Squinting over my giant bump, I tried to make sense of the fuzzy black and white dots on the screen. “Not long now, baby,” I thought as the lady doing my scan asked if I wanted to know the sex. I glanced over at my husband, Barry. He smiled, and we both leaned forward, eager to find out. “It’s a boy,” she announced and excitement surged through me. We already had a three-year-old girl, Molly, at home.

A little brother would be perfect – the family Barry and I had always dreamed of. “Let’s go and buy something blue,” he said, holding my hand as the sonographer busied herself counting our baby boy’s ribs. “That’s his heartbeat,” she said as we saw more grains of black and white pulsing on the monitor. “He’s really strong.” Relieved, I smiled at her. It had been a long road to get here. I’d been diagnosed with polycystic ovarian syndrome years earlier. I had lots of cysts on my ovaries, making it harder to conceive.

It had taken two years to get pregnant the first time, but I’d miscarried at 11 weeks. Devastated, we vowed to try again and, luckily, after six months I’d discovered I was expecting Molly. This baby boy had been three years in the making and I’d had to take Clomid – a fertility pill. Now it was only two weeks until our son was born. “We’ll scan you again next week,” the sonographer said, and I nodded, ready to hit the shops with Barry. “Did you get any pictures?” he asked after we’d left the hospital, but I’d been too excited to ask. Still, we had the ones from our first scan. “Look at his cute button nose,” I said, taking them out. “He gets that from me.”

I went a bit mad buying little dungarees, tiny blue T-shirts and Babygros. “Aren’t they cute?” I said, showing them to Molly later. She nodded. “For my little brother,” she grinned, and we all began counting down the days. None of us could wait for the baby to be here, though I was dreading the birth. I’d needed an emergency Caesarean under general anaesthesia with Molly after being induced, and I didn’t want to go through that again. That’s why I guessed I was being so closely monitored at the hospital near our home in Ballinasloe, County Galway, in Ireland.

Each week I had all the antenatal checks and a scan. Every time I’d gaze at our baby, longing to hold him in my arms. “He’s never coming out,” I groaned as I went one, then two weeks over my due date. Then one evening, I woke up from dreaming I’d been fighting Mike Tyson and felt something pop. “Oh my gosh, the baby’s coming,” I shrieked. My waters had broken in the middle of the night. Barry’s parents rushed round to babysit Molly while we dashed to hospital. I was sure it wouldn’t be long now, but my contractions were mild, and kept stopping.

That night crawled by, and the next. Three days after my waters broke, doctors decided to perform a Caesarean. My mouth was dry as I was given a spinal block to numb me from the waist down. “Hold my hand,” I whispered to Barry as a giant, green screen was erected to stop us from seeing the doctors cutting open my tummy. The screen was so big it touched my chin and almost scraped the walls of the theatre. “Let’s meet your baby,” the surgeon said, and then I could feel a lot of tugging.

It seemed to go on for ages, and I glanced at Barry, scared suddenly, but then I heard a baby cry. Our son. I waited to be handed him, or to hear a doctor ask Barry if he wanted to take him. Nothing. Just silence. No one spoke. Our little boy’s wails filled the room. Fear pulsed through me. “We’re just going to check him over,” a paediatrician said, taking him into a back room.

'He’s been born with no hands'

It seemed ages before she came back with our baby wrapped up in a blanket so tight I couldn’t see any of him. “You have a baby boy,” she began. There was a pause. “But he’s been born with no hands.” Shock crashed over me, and kept coming in waves. I couldn’t speak, I couldn’t think. “What do you mean he’s been born with no hands?” I heard Barry ask. The paediatrician spoke softly, explaining that our baby didn’t have any hands, and that his arms stopped above the elbows.

A tear rolled down my face, but I didn’t feel anything. I don’t know if it was shock or drugs, but I was numb. “Come with me, and you can see your baby,” the doctor said to Barry, and I nodded. Our boy needed him now. I was still being stitched up, and afterwards the surgeon and anaesthetist came around the screen. “We’re really sorry for what’s happened to your baby,” they said. I nodded, unable to answer. “Did you take anything while you were pregnant?” I shook my head. “Of course not,” I told them, guilt tearing at me now. I didn’t smoke or take drugs. “I took Clomid,” I spluttered but the doctors shook their heads. “That wouldn’t have caused this,” they said.

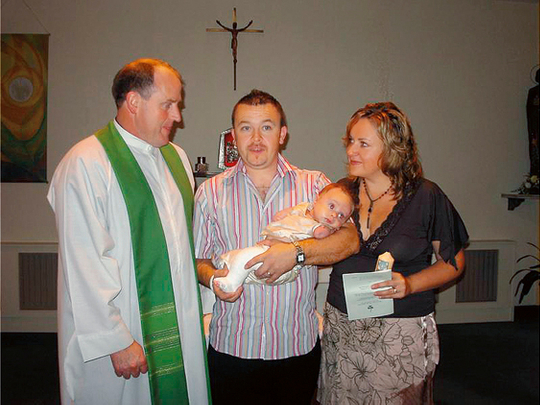

Now I was terrified everyone was blaming me. I wouldn’t do anything to harm my baby. I’d wanted him so much. Now I just wanted to see him. He was an hour old when he was brought to me in recovery. He was beautiful. He had the biggest blue eyes, and that button nose. “I love you,” I said, sobbing as I breastfed him. Afterwards, I steeled myself to look at him properly. His arms stopped before the elbow and at the end of the right stump was a full finger, while the other side had a squashed little finger that looked more like a thumb.

Already I loved him so much, but I couldn’t stop crying. It wasn’t huge gulping sobs, but silent sobbing, where tears just fell down my face. I was grieving for the child I’d thought I’d have, but who was now gone. Instead my Adam was here and he was so vulnerable that my heart was being ripped out of my chest. “I want Molly to be the first to see him,” I whispered. Barry’s mum Sandra brought her in. “You have a little brother, I told her gently, “but his hands didn’t grow.” Molly went straight over and kissed him. “He’ll be OK,” she smiled. “Look, he’s got a finger.”

It was hard telling our family, but they all supported us and Adam – and he was the most contented baby ever. He slept, fed and smiled right from the off. He needed an internal scan to check all his organs were fine, and luckily they were. Tests showed his legs were deformed though. He had a club foot and the right leg was shorter than the left. Also, his right leg was missing a bone, his little toe was missing and he couldn’t move his foot. He never cried though. As soon as I fed him, or held him, Adam would gurgle happily. Slowly, I accepted there was nothing I could do, and there was no point sitting around moping.

When Adam was a fortnight old, I decided to take him for a walk in his pram. So far only close friends and family had seen him. But when he was a couple of weeks old, I realised I had to go out. I covered him in a blanket and noticed people looking awkward when they saw us coming. Word had spread and no one knew what to say. Mostly it was people saying: “Congratulations,” without looking at him. Strangers were worse. “Isn’t he… oh no,” they’d say, shrinking back from the pram if they spotted his arms. One woman and her three children just gawped, open-mouthed, as I did the supermarket shopping with Adam – who had shrugged off his blanket.

I felt sick. How could people be so cruel? Out in the car park, I broke down. Poor Adam. It was always going to be like this. Over the next few months, I was amazed at how much our baby could do – and disgusted at people’s reactions to him. “Come away,” I heard one mum tell her children, when they spotted Adam in his buggy. “What’s wrong with that weird boy?” one child asked me as, horrified, I rushed away. My baby wasn’t a freak, something to be stared at. He was a gorgeous little boy whose arms and hands had never grown. That was hard enough – why should he be stared at and shunned too? “I want to move back home,” I told Barry one day. I come from Jersey, and my parents are still there.

I needed Adam to feel loved and secure. Not someone to gawp at. My grief had turned to anger. Not just at the callous strangers who thought it was OK to point and talk about my baby as if we were invisible, but at the hospital who had scanned me so many times. “They could tell me he was a boy, so why couldn’t they see he had no hands?” I’d rage. I went to see a solicitor but they said it could cost up to £40,000 (Dh232,150) to sue. I was a full-time mum and Barry was a chef. We didn’t have that kind of money. So we moved and focused on the future, not the past.

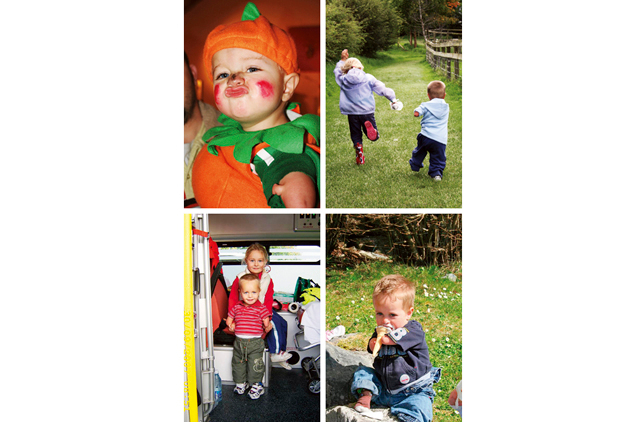

Doctors said Adam wouldn’t crawl but he shuffled on his bum. He learnt how to hold things between his stumps, and we had his club foot corrected. Because one leg’s shorter than the other, we had to get him fitted with a prosthetic for him to slip his leg into. We also got him false hands, which were basic with a pincer-movement, but he refused to wear them. He didn’t need them anyway as he can do everything just as well without them. Adam learnt to ride a bike with specially adapted handlebars. When we went to the park, he’d jump and go on everything, showing no fear.

At two, I decided to send him to nursery. I was scared he wouldn’t be accepted, but we gave the teacher pictures of Adam to show the children beforehand so they wouldn’t be scared. “Have a good time darling,” I said, kissing him goodbye. I cried all the way home. He loved every minute and had made loads of friends by the end of the day. One evening on the way home in the car, Adam looked at me. “Mummy, when will my hands grow?” he asked.

I gulped, trying not to cry. “They won’t ever grow, sweetie,” I had to say, “but it doesn’t stop you doing anything.” He knows we all think he’s amazing but I worry about when he’s older and he can’t drive, or get money out of his pocket to buy something – they’re all stupid things, but I’m his mum and I want him to be happy and do everything like other teenagers.

'I think he could do anything'

Adam is an outgoing, happy little boy who is at school now and loves football, trampolining and playing on his Playstation. He can type away using the pointy bone at the end of his stump and is better than anyone. He still hasn’t accepted that he’ll never have hands. Only a few weeks ago I heard him ask Barry, “Are my fingers under my skin, Daddy, waiting to come out?” That’s when I want to cry. Adam’s gorgeous but he does have a disability and no one wants that for their child. We’ll do anything to make our son fit in and Dorset Orthopaedic has made him special false arms with drum sticks at the end as he loves drumming. He says he wants to be a shopkeeper when he grows up, but I think he could do anything.

Now if people ask him why he doesn’t have any hands he tells them, “They didn’t grow when I was in my mummy’s tummy.” I registered Adam’s disability on the world-wide register as I’d been taking Clomid before I got pregnant. I was told that no other person in the world had ever had a baby with deformities after taking the drug, so we don’t know why Adam’s lower arms and hands didn’t grow. We never will.

Barry and I had DNA tests and nothing abnormal showed up but Adam faces a 50 per cent chance of having a child with limb deficiency. Right now though he’s more worried about reaching the next level on his Playstation and taking his trampolining certificate. He’s so talented, brave and happy, he’s an inspiration to me and a lot of others. I can’t ever feel down if Adam’s around. He’s only seven, but never feels sorry for himself or complains. He doesn’t have any hands but he has a big heart and even bigger grin – and that makes me proud to be his mum.

Juliette Dalton, 41, and her family live in St Helier, Jersey