children in school,’’ he says.

The turning point

Mohammad’s life was turned around in 2006 when he came into contact with the Dhaka Project, a charity devoted to improving the lives of Dhaka’s slum children through education and social transformation. “I immediately enrolled my three younger kids aged between five and 12,” he explains.

His elder son was 16 and already doing part-time jobs including helping out in a nearby garage to help the family. Along with free schooling for the children, the Dhaka Project, founded by Maria Conceicao and run by a small team of volunteers, also provided his family with essentials such as rice, lentils, clothes and a sum for house rent, among other things.

“For the first time in our lives, my family and I were able to enjoy four meals a day and could sleep on proper beds,” he says. “Maria Conceicao and later, the Maria Cristina Foundation also provided us with sheets and blankets, and gave us medical aid as well.’’

The Maria Cristina Foundation is an organisation based in Dubai that provides secondary education to children who live in the slums in Bangladesh. Maria believes in trying to break the cycle of poverty by giving their parents marketable skills for employment.

Mohammad hadn’t been able to complete his school education because his family was too poor. He was expected to work to contribute to the family, so he had no option but to become a rickshaw puller – a common job in Dhaka. “I always dreamt of providing the best for my children. I wanted them to be educated so they could get a decent job in the city. To do that I knew I would also have to improve myself – learn a new skill, a new language like English – so I could earn more.’’

When Maria introduced a new initiative called The Catalyst in 2009, which aimed to help adults in Dhaka learn new skills, Mohammad seized the opportunity and promptly enrolled to learn basic English and how to prepare for job interviews. He used to attend classes in the evenings after work. “It was tough because I was very tired, but I wanted to realise my dreams,’’ he says.

Within a year he was able to speak a little English and he found a job in a grocery shop set up with the help of the same charity in his village, Kurigram in the Lalmonirhat district. “For the first time I was able to dream to improve my life and my family’s,’’ he says.

In 2011 Mohammad was among a group of seven men that the Maria Christina Foundation brought to Dubai in the hope of finding employment. He landed a job at Emirates Airlines earning Dh2,300 per month; “the equivalent to what I would earn pulling my rickshaw for two years,” he says.

His family stayed in Dhaka as he couldn’t afford to bring them to Dubai on his salary. “I missed them a lot, but I was happy that I was earning well so could give them a better life,’’ he says. Mohammad spent very little on himself, preferring to save as much as he could.

A world of possibilities

On a vacation to his home country at the end of October 2012, Mohammad experienced an epiphany of sorts. Witnessing the stark reality of the lives of the people there – the poverty, destitution and daily struggle to quell the pangs of hunger – he was overwhelmed.

“It’s not that I was unaware of the conditions in Lalmonirhat,’’ he says. “But this time I felt as if I was viewing them with fresh eyes.’’ His life in Dubai had unveiled a whole new world of possibilities and opportunities and watching such hardships back home stirred deep emotions within. “I wanted to do something that could bring about a positive difference in the lives of my fellow countrymen,’’ he says. And he didn’t have to think about his next course of action for long.

His mentor Maria Conceicao – a former flight attendant who gave up her career to set up the Maria Cristina Foundation – gave him some priceless advice that he put into action: ‘Education is one of the most powerful tools in breaking the cycle of poverty’. His own life was a perfect example of that.

During his first week back in Bangladesh, Mohammad decided he would set up a school for poor children in the slum. He discussed it with some village elders who embraced the idea. The same week he was given a plot of land by the local government and he began constructing a one-room building.

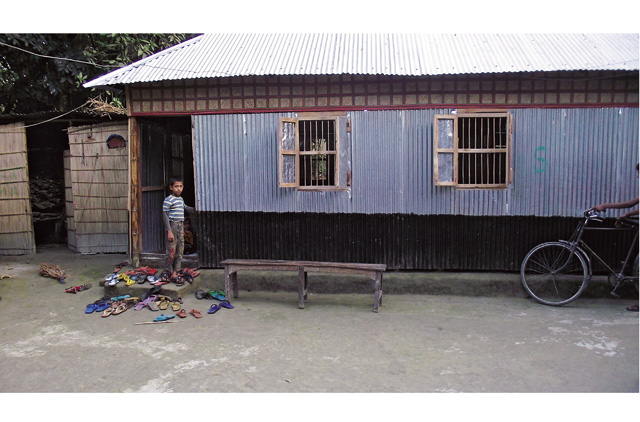

In less than a week the structure of corrugated metal sheets was ready. It cost him around Dh1,200 to build. Mohammad proudly named it Helping Hands School and announced that it would start functioning immediately. He also identified two graduates who volunteered to teach at the school for free.

'A huge incentive'

Mohammad went from house to house asking parents to send their children to the school, where not just education but also a meal and uniforms would be provided for free. Mohammad footed the bill for all of this. “I felt that would be a huge incentive for parents to send their children to school, because in a village every pair of hands is viewed as an extra source of income,’’ he says. “I managed to convince some of the parents and within a few days 25 children enrolled in my school.

My family was overjoyed with the initiative.’’ Mohammad also set up a committee to manage the day-to-day administration of the school in his absence. The idea is to begin with just one class of students in grade one and gradually extend the school to grade ten.

“The 25 students are doing well in grade one at the school,” says Mohammad, smiling. “As well as meals and uniforms, I’m also giving them all essential school supplies such as pencils, pens, books, papers and erasers.’’ Every few months Mohammad sends stationery including books and uniforms to his school in Lalmonirhat. “It is not easy because I must be careful about what I spend. But to see the happiness on children’s faces when they get the school stuff is worth it all,’’ he says.

The monthly expenses for running the school come to around Dh1,200, including school supplies, clothes and food for the children. Once the children complete grade one, the school will expand to teach them grade two and a new set of grade-one pupils will be taken on. “I have very few wants, so my salary is more than sufficient to meet the expenses of my family and these children,” says Mohammad.

Although the school is housed in a tin shed at the moment, Mohammad is enlisting the help of a few people to raise funds so a proper school building can be erected. “Dubai-based Up and Running, an integrated sports medical centre, has already committed to supporting us with funds to upgrade the school,” he says.

Mohammad Rafiq, the father of one of the children, Mohammad Rizwan, is all praise for Mohammad’s initiative. “He is doing a great service to our village. Unlike government schools that may offer free education, Mohammad is giving the children a proper meal, as well as clothes for really poor children and all school supplies. We are sure the students will do well in his school.’’

Parvez Hasan, father of Zubair, is happy his son is able to study in a school close to his home. “Mohammad is our friend who has made it big, but he has not forgotten his roots. He has come back to help the poor people in his community. We are willing to offer all help to him,’’ he says.

Sumon Azad, 20, another beneficiary of the Maria Cristina Foundation who is employed in Dubai, is sponsoring the expenses of one child at the school. Mohammad hopes that in time, more people will offer sponsorship and he will be able to fulfil his dream of running a fully functional primary school in Lalmonirhat.

“Maria is my hero,” he says. “She brought the first ray of hope into my life when there was none. I constantly look to her for inspiration and this school is just a small attempt to pay back the remarkable benefits I have gained thanks to her tireless efforts.”

Tell us the story…

Do you know of an individual, a group of people, a company or an organisation

that is striving to make this world a better place? Email us at friday@gulfnews.com or the features editor at araj@gulfnews.com