On January 15, 2016, Australian lawyer Philip Alston paid a visit to UN secretary-general Ban Ki-moon on his 38th-floor office at UN headquarters. Alston, the UN special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, was preparing a report that would castigate the United Nations for skirting responsibility for introducing cholera into Haiti more than five years earlier. If Ban hoped to salvage the world body’s good name, as well as his legacy, he had better move fast to right a historical wrong.

“It would be a great pity to go out on this note,” Alston said he later told Ban in what amounted to a thinly veiled warning.

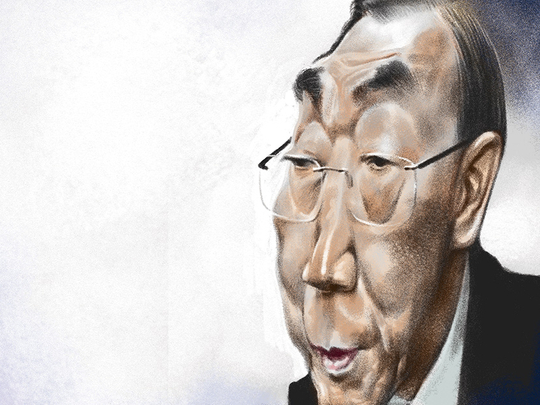

For a man weighing a likely run for the South Korean presidency, the hint of a potential scandal proved persuasive. Ban, 72, subsequently ordered a review of the UN’s response to Haiti’s cholera epidemic, which has killed more than 9,000 Haitians.

And so on December 1, after months of deliberation, Ban offered an extraordinary apology to Haitians on behalf of the UN, ending years of denials about the organisation’s complicity in the cholera epidemic. In a carefully crafted statement that acknowledged the UN’s moral, if not legal, responsibility, Ban said he was “profoundly sorry” and pressed UN member states to cough up as much as $400 million (Dh1.5 billion) to treat and cure Haiti’s cholera victims.

The effort marked the first stage in an intensive effort to shore up Ban’s legacy before he stepped down as the world’s top diplomat at the end of December.

Having endured a withering barrage of attacks on his leadership from his earliest days at Turtle Bay, Ban has notched some noteworthy late victories. He browbeat states into ratifying the Paris climate accord well ahead of schedule, and promoted equal rights within the UN bureaucracy and with conservative governments.

But the list of crises he leaves for his successor, former Portuguese prime minister António Guterres, is daunting. Syria is in free fall, North Korea’s nuclear arms programme is advancing, South Sudan faces the spectre of massacre, unprecedented numbers of refugees are on the run, and religious extremists are spreading terror throughout the globe. “We have collectively failed the people of Syria,” Ban told reporters at his final news conference on December 16. “Aleppo is now a synonym for hell.”

The organisation Ban set out to reform 10 years ago, meanwhile, is in many ways in worse shape than when he started, handicapped by great power divisions that have thwarted peace efforts from Syria to Ukraine and raised the spectre of a new Cold War between Russia and the West.

Ban’s UN has also been beset by self-inflicted wounds: a glacial personnel system that has confounded the efforts of United Nations peacemakers and staff missions. A broken patchwork of watchdog programmes that could not dependably root out corruption, expose sexual misconduct by UN blue helmets, or protect whistleblowers. And, indefensibly, the UN’s denial of responsibility for Haiti’s cholera epidemic.

“The most telling things about his legacy are the things he has the most control over, are the very things that have experienced some of the greatest failures,” said Bruce Rashkow, a former US and UN legal adviser who has championed UN oversight reforms since the early 1990s.

Critics also faulted Ban for lacking the qualities — charisma, intellectual agility and creativity — to make a great peacemaker. He has largely subcontracted mediation to a succession of special envoys, including former secretary-general Kofi Annan, to tackle peace efforts from Kenya to Syria. “Thank God he did delegate because as you can see, he is very weak on thinking on his feet,” said a top adviser. “That’s not his thing.”

Ban has bridled at the criticism, telling his aides that he has long been unfairly maligned by Western media because he doesn’t speak “Oxford English”. But his anger often got taken out on his subordinates: Ban frequently erupted into fits of anger when things went wrong at staff meetings or if he was being challenged by subordinates, leaving aides to keep their heads down to avoid catching his eye.

“It’s like when you’re told ‘Don’t look a bear in the eye, or he’ll think you’re challenging him’,” said one adviser.

Despite such setbacks, the story of Ban’s rise to the world’s top diplomatic job is as inspirational as it is improbable. At age 6, Ban and his family fled an offensive by North Korean troops, seeking refuge in his grandparents’ mountain home. Cut off from supplies and forced to endure bitter winter cold, Ban and his family survived on American handouts — rice, flour, powdered milk and hand-me-down clothing — and studied maths and science in books donated by Unesco.

Today, Ban still keeps an old, grainy, black-and-white photograph of himself as a boy with two younger brothers, a cousin and another boy; it reminds him of the hardships of his youth. They stand together in an apple orchard, stoic and joyless, their jeans patched, their shirts torn and tattered around the wrists. That experience gave Ban searing insights into the trauma and deprivations of war.

“Life was very, very hard at that time,” he said, recalling that local authorities once instructed the children in his village to come to the town hall to witness a display of large numbers of dead North Korean soldiers. “It was part of the anti-communism education. We had to see all these dead bodies. It was terrible.”

A model student, Ban finished at the top of his class in his elementary, middle and high school before embarking on a diplomatic career that mirrored South Korea’s trajectory from a broken postwar nation to a major industrial powerhouse in which he served as foreign minister.

As secretary-general, Ban retained the habits of that diligent student, reading stacks of talking points and briefing papers late into the night, underlining key passages in green, yellow and red markers. Ban prided himself on keeping a taxing work schedule and forgoing vacations.

In March, Ban’s staff urged him to take advantage of a four-hour break in his Middle East travels to tour Jordan’s Petra, one of the world’s most famous archaeological wonders. King Abdullah II Bin Al Hussein would be there to accompany the UN chief. But Ban declined. Instead, he arranged a visit with World Bank President Jim Yong Kim to see the Zaatari refugee camp on the Jordanian border with Syria.

Last month, in his wood-panelled office towering over Manhattan’s East River, Ban was busy packing his boxes for the move back to South Korea while reflecting on the next stage in his political future.

It’s hardly a secret that he aspires to become president of South Korea, where he has been long viewed as an undeclared front-runner. One aide said he was “1,000 per cent sure” Ban has been secretly laying the groundwork for a political race for more than a year — despite his frequent statements to the contrary.

But in recent months, an influence-peddling scandal back home has tainted the ruling Saenuri Party, which was expected to support Ban’s campaign. The controversy has fuelled calls for the resignation of South Korea’s conservative president, Park Geun-hye, and caused Ban’s poll numbers to slip for the first time behind the leading opposition candidate.

Ban said that he is “seriously considering” a run, suggesting he felt an obligation to lead his country out of a series of crises. The South Korean economy is buffeted by new economic headwinds and the prospects of the country’s first democratically elected leader impeached in disgrace. The election of US President-elect Donald Trump, who has raised questions about America’s commitment to its security agreements with allies, has introduced new uncertainty.

Ban acknowledged that there are serious hurdles to a successful campaign. The ruling party, he said, is on the verge of collapse, or splitting into two warring factions of Park loyalists and those who oppose her. Ban said it would be “extremely difficult” to start his own party at this late stage. But he said there is a move afoot to create a third party, presenting a possible platform for a Ban campaign.

“I’m becoming more and more serious now,” Ban said in a December 16 interview with “Foreign Policy”. “There are a lot of people asking for me to positively consider and work for the country. I have to be seriously thinking how best I should contribute to my country.”

“The Korean government and country is going through a very, very difficult situation in terms of change of administration in the United States,” he added.

Ban reflected on the strains of his UN tenure and voiced frustration with his efforts to prod autocrats, from North Korean leader Kim Jong-un to Syrian President Bashar Al Assad, to place the interests of their people above their personal ambitions for power. In the early stages of the Syrian war, Ban said he struggled to persuade Al Assad to enter a power-sharing pact with the country’s anti-government groups.

“There was no point speaking with him,” Ban recalled. “At the beginning of this crisis I spoke five times [to Al Assad], and each time he was lying. I was advised by my senior advisers, ‘Don’t speak to him, and don’t meet him’.”

The break came with a cost. Ban found himself with little leverage or influence over the Syrian leader, and tasked a succession of envoys to try to cut a political deal with Al Assad. “He was so tough about Bashar Al Assad that he dealt himself out of the game, probably to the mutual relief of both,” said a senior adviser.

In assessing Ban’s tenure, some observers noted that on matters of war and peace, from Syria to Ukraine, the secretary-general is largely only a figurehead — a cheerleader at best, but often a bystander to the decisions of the world’s biggest powers. However, Ban deserves credit for doggedly pressing from his first days in office for international action to limit greenhouse gases and helping usher the Paris climate accord’s swift entry into force in November.

“Climate is the crown jewel of Ban Ki-moon’s legacy,” said Bob Orr, a senior adviser for the UN chief, whom he credited in 2007 with persuading then-US President George W. Bush, a sceptical Texas oil man, not to derail climate negotiations. “He hauled climate change out of a ditch.”

Richard Gowan, a UN expert at the European Council on Foreign Relations, agreed.

Ban “had very little to show for himself at the end of the first term,” Gowan said. “He would probably have been written off as a C-grade secretary-general. Because of climate change, he will be remembered as a B-grade secretary-general. I think historians will quibble over whether his role was decisive. I don’t think you could say no deal without Ban, but he did put his shoulder to the wheel.”

His climate achievements are at risk under the incoming US administration. In his campaign, Trump dismissed global warming as a “hoax” perpetrated by the Chinese to hinder US industry. And he has threatened to withdraw from the Paris pact.

Ban said he pressed Trump during a phone conversation, three days after the November 8 election, to reconsider his position on climate change. Ban said Trump was mostly in a listening mode, but that he assured him he was keeping an “open mind”.

“I’m hopeful that as a successful global business leader, he will understand that business communities are already changing and retooling their way of doing business” to limit global warming, Ban said.

Ban’s rags-to-riches story has played well with American audiences. Like many of his generation, Ban has long viewed the US as South Korea’s protector and the natural leader of the free world.

As an 18-year-old student, Ban won a nationwide English-language essay contest that landed him a spot on an American Red Cross-sponsored visit to the US. It was during that trip that Ban and dozens of other foreign students were granted an audience with then-President John F. Kennedy. The meeting, Ban would recall, inspired him to pursue a career in diplomacy.

His diplomacy would bind him even closer the US. Ban would gain a reputation as one of the most pro-American officials in Seoul, pressing the Roh Moo-hyun government successfully to deploy Korean troops in Iraq as part of the military coalition led by George W. Bush.

The Bush administration favoured Ban, in part, because of his steadfast defence of the US-South Korean alliance. But Bush officials also appreciated Ban’s lack of the qualities that his predecessor, Kofi Annan, possessed — a charismatic bearing and a commitment to act as the world’s moral authority, including asserting that the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 was illegal. In his memoir “Surrender is Not an Option”, former US Ambassador to the UN John Bolton said the Bush administration wanted a chief administrative officer at Turtle Bay, not a secular pope. That Ban followed several years later contributed to his well-deserved reputation as the most pro-American UN secretary-general in history.

The Obama administration, which was eager to expand cooperation with the United Nations, initially found Ban wanting. Samantha Power, who would later become President Barack Obama’s UN envoy, dismissed Ban as an uninspired choice for the top UN job. “Is that all there is?” she asked a reporter from the British magazine the “New Statesman”, before Obama was elected.

But Obama administration officials warmed up to Ban, who proved to be a reliable ally on a range of issues from climate change to the promotion of equal rights.

“This advocacy did not come naturally to me,” he said in a November speech before the Elton John AidsFoundation. “I grew up long ago in a deeply conservative Korea.”

In a farewell ceremony before the UN General Assembly, Power praised Ban’s contributions to equal rights, and for investing “all of his diplomatic energy” in coaxing governments into signing the landmark Paris agreement on climate change and helping to see it brought into force “far swifter than any of us had thought possible”.

Ban’s public profile improved in his second term, and he displayed a willingness to speak out more frankly on human rights. He incurred Israel’s wrath in January 2016 by saying it is “human nature to react to occupation”. He also showed a willingness to back a more muscular approach to peacekeeping.

In the Ivory Coast, he instructed UN peacekeepers, backed by French forces, to participate in a rare military offensive that toppled then-President Laurent Gbagbo after he refused to accept the results of democratic elections.

When turmoil engulfed the Middle East, Ban rallied behind the Arab Spring’s protesters in several countries, infuriating the region’s autocratic leaders. “The flame ignited in Tunisia will not be dimmed,” he said. “The old way is crumbling.”

During his final year in office, Ban has taken forceful stances on a number of other fronts, excoriating the UN Security Council for its failure to halt mass atrocities from South Sudan to Syria. On November 1, Ban summarily fired a Kenyan general whose forces failed to protect civilians, in what one top aide characterised as the secretary-general’s final “mic drop” before ending his term. But Kenya’s government dismissed it as scapegoating. “The secretary-general, in lame duck season, seems to have found the courage that has eluded him throughout his tenure,” Kenya’s UN Ambassador Macharia Kamau told reporters.

But critics say Ban’s tough medicine has been unevenly dispensed, and that he has been unduly influenced by powerful countries. South Korea, Qatar and Saudi Arabia, for example, are among the states that contribute to a discretionary trust fund Ban uses to cover pet initiatives or travel beyond what his budget allows.

South Korea alone deposited about $1 million into the account this autumn to supplement Ban’s travel costs through the end of the year, according to two senior UN officials. But Ban instructed that the money be put into a separate account to fund cholera relief programmes in Haiti.

He has tended to tread lightly over the excesses of big powers such as China, remaining silent when Liu Xiaobo, a pro-democracy advocate who served 11 years in jail, received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010. Ban, who at the time was seeking China’s support for a second term, didn’t even bring up Liu’s case when he met with then-Chinese leader Hu Jintao.

Ban also yielded to pressure from Israel and Saudi Arabia to remove both countries from a blacklist of governments or armed groups that have killed or maimed children in the course of conflict. In a meeting in September with Egyptian President Abdul Fattah Al Sissi on the sidelines of the General Assembly, Ban neglected to respond to concerns about a crackdown on the press. Instead, Ban devoted the first couple of minutes of the meeting to presenting Al Sissi with a copy of a book highlighting his legacy. The briefing proved so awkward for Ban’s staff that they decided not to issue a standard readout of the meeting for the public.

Critics also say Ban was less than persistent in seeing through a raft of reforms aimed at rooting out corruption and transforming the UN into a more efficient institution.

The UN’s top political adviser, Jeffrey Feltman, complained in an internal e-mail that the world body’s effort to streamline its IT system was undermining its ability to pursue peace. And Anthony Banbury, an American official who headed the UN’s peacekeeping logistics unit, said the UN’s “sclerotic personnel system” normally required 213 days to hire a new recruit. But a new reform implemented in January 2016 was likely to extend that period to over a year.

“If you locked a team of evil geniuses in a laboratory, they could not design a bureaucracy so maddeningly complex,” Banbury wrote in the “New York Times”.

The UN’s internal oversight division, which is charged with rooting out waste and corruption in the world body, imploded under Ban’s leadership. An auditor he chose to run the oversight agency left after an independent panel accused her of abusing her authority by pursuing a senior Swedish human rights official who exposed the UN’s failure to respond to sexual abuse of children in the Central African Republic.

Ban also struggled to win the respect or loyalty of the UN staff, who contend he was in over his head.

From his early days in office, Ban’s ventures into personal mediation yielded few results and drew charges of coddling dictators. Ban also has long sought to play a role in ending the nuclear standoff with North Korea. But years of back-channel diplomacy ended when Kim Jong-un cancelled a May 2015 visit to an industrial centre in North Korea.

One UN official who served a stint as Ban’s note-taker recalled a typical exchange with a world leader: Ban would begin the conversation with a brief greeting in the native language; he would read directly from his talking notes. There was no small talk.

“On every phone call he would read off the talking points with virtually no deviation and make no attempt to build relationships or engage in small talk,” the official recalled. “Quiet diplomacy? He displayed no skills for that.”

The Haiti cholera epidemic continues to leave a cloud over Ban’s legacy. In October 2011, cholera-infected waste from the UN’s Mirebalais peacekeeping camp leaked into the Meille River, a tributary of the large Artibonite River, triggering an epidemic that still confounds Haitians.

In November 2011, lawyers representing 5,000 Haitian victims filed a petition for relief with the United Nations. It demanded a formal apology, compensation for the victims and a commitment to install a water and sanitation system capable of controlling the epidemic. The UN refused to negotiate a settlement with the lawyers on the grounds that its forces possessed diplomatic immunity from any claims.

A “veil of secrecy” has long hung over the UN’s legal decision to deny responsibility for the epidemic, a former UN lawyer said. It has fuelled conflicting theories about Ban’s role in the decision.

Several diplomats and officials close to the issue said the UN’s top lawyer, Patricia O’Brien, and the heads of the departments of UN peacekeeping and field support, Herv Ladsous and Susana Malcorra, initially prepared a memo indicating that the UN had an obligation to engage in discussions with the plaintiffs. According to this account, UN officials say Ban rejected the advice after consulting with the US.

But other officials said the strongest resistance came from O’Brien, and indirectly from the US, which would have to foot nearly 30 per cent of the bill for any payout of compensation.

The message from senior US officials in New York to their UN counterparts was “basically, you guys created this problem, you sort it out”, said one former senior UN official. “Don’t ask the US administration to go to Congress and ask for $5 billion to clean up this mistake.”

In the “Foreign Policy” interview, Ban largely evaded questions about his role in refusing to extend compensation to cholera victims, or to disclose the advice he received from the US and other big powers who feared the cost could reach into the tens of billions of dollars. The UN lawyers, he said, were very “strict” about not admitting responsibility for the crisis in the face of “legal attacks” by lawyers seeking billions in legal claims for Haitian cholera victims.

“We were very much defensive on this matter, it’s true,” he said.

O’Brien, who is now Ireland’s ambassador to the United Nations in Geneva, denied a request for comment. But her judgment that the UN had no obligation to compensate victims proved controversial even within the legal department. Mona Khalil, a UN lawyer at the time, registered her opposition to the legal opinion, citing unspecified “political interference”, according to the letter of resignation she tendered last year.

Khalil wrote that she had “explicitly reserved” her position on the legal judgment arising from the cholera epidemic in Haiti, while understanding “full well my duty to defer to the decisions of the leadership”.

In the end, Philip Alston welcomed Ban’s apology as an “important step in the right direction”, according to a December 1 statement. But he said Ban’s refusal to accept legal responsibility for introducing cholera into Haiti means that any compensation would amount to charity. “As a result, there remains a good chance that little or no money will be raised.”

Bruce Rashkow, the former US and UN legal adviser, also faulted the UN for stonewalling for so many years and refusing for more than six years to acknowledge its responsibility.

“Apologies are cheap. It’s the right thing to do, but it doesn’t take away the blemish on his legacy,” Rashkow said. “In fact, it reinforces the blemish.

–Foreign Policy/Washington Post