“Capitalism and other Americanisms may be taking over in other cities, but there are many in Kolkata (and India) still attracted to Soviet Russia ideologies,” says Gautam Ghosh, a former newsreader with All India Radio. Ghosh has been working as the programme officer of Gorky Sadan — otherwise known as the Russian Cultural Centre of Kolkata — for the last 40 years.

Gorky Sadan sits on the busy arterial AJC Bise Road. A statue of Maxim Gorky adorned with flowers greets you as you walk into the foyer area. Beside the statue is the exhibition hall where a photo exhibition by Russian artists featuring Siberian landscapes is on right now. Outside in the lobby area, a roomful of children are checkmating each other at the Alekhine Chess Club, which was formed in 1976. A large auditorium holds events and films screened under the aegis of the Eisenstein Cine Club run by Ghosh. He has in fact just wrapped up a memorial event for Gita Sen, filmmaker Mrinal Sen’s wife. “Sen had a great relationship with Soviet Russia. In fact, if he had been well, he would have spoken about Kolkata’s Russian connections. President Vladimir Putin had honoured him with the Order of Friendship in 2000.”

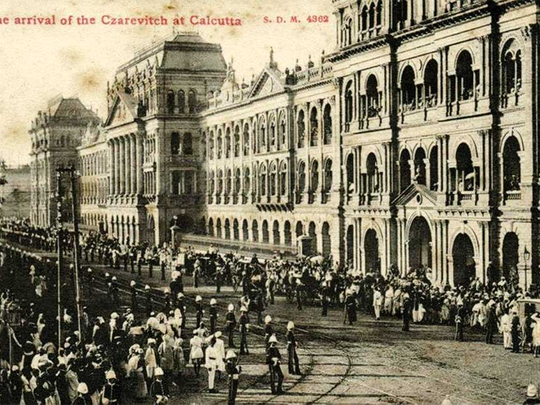

Kolkata has an interesting mix, a paradox of sorts, of influences that still exist from two ideologies that are poles apart. British imperialism and Soviet era socialism. So on one hand you have the old Brit club culture, the annual derby at the Race Course and other such ephemera which are enthusiastically covered by newspapers such as The Telegraph; and then there are the group theatres and chess clubs, the socialist thread running through the city’s marches and protests, the many people’s movements, the little magazines et al.

Many a conversation (or adda in Kolkata parlance) at roadside chai shacks still centres around the disappearance of Subhash Chandra Bose and his possible exile in the erstwhile USSR after the Second World War.

|

|

Addas — freewheeling conversations — in Kolkata’s old cafes linger on communist ideas and people still address each other as ‘comrades’ |

Chicken Kiev — the numero uno dish for Kolkatans with a love for ‘continental’ cuisine — is supposed to have been invented in St Petersburg in the early 1910s and resurrected in 1947 at a diplomats’ reception in Kiev.

Statues of Russian leaders such as Lenin, Gorky and Stalin are strewn around the city as are plaques and epitaphs; streets have been named after them. In a stroke of (perhaps unintended) genius, the erstwhile Leftwing government of the city renamed the street on which the American Consulate is located. Previously known as Harrington Street, it was changed to Ho Chi Minh Sarani (Avenue). As a result, all official communication from the American Consulate carries the name of one of American imperialism’s vanquishers. Putin would be having the last laugh now.

A pertinent reminder of the special relationship between Kolkata and Russia lies beneath its polluted, crowded roads, underneath which runs the Soviet-built Metro line with cool precision. Kolkata was the first Indian city to get a Metro line, with the help of Soviet specialists (and engineers from East Germany) who prepared a master-plan providing rapid-transit (metro) lines which connected the city of Kolkata in 1971.

Ghosh is one of the many avid lovers of the Soviet era in Kolkata. Like many in Kolkata, he grew up steeped in Russian literature thanks to the books his father would often bring home. “The idea of socialism attracted me as I was growing up. Their concepts of how society should be structured — their policies on education, health, housing and jobs. It seemed an ideal society to me.”

This is the one country which stood by India through thick and thin, says Ghosh — be it the 1965 war with Pakistan, the Goan liberation, the Bangladesh war. “And culturally too, Soviet Russia showed an abiding interest in the works of Tagore, Nazrul, Sukanta Bhattacharya, et al whose works were translated for Russians. “We discuss the many translations of Tagore’s works by Russians. In 1917, several translations of Tagore’s Gitanjali for which he had won the Nobel Prize for Literature, were simultaneously released, including those edited by future Nobel Prize recipient and writer Ivan Bunin.

“We Bengalis have so many Russia connections,” says Satyaki Manna. “For instance, we say gola for neck and they say gorla.” We are sitting inside Milee Droog, the new cafe which Manna has started inside Gorky Sadan. I have just ordered a basket of pirozhkis with a tall glass of dark coffee. Manna tells me Milee Droog — Dear Friend in Russian — is the first cafe in all of eastern India serving Russian food. The cafe menu lists khachapuris, blinis and syrinki, among other dishes. The walls have posters of Kremlin, and book cases full of Russian literature. Manna’s wife Irina Sergeyevna is from Russia.

The cafe has been decorated with handicrafts from Russia. Irina takes out a wooden lacquered plate in red, gold and black motifs. “This is a khokloma plate,” she says, talking about a well-known style of Russian folk art that derives its name from a village in Central Russia. The rich floral motif is made up of scarlet, black and festive gold colours (golden leaves and flowers symbolise a happy life and are believed to bring light and wealth).

Khokhloma is one of two wooden souvenirs that can be found in almost every tourist’s bag who returns home from Russia: The other is the matryoshka doll. And a row of the dolls sits on a shelf. “People mistakenly call these Babushka dolls. Babushka means grandmother! Matryoshka come from the concept of the mother, babies nestled inside a mama. Russia places emphasis on the matriarch, therefore the popularity of these dolls. Now they also do dolls with political figures!” she laughs. “I guess they have become a fad.” On another shelf, tins bearing distinctive blue and white work known as Ghzel pottery stand on the countertop along with the flags of Russia and India.

A few kilometres away from Gorky Sadan, near College Street in North Kolkata, located in a grey building in a narrow lane is Manisha Granthalay, a bookstore whose shelves stack hard-bound Russian classics and beautifully illustrated folk/fairytales, and children’s stories that an entire generation grew up on. The publication of these books stopped in 1991, the year the Soviet Union disintegrated. These are the last remaining copies.

The store is a slice of Kolkata history — it was inaugurated by Satyendra Nath Bose in 1964, their logo was designed by Satyajit Ray. Well-known artist Jamini Roy gifted an oil painting.

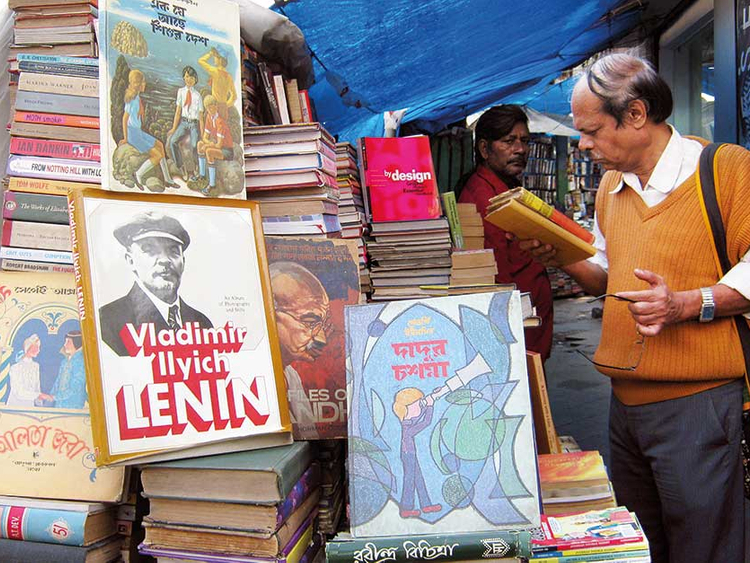

Across the city in South Kolkata is Golpark which is famous for its streetside booksellers. Book lovers know that they will find old and out-of-print editions among the rows of stacked books. This is a popular haunt for people looking to buy old Soviet era books. Most sellers have their stash of such treasures. One of them, Manik Sarkar, boasts of several editions of Soviet Literature journals selling at Rs100 (Dh5.39) each; an edition of the works by well-known Soviet agriculturist and plant breeder Ivan V. Michurin who died in 1935 for Rs300; and Russian 19th century Gothic Tales published by Raduga Publishers Moscow going at Rs200.

A regular visitor to these stalls, educationist Probin Chandra Ghosh has come looking to add to his collection of Bengali translations of Russian books. “These are now only available here, at some stalls at the Kolkata Book Fair and at CPI (M) stalls during Durga Puja,” he rues.

Ghosh grew up on Soviet era children’s story books. As did his son. He recommends the translations done by Noni Bhowmik and Arun Som who worked in Moscow as a translator from 1974 to 1991. Ghosh particularly likes his translation of Quiet Flows the Don by Mikhail Sholokov and Fathers and Sons by Turgenev. Soviet era books in Bengali are still popular going by the number of people still buying them or looking for them in book fairs. There’s also a blog — sovietbooksinbengali.com — that has scanned and uploaded many of these books.

Kolkata is also known for its Group Theatre — plays with a thread of political identity. A form that is influenced by the Stanislavskian school — most theatres in the city still host adaptations of writers like Chekhov. A grey stone plaque on Ezra Street bears the epitaph for writer, linguist and Indologist Gerasim Stepanovich Lebedev, who launched Bengali Theatre in November 1795, with a Bengali version of Richard Jodrell’s comedy The Disguise. Many historians consider this the first instance of a Bengali play on a proscenium stage in Bengal. Ezra Street was then known as Domatalla Street. W.H. Carrey in his book The good old days of honourable John Company, refers to the hall “...there existed in 1795, another theatre in Domatalla, in a lane leading out of Old China Bazar and very near to the other theatre.”

According to an article in StageBuzz about the growth and development of Bengali theatre between 1770 and 1880, Lebedev formed his theatre with the help of his teacher, Goloknath Dass. The players were Bengali and box tickets were sold for Rs8 and gallery for Rs4. He set up a Bengali company in opposition to the New Playhouse in Calcutta, which staged English plays for audiences of colonists.

Today, theatre connections continue between the two countries. Last year in June a Moscow-based theatrical group, the School of Modern Drama, took part in the international theatre festival in Kolkata. This was the first time a Russian repertory company was represented at the festival. The play was called Save gentleman of the bedchamber, Pushkin.

Anuradha Sengupta is a writer based in Mumbai, India