Devendra Raj Mehta working miracles on a shoestring

How a retired civil servant and a craftsman helped change the lives of more than a million amputees

With his trendy henna-coloured hair and chiselled features, Danny could pass for a Bollywood actor. In fact he’s used to strangers staring as he flicks his locks and walks with a swagger. But Danny, 35, isn’t showing off – his gait is, in fact, because he lost his left leg and has only been able to walk since getting fitted for the Jaipur Foot nine years ago.

Before that Danny – whose leg was mangled from the knee down in a motorbike accident – could only move around with the help of crutches. He had no hope of walking independently until he heard of Bhagwan Mahavir Viklang Sahayata Samiti (BMVSS), a non-governmental organisation in Jaipur, India, that runs an artificial limb centre now famous for its cheap prosthetic device. Within hours of being measured for the Jaipur Foot – which costs just $50 (around Dh183) – he took his first steps. Within a day he was sprinting, riding a bicycle and even climbing trees.

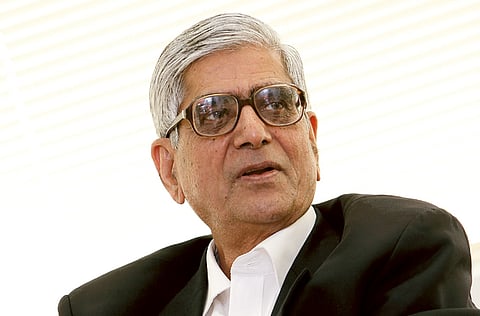

“He can run a kilometre in four minutes 35 seconds now,” says Devendra Raj Mehta, the founder and chief patron of BMVSS. “That’s pretty good by anyone’s standards, especially as he had given up hope when he came to us.”

Danny, who was unemployed, now works at the centre, helping the 150 or so people who queue for the Jaipur Foot every day after travelling to the centre from across the globe. They arrive on crutches, in wheelchairs or simply on the backs of their relatives, and leave on their own feet, usually within a couple of days at the most.

Changing lives

BMVSS has been changing lives with the prosthetic device, which can be attached to an artificial leg of any length, depending on where the amputation occurred, for almost four decades now. Every day it creates 150 customised legs of wood, plastic, rubber and aluminium almost on a conveyor-belt basis, keeping the cost to a fraction of the $10,000 (Dh36,730) spent on a prosthetic limb in the United States.

With 22 branches all over India, the organisation gives away the limbs for free and doesn’t charge for the fitting or the patients’ accommodation. It even supplies deserving candidates with bicycles or funds for setting up small businesses.

“It feels great to help all the unfortunate people who come here,” says Danny. The centre is the brainchild of 75-year-old Mehta, a civil servant who retired as the chairman of the Securities and Exchange Board of India. He had nothing to do with the invention of the original Jaipur Foot, but its popularity is a result of him making it available free of cost to anybody who needs it.

“I got the idea after my right leg was broken in 43 places in a car accident in 1969,” he says. “Fortunately I received the best treatment and my leg was saved. But the five months I spent in a hospital made me realise just how many poor people’s lives were being destroyed by amputations.”

This realisation propelled him to start BMVSS some six years later with government support. The Jaipur Foot was already in existence by then. It was invented in the Sixties as a collaborative effort by an orthopaedic surgeon, Dr PK Sethi, and a craftsman with just grade four education, Ram Chander Sharma – affectionately called Masterji – who taught crafts to patients in a local hospital. Masterji made the first limb out of wood, aluminium and rubber.

Best foot first

“The story of the Jaipur Foot is very interesting,” says Mehta. “It began when a World Health Organisation team came to Jaipur in 1966, and part of their work was to introduce prosthetic limbs in India. They displayed a model to medical professionals. Being a member of the SMS Hospital, Masterji was among them. He has always been interested in fabricating new designs and was intrigued why the prosthetic limb did not look like a real leg.”

Masterji couldn’t understand why the prosthesis could not be aesthetically appealing as well. “It didn’t have any toes and the sockets for the knees were very heavy,” says Mehta. “So he promptly set about remedying it. He made a

die-cast of the kind of limb he envisaged and went to Chukabhai, a person who used to repair his punctured bicycle tyres. He poured rubber into the dies and the first cast was made.”

Masterji showed his version of the prosthetic limb to Dr Sethi and his team. “Dr Sethi suggested some changes and guided Masterji in crafting the first Jaipur Foot,” says Mehta. “So it was the result of teamwork.”

The first piece, made of wood with aluminium sockets, was ready and began being made in 1968. But between then and the opening of BMVSS in 1975, fewer than 50 limbs were fitted on to patients, who crowded the hospital on hearing about this wonderful new invention. The reason was a lack of planning and vision, says Mehta.

By then Mehta had recovered use of his legs after the accident and was back at work as principal secretary to the then Chief Minister of the state of Rajasthan. He suggested that the state government should consider popularising the Jaipur Foot to make a difference to the lives of millions of disabled people.

The initial objections – lack of funds for a building and staff – were brushed aside by Mehta, who suggested using the ramshackle ambulance garages of SMS Hospital. His proposal was accepted and BMVSS was born. Mehta was clear about his vision. “Technology by itself cannot bring about change,” he says. “The Jaipur Foot was no doubt a technical marvel, but there were no processes to manage its delivery in large numbers.”

The first thing Mehta wanted changed was the approach to visitors. “It had to become human,” he says. “It was common for patients to arrive and have to wait for days for mere registration. These are usually the very poor who lost their limbs in the course of daily labour for employers who took no responsibility. They arrived penniless and hungry and were without shelter as they waited for days in hope of being fitted with a limb.”

The first practice he put in place was that registration must be done on arrival, around the clock. The patient would then be given food and a bed. “The patient and a caretaker are hosted until the limb is custom-fitted. And they walk out with dignity, with return train or bus fare in hand,” says Mehta. “No fees of any kind are ever collected. The whole service is free.”

The entire process has now been streamlined. “Once registered, amputees are measured and a custom-made cast is heated to 350 degrees and attached to one of several sizes of artificial feet,” Mehta says. “The Jaipur Foot is unisex and can be fitted on children as young as a year old. They’ll need new prostheses once a year until they’re five, then every two years while they grow.”

Ordered approach

There is an ordered approach to making the limbs. The amputee’s stump is covered with a knitted sock and a plaster of Paris mould is made. From this socket a plug is made, which is an exact replica of the limb. High-density polyethylene (HDPE) pipe is warmed and stretched over the plug. A vulcanised rubber foot is attached and suitable straps are provided to fasten the limb to the body. Fitting is usually on the same day and amputees learn to use it within a few hours.

“Recently a Japanese man who lost a leg in an accident came to our centre from Tokyo via Delhi in the morning,” says Mehta. “By 5pm the prosthetic leg was ready and he was on the plane to New Delhi at 6.40pm. The flight from Delhi to Tokyo left early next morning. In less than 24 hours he was out of the country.” There is no criteria for patients at BMVSS, says Mehta. “If you need a limb, or an arm, or even just callipers, you can come to us. Nobody is charged for the limbs or the treatment.”

The effect the Jaipur Foot has on its patients is instant. Ankur, 15, from Jammu in Northern India, went to the centre two years ago. The schoolboy had a congenitally stunted right leg. “His face was drawn and he refused to smile,” says Mehta. Once he was fitted with the leg and took his first few independent steps, Ankur couldn’t stop grinning. Now he’s always laughing and has even learnt to roller skate. “It’s almost impossible to get him out of the skates now,” says Mehta.

Producing the flexible, waterproof prosthesis at such low cost has involved cutting some rather ingenious corners. For example, the HDPE material used for the leg’s exterior is the same material generally used for making irrigation pipes. “It is very strong, you don’t need titanium for this,” says Mehta. “With our design, people can kneel, squat or climb trees, which isn’t possible with other designs.”

The foot is heavier than many Western prosthetics and has no attached shoe, allowing it to work better in mud, rice fields and on uneven ground. Its flexibility means it’s easy to sit cross-legged or kneel for prayer. BMVSS, which gets a third of its funding from the Indian government and the rest from grants and donations, has handed out 1.3 million limbs to date. “Last year we fitted 23,005 limbs,” says Mehta proudly.

Over the years the group has set up camps or permanent clinics in Africa, Latin America and Asia. “We’ve held more than 50 camps in 26 countries, including Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iraq, and now we are set to go to Libya,” says Mehta.

“We even held three camps in Lebanon some years back with the Indian Peacekeeping Force that was stationed there. “We also had some construction workers from Dubai who had lost their limbs in accidents and were sent to our centre to be fitted with limbs.”

Not resting on its laurels

While the Jaipur Foot is already popular, BMVSS is not resting on its laurels. “We are constantly upgrading it,” says Mehta. “We were the first organisation to use polymers in our prosthetics instead of aluminium, which is more expensive. Now the sockets in prosthetics the world over are made of polymers. The foot design has also undergone many changes. We now use micro-cellular rubber inside for the toes and natural rubber to cover it all. Now we are moving on to synthetic rubber, so it is stronger, less costly and more environmentally friendly.”

BMVSS collaborates with institutions all over the world to make improvements. “Earlier for above-knee limbs, the joint was very crude,” says Mehta. “We introduced the self-lubricating Stanford-Jaipur Knee, with a revolutionary new technology developed by Stanford University working with BMVSS. It was recognised by Time magazine as one of the world’s 50 best inventions in 2009.

“The best part is it costs only $20. It mimics the natural joint movement. It has already been fitted to 5,000 recipients. A titanium knee replacement is prohibitively costly – around $10,000 in the US.”

The BMVSS is also collaborating on projects with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), including a wheelchair-cum-hand-pedal tricycle for paraplegic and polio patients who can’t use both limbs. “It can be used on bumpy roads, especially in Indian villages where there are no paved roads,” says Mehta. “We’ve already produced 150 of them in India.”

Technical collaborations also exist with the India Space Research Organisation (ISRO) and other technical institutions in India. “The foot that allows patients to climb trees, was a result of their research into polymers,” says Mehta.

“They helped us design it and we have a memorandum of understanding with them. The only problem is its longevity – it lasts about a year. We are working to increase its life to at least three years. MIT, BMVSS, Dow Chemicals and the American Society of Mechanical Engineers are working on it together.”

He now plans to go beyond the foot. “There is a project to make a bionic arm, with the National Institute of Technology, Delhi,” says Mehta. “We also collaborate with the Northwestern University, Chicago. There are about 13 institutions that are helping us through research. So we are going to be a major centre of research in prosthetics.”

There’s little doubt that the Jaipur Foot has changed many lives. Mehta wants to make sure BMVSS will keep doing it. “Our aim is to provide succour to every person in the world who needs to stand on his or her own feet,” says Mehta, who’s won the prestigious Rajiv Gandhi Sadbhavana Award and the Padma Bhushan awards for service to society from the Government of India. “We’d like to go across the world and supply the leg to whoever needs it.”

And Danny is very confident that they will be able to do just that. He’s just got back from a trip to Mauritius, where he taught the techniques to local workers at a camp held there. “I want to go across the world,” he announces to Mehta. Mehta beams back at him. Both of them have no doubt that the Jaipur Foot is destined to continue making a difference.

Tell us the story…

Do you know of an individual, a group of people, a company or an organisation

that is striving to make this world a better place? Email us at friday@gulfnews.com or the features editor at araj@gulfnews.com