Brady Barr was staring at death. The herpetologist and conservationist, who’s also the host and star of National Geographic Wild’s popular wildlife show, Dangerous Encounters had crawled four-and-a-half metres down an aardvark burrow in South Africa to shoot footage for a documentary about snakes, when a cobra suddenly darted out of a corner hissing furiously.

“Crawling down an aardvark’s burrow is crazy dangerous because you don’t know who’s going to be home,” says Brady, who was in the UAE last week for the premiere of season six of his show. “You can run into hyenas and leopards. I was about 15 feet under ground, camera attached to my helmet, feeling claustrophobic and sweaty when I turned a corner and there’s a cobra, it’s hood raised, striking at me.”

He makes a whistling sound and gestures with his hands, simulating a cobra hissing and striking. “And what do I do? I just grab and throw it, but as soon as it hits the ground it darts back at me. I am on my knees, screaming, and the camera crew outside thinks I am dying, that a leopard has got me! “For about ten seconds I was doing this dance of death with a huge Egyptian cobra, which is extremely poisonous.

If it had bitten me it would have been fatal. Each time it leapt at me, I kept grabbing it and throwing it back. “Finally it stopped, raised its hood and stared at me – my face just inches away from its flickering tongue. I couldn’t turn around to crawl out because I was sure it would bite me if I moved. I was frozen with indecision. We were staring at each other for maybe 20 seconds.

Then I screamed to my crew to help who threw down a stick, and with that I was able to capture it by pinning its neck to the floor with the stick. But because it was moving vigorously I couldn’t hold it for long, and someone had to come down and pull me back up by my feet.” Brady was shaking all over. “If I’d been bitten I would have died, no doubt,” he says after a moment’s silence reliving the frightening incident. “That shook me up a lot.

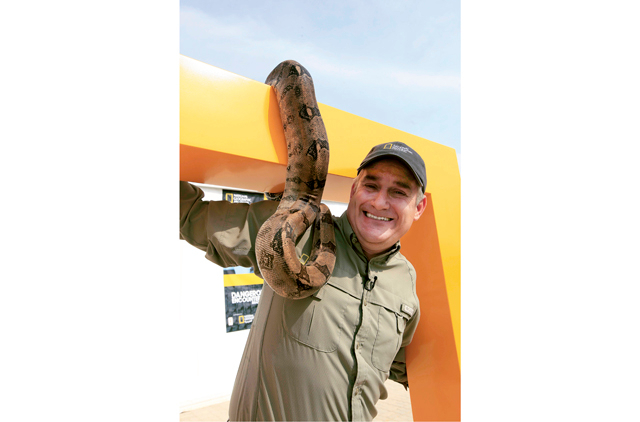

After that, I said I am not going to crawl down any more holes.” Situations like this are all in a day’s work for danger-loving Brady and, of course, that promise to himself lasted barely a few months. Brady, who will be 50 next month, has wrestled pythons, chased polar bears and ‘captured’ all 23 species of crocodiles in the course of creating jaw-dropping documentaries on wildlife in a television career spanning more than 15 years.

In fact, there doesn’t seem to be an animal that Brady isn’t willing to wrestle into submission in the name of research. He wants to learn more about each one and help prevent them from going extinct. “I have a wish list of animals I want to work with, and I’ve been marking them off,” says Brady. “Polar bears were at the top of it for a long time. I did that in the Arctic. Then the giant squid, and I managed that too. Right now it’s the walrus.

I’ve wrestled the giant octopus, giant squid, elephants, lions, grizzly bears, rhinos, giraffes, duck-billed platypus, venomous snakes, crocodiles, buffalos…” He’d like to work with all animals, except perhaps for bull sharks. “Bull sharks make me very uneasy, I’d never get into water with those,” he says. “They have a bad attitude.’’Brady, who’s hosted over 100 films for National Geographic – more than anybody else in its history – pays for his daredevil actions with nightmares.

“I pull muscles in my back and my neck all the time, and people ask me what happened. I am too embarrassed to say I pulled them during a particularly strenuous nightmare when I was back in the burrow fighting for my life, or under water fighting with a croc,” he says. “It scares my wife Maylene when she can’t wake me up. Yeah, I injure myself in my sleep.”

‘A thirst for knowledge’

What keeps Brady going back is, “a thirst for knowledge. There are so many questions about these animals, and I want them answered. Take crocodiles for instance, they are one of the largest reptiles on the planet but the scientific community knows very little about these animals. “There’s a lot more we need to know. So many of the animals are endangered, threatened with extinction. It’s a race against time.

We have to find out all we can about them to save to them, or we will end up just documenting their extinction. I love these animals, am passionate about them and want to learn as much as I can about them and educate the world.’’ To critics who question his methods of getting up close with animals to study them, Brady says, “National Geographic is all about real scientists researching real wild animals in their natural habitat. That’s why I’ve been there for almost 20 years.

I always include another scientist-researcher in my films. I don’t claim to know everything. What I do is science, and educating people about the animals. It’s not set up or fabricated. The bumps and the bruises, the bites and the broken bones are all real.” One of the most dangerous attacks he endured was when he was bitten by a boa constrictor while he was shooting a programme in a cave in Indonesia.

“It’s a very famous bite… It got international attention. It was a bad bite, but more than that, the setting was terrifying, inside a large cave on a remote island with a big boa constrictor wrapped around my legs, lots of bats …’’ Fortunately his team had an anti-venom injection, which saved his life. “What’s one of the most dangerous things about my job? It’s snake bites. Very often it’s not the snake bite itself that kills you. Rather it’s not being able to get proper medical attention in the nick of time.’’

Brady also seeks to dispel the myth that animal workers like him have no fear. “I am afraid on a daily basis,” he says earnestly. “I’ve lost friends and colleagues to these animals. Being scared is a really good thing, it keeps me safe, prevents me from getting complacent. You sneeze, or yawn or look away and you can be killed just like that. “Maylene worries about me a lot, but she also knows I am very careful,” says Brady. “She knows I am passionate about it, and it’s what keeps me going.

I have an eight-year-old daughter Isabella and a five-year-old son Braxton. They like animals. My house is already like a zoo; we have an alligator, a crocodile, ten snakes, scorpions, tarantulas, fish, salamanders, lizards and dogs. They are running a zoo whether I like it or not. It’s their’s not mine – the kids look after it all.”

Brady, however, is going slow these days. “The injuries are becoming more and more frequent,” he says. “I feel like I am 150. It’s hard for me to get out of bed some mornings, even tie my shoe laces. My reaction time is getting slower. The last three years I’ve been hospitalised many times, requiring surgery for injuries I sustained – snake bites, alligator attacks. I never used to get them earlier. I am getting older.

So I’ve slowed down a lot. I do more promotions, events with kids. I’ve left parts of my body all over the planet. I’ve broken my back three times, my femur, right arm, right wrist, lost a finger, cracked my left knee, had a lot of horrible injuries.” But more than all these injuries the tropical illnesses that Brady’s contracted over the years have put the brakes on his active participation in research.

“I’ve had horrible bouts of illnesses that science hasn’t been able to identify,” he says. “Once in Cambodia I got these worms in my system that travelled to my brain. They have not been identified so far. They clog the arteries in the brain. I had to have chemotherapy to kill these things on two different occasions.” Then there was the danger of malaria and Dengue fever. “I’ve had many friends die of it.

You can’t keep having anti-malarial drugs all the time. It’s bad for you. It’s not just cobras and crocodiles that can get you, it’s more likely the small things like these diseases and worms.” How does Brady’s work help? “Before you can protect an endangered species, you have to know as much about it as you possibly can.

How much space does it need to survive? What kind of things are affecting it? What is important in its diet? You can’t just protect the animal, you have to protect its environment too. That’s where I come in.”

The ultimate survivors

For Brady, reptiles are the underdogs of the animal kingdom. “It’s an interesting thought, but, yes, that could be true,” he muses. “If I was talking about warm and fuzzy animals like koalas or pandas you’d be throwing money at me. People love to protect the warm and cuddly animals of the planet.

You start talking about the cold and scaly snakes and people head for the exits. That’s why I try to clear the myths and misconceptions about these animals and educate through television. A third of the 23 species of crocodiles are endangered. And they are vital for the health of the planet.”

Brady’s interested in them because they are the ultimate survivors. “They have been around for 220 million years,” he says. “It’s a tough sell to convince people the cold and scaly animals are worth saving. It’s even more difficult when a crocodile or snake has killed someone. You have to be a pretty good salesman to talk to those people and convince them. And that’s where I come in; I’ve taken it on myself to be reptiles’ spokesperson.”

Brady uses the analogy of an arch’s keystone to point out their importance. “Every arch has a keystone that holds it up. Remove it and it collapses. Many species of reptile are what are called keystone species. If they become extinct the ecosystem can collapse,” he says. “Keystone species are important factors in the food chain.

Take, for instance, crocodiles. When they are small, they are a food source for other animals. When they grow up they regulate the population of other animals. Life becomes pretty difficult for human beings without the crocodile. “There are many places in Africa where people rely very heavily on fishing for their subsistence. Crocodiles regulate fish population; they eat undesirable fish.

So fish that feed humans are better and plentiful when crocodiles flourish. The rivers that run through villages where crocodiles have been hunted to extinction have fish that people can’t eat.” Brady had always been fascinated by reptiles. But he didn’t go straight from school to becoming a herpetologist. First, Brady taught school.

Later, while working on his PhD research on the food habits of alligators, he began pumping their stomachs to see what they eat. “I realised everybody was interested in what they eat,” he says. “So I took film crews to shoot this, and National Geographic was one of them. They thought I performed well and offered me a job travelling the globe, doing research.”

Brady does a lot of work with school kids. “I enjoy that the most; interacting with kids all over the world,” he says. “I talk to them about my job. It’s two-fold. I talk to them about how it doesn’t matter who you are if you are passionate about something and you follow your dreams anything is possible. I am a living breathing example of that.

The second thing I teach them is a strong conservation message to take better care of the planet, not just reptiles. So many are afraid of snakes. I like to show them they are not monsters, they are not going to attack you unless you intimidate them.”

But all talk of retirement flies out the window when you mention tigers. Brady’s eyes glint as he says, “Bring ‘em on, I say! I’d also love to do a film with tigers.” He leans forward, his face beaming, “I am up for any challenge.”