We moved to Dubai from Qatar seven years ago because of my dad’s job; he’s called Mark and he’s the Chief Financial Officer of Du, the telecom company. At first it was hard leaving my friends to come here, but now I love Dubai – I love the Middle East, and it feels great to be living somewhere that often seems like the ultimate holiday destination.

I like to spend time on the beach, at the cinema, going shopping with friends, all the normal things a teenage girl does, but the thing that has really taken over my life during the past few years is climbing. It started with a school trip when we went to Everest base camp when I was 14. It should have put me off for life – I was the only girl, I had very bad altitude sickness and we couldn’t shower for weeks – but somehow it was the best time of my life.

It was my first long trip away from home, it was in the middle of the beautiful Himalayas and it gave me the chance to forge fantastic, lasting friendships with my classmates.

I came back and I couldn’t stop talking about it, so much so that I got my dad to try climbing as well. Since then, we’ve done all of our climbing together.

After the Everest base camp trip, some friends gave me a book about the Seven Summits, which is a mountaineering challenge where you climb the highest mountain in each of the seven continents – Kosciuszko in Australia, Kilimanjaro in Africa, Elbrus in Europe, Denali in North America, Aconcagua in South America, Vinson in Antarctica and Everest in Asia. Only a few hundred people have ever done it because it’s such an enormous challenge and when I read the book I said to my parents that I wanted to do it, too.

I’m not sure anyone took me too seriously, but then in the summer of 2008 I went on another school trip to Kilimanjaro, the highest peak in Africa. My dad, who’s 49, came along after offering to be the extra guardian on the trip and we climbed to the top together. We had such a good time that we decided we’d go on to the next of the Seven Summits.

Climbing has completely changed our relationship – it’s been great having so much time together. It’s something most fathers and daughters don’t get the chance to do.

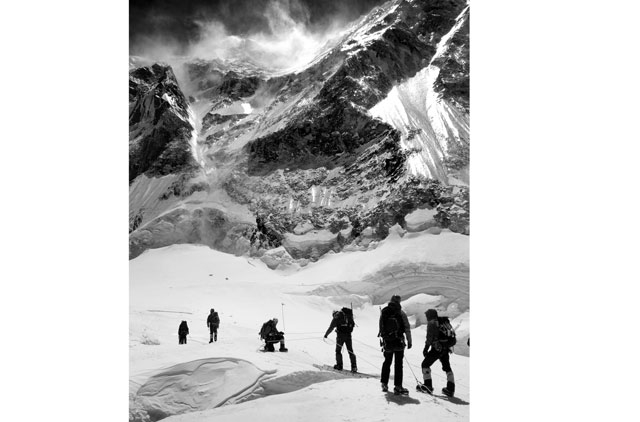

I became totally hooked on climbing after getting to the top of Elbrus in Russia, which took us a week. We then did Denali in Alaska, the highest in North America at 6,195m, which was our first seriously big ascent. It involved three weeks of climbing, carrying all our own equipment, and there was some tricky, technical climbing, too. It felt more dangerous than anything we’d done before and was the scariest climb we’d tackled – apart, perhaps, from the day we summited Vinson Massif in Antarctica last year, when the temperature dropped down to minus 58 degrees. We also made it to the top of Aconcagua, and Kosciuszko.

Then came Everest. We saved it until last because you need the experience, and it’s the biggest. Training in Dubai can be difficult because of a distinct lack of mountains, so we had to be a bit more creative, doing things like running up the stairwells of high-rises with bags on our backs, but most of the time – at least six days a week – we were in the gym near our home in the Green Community.

Because my mum, Jenny, and sister Kelly, who is 17, were joining us as far as base camp, they were training, too, and we all spent a lot of time on the step machine. We have one at home and the four of us were forever debating whose turn it was next.

We decided to climb for a cause

Everest was always going to be the big one – it needed two whole months to do. All the books I read about Everest were about the 1996 catastrophe where 15 people died, which didn’t make it the most appealing-sounding climb, but you find yourself going, “Well, that was 16 years ago, mountaineering’s come a long way since then,” and that’s how you deal with it.

We decided we’d climb for charity, and chose The Vitiligo Society because vitiligo is a condition that my mum suffers from. It’s where a person’s skin becomes lighter in patches because the cells which give skin its colour have become damaged or destroyed.

The whole family left Dubai on March 31, five weeks before my 19th birthday. We went to Kathmandu and then flew to Lukla in the Himalayas, from where our party began the two-week walk up to base camp at 5,500m. It’s all part of the acclimatisation process, and it’s one of my favourite parts. The scenery is beautiful, you start to get to know the guides and other clients and the walk up is really nice, although we all got coughs and colds and had every kind of weather, from sun to snow to hail.

At the back of my mind, I knew that I would soon be seeing dead bodies up there at the top. When climbers die, it’s difficult to bring them down and so there are quite a number of them scattered about, many of them having been there for years. You have to accept it as part of climbing Everest, and everyone climbing it knows they’re going to see them.

They’re almost a kind of warning about the enormity of what you’re taking on. For the time being, I tried to shut it all out, but there’s no getting away from the fact that they’re there, and the guides did talk to us about them so we were prepared.

Base camp becomes a second home

Base camp was huge, at least 500 people. You’re back and forward to base camp for the majority of the next few weeks, moving up to try to get used to the thinner air and then going back down to recover – you need to be properly acclimatised before you make your final summit attempt. After a while, base camp becomes like a second home, and by the end the tents there seem like absolute luxury compared to the higher camps. It feels like returning to civilisation with toilets and showers, even though the toilets are just barrels and very, very far from civilised.

When you climb up from base camp, one of the first obstacles you face is the Khumbu icefall, where there are ladders that stretch across about 25 terrifyingly deep crevasses. It’s very nerve-racking at first as some of them are 30m deep, and you know that to fall into one could be fatal. Eventually, though, as the initial fear subsides, you become quite quick at getting over the ladders.

As we went up and down the mountain during the acclimatisation process, it was amazing how quickly you could see changes in yourself. The first time we went up to camp two at about 6,500m, I felt absolutely awful. You curl up in your tent and feel your body shutting down; just getting out of your tent leaves you out of breath. But by the third time we went to camp two, the air there had started to seem quite thick. It’s amazing when you consider how horrendous it had seemed just a week or two before.

There were lots of people around, all waiting to make the final push to the top. They’d been delayed because the summit was fixed with ropes quite late this year, and you really can’t get to the top of Everest before those ropes are in place because climbers clip themselves to the rope to minimise the risk of falling off. What everyone up there now needed was a good “weather window”.

The first weather window was forecast to be on May 19, with a second one following on the 25th. That’s really late in the season to be making an attempt, so the majority of people all wanted to try to summit during the weather window on the 19th – about 175 people went up that day. We decided there were too many people trying it then, so we were going to try for the 20th, which was more of a gamble as the weather could turn.

We were the only team from the south side to set out that day: if we were to make it, we would have the whole summit to ourselves. We left at about 9pm, in the dark, by which time most people from the previous day’s attempt were back – although not all of them. We didn’t know that some people had died; in camp at 8,000m, you’re breathing oxygen from a canister, it’s incredibly windy and you can’t really hear anything. You just spend your whole time in your tent.

We had no idea that for some of the climbers things had gone disastrously wrong.

My mum and sister were back in Dubai by now, and luckily they didn’t know people had died up there until later, either, otherwise they would have been terrified, thinking it was us.

It’s so cold it can freeze your corneas

Conditions were awful when the 19 of us – seven climbers, four guides and eight Sherpas – set out: it was a case of trying to protect your eyes and put one foot in front of the other. It was dark, it was cold and it wasn’t fun. There was no pep talk because you can’t hear a thing. We didn’t take a break for three solid hours because it’s so cold you don’t want to stop: you just trudge up, almost like zombies. One of our team members’ corneas froze and he had to turn around and work his way down, blind, so that they could defrost.

It’s hard to describe how awful it is up there. Every step is a real effort, the weather was terrible, and when I saw the bodies of three people who had just died from the effects of either the cold or the altitude it was horrific. They were still clipped to the safety rope: you have to unclip and go around them. I was crying as I shuffled past.

It’s the kind of thing that haunts you every night. You end up thinking about their friends and family. It makes you concentrate on safety, too, and makes you think, “I don’t want that to happen to me.” It’s not so much, “There but for the grace of God go I,” it’s more of a worry that you might be next.

Worst of all was having to pass some people who were stuck and dying. We offered our help to them all. Our lead Sherpa checked everyone we passed, offering oxygen, water and even other Sherpas where he could. He helped to save a Chinese woman; we offered extra oxygen and Sherpas to a Korean team on a rescue mission – we tried to help everyone.

Up there above 8,000m it’s called the death zone, and your body’s shutting down. You’re dying yourself, and you know you have to get up and back down as quickly as you can.

Even though I knew that the only people we couldn’t do anything for were too far gone and beyond help – there’s no hospital to get them down to; it’s two days down steep ice and rock just to get to somewhere a helicopter can land – there’s no getting around how difficult or awful it was. It was the most horrific thing I’ve ever seen.

My dad and I were the first two people from our party to make it to the top. My dad was just in front of me so I made a big effort to catch up with him so we could walk on to the summit together. What was strange was that at almost exactly the same time, someone appeared from the other side, having come from the north. He took a photo of me and my dad, although we could have been anywhere as there were clouds all around and no view.

My dad and I gave each other a big hug and dedicated the climb to my granddad, who had passed away a few weeks before. But we couldn’t linger – it was still really cold, the camera quickly froze and I couldn’t open my water bottle because the lid was frozen shut. It was time to get down, and I was hit by the fact that we still had the whole of the descent to go, which on any climb is usually the most dangerous part because people often drop their guard, relax and make mistakes. Technically, too, the descent is often more difficult.

Still only barely below the death zone

When we’d descended a short distance to an area known as The Balcony, we suddenly had an amazing view, which is almost exactly the same as the view from the top, so we were pleased we did have something to look out across, and the image of all those mountains – we could see the tops of Makalu at 8,481m and Cho Oyu at 8,201m – will stay with me forever.

At high camp, from where we’d set off on our summit attempt the night before, there was a moment of, “Yes! We’ve made it back!” but you still have a very long way to go and you’re only barely below the death zone.

We had no idea it would be such a tragic season on Everest – we heard that six people had died in five days. Our motivation had simply been to complete the Seven Summits.

For me, it has always been all about the climbing, the lifestyle and the scenery; the challenge and the team. The tragedy was unexpected. My dad and I did talk about what had happened, all of the team did, and conversations went round and round in circles, all of us remembering things slightly differently thanks to the effects of altitude.

You still feel awful, and you know that the sooner you get down, the better, but we were able to get a message from there to my mum and sister who were very relieved and proud to hear that we were OK and that our only injuries were some frost nip and windburn.

It was only when we all got down to base camp that there was the realisation that we’d really done it and there were hugs all round.

The notion that I’m the youngest British woman to climb Everest and do The Seven Summits is only hitting me now.

We’ve also raised $90,000 from private and corporate donations for the Vitiligo Society.

I hope it will go a long way towards helping people like my mum who was very self-conscious and in need of support when she discovered she had the condition in her early 20s.

I think it will probably be years before I realise how doing the Seven Summits has affected the choices I make in life and how I face up to challenges. It completely shaped my late teens and has been such a big focus of my life that it’s going to be really strange not to have that any more. I hope mountaineering will always be in my blood, and the next thing I want to try are some technical, shorter climbs.

I start at University in Nottingham in the UK in September – I’m studying veterinary science – and hopefully I’ll be able to carry on climbing there. It might not be quite so dramatic, but even if there’s a climbing wall I’ll be happy.