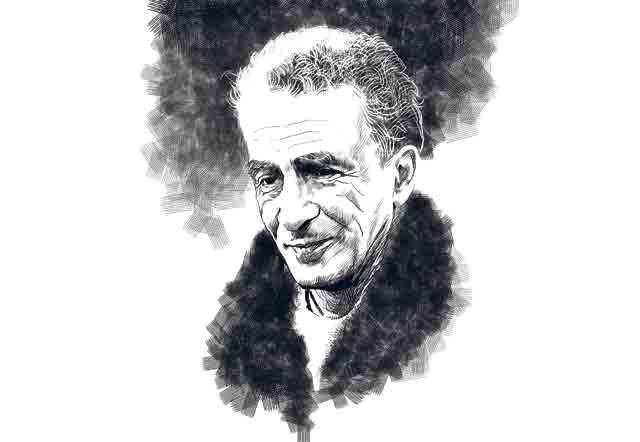

Few Arab novelists acquired the status of revolutionary hero as Kateb Yacine (1929-1989), whose 1956 novel, Nedjma (Nijma in Arabic) inspired Algerian revolutionary leaders.

Though Yacine wrote in French until the beginning of the 1970s, his work was instantly recognised as classic, as the poet and playwright delved into a "théâtre de combat" in vernacular Arabic, writing in a fiery but accessible language. This was not unusual for the time and, like several Algerian authors, including Mouloud Feraoun, Assia Djebar, Tahar Djaout, Kateb Yacine (his first name was always written after his family surname, which ironically meant "writer") wrote in French instead of using the Algerian dialect of Arabic.

Key developments would introduce a dramatic change and speaking in 1966, the author declared: "The use of the French language is to serve a neocolonial political machine, which only perpetuates our alienation. Yet the usage of the French language does not mean that we are the lackeys of a foreign power and I write in French to tell the French that I am not one of them." A child of colonialism, the revolutionary author aimed to inspire and mobilise and, as such, succeeded better than most.

Nedjma, the masterpiece

Yacine's masterpiece, named after his cousin whom the author loved but could not properly court, started out as a long poem, in which the character of Nedjma was a substitute for Algeria. By the time the poem was developed into an epic novel and published in 1957, the mysterious spirit was transformed into a quest to restore Algeria in a mythic manner.

Relying on modernist techniques and using multiple narrative voices rather than traditional chronological descriptions, Nedjma influenced francophone North African literature and many writers in developing countries. Yacine himself admitted that William Faulkner was the most important influence on his style of writing.

The story is set in Bône, Algeria, under French colonial rule. Though difficult to follow, the plot revolves around a beautiful married woman, who is loved by four revolutionaries, representing the four seasons. Nedjma, which means "star" in Arabic, never changes although the four revolutionary characters undergo dramatic transformations. Like Nedjma, the author underscores, Algeria can be discovered, although the more one engages its beauty, the less one really knows her.

In other words, our heroine is otherworldly, as she draws succour from her traditional clannish sources and as she incorporates local legends and popular religious beliefs into her actions. This theme, which focused on colonisation and alienation, filled most of the author's works. It expressed the Algerian tragedy as outsiders trampled the values of Arab civilisation. A later novel, Le polygone étoilé (1966), introduced several characters from Nedjma and, as the author himself explained, everything he has done constituted "a long single work, always in gestation".

In Paris after 1959, Yacine forged close ties with Mohammad Issiakhem and in 1954 had a meeting of minds with Bertolt Brecht. His play The Encircled Corpse, which was published in the influential magazine Esprit in 1954 and produced by Jean-Marie Serreau, so irked French authorities that the latter quickly slapped a ban on it within days of its first production.

Throughout the period when the Algerian liberation movement gained momentum, Yacine was hounded by the French police, especially the notorious Direction de la Surveillance du Territoire, which forced him to be on the move, hiding in safe houses throughout Paris.

If the open warfare against French rule ended in 1962, when Algerians gained independence, Yacine's efforts were not always appreciated. Like most intellectuals who inspire politicians, Yacine wanted ordinary men and women to be free, without falling under the dictates of power. Nedjma glorified Algeria but in a critical 1971 play, written and produced in Arabic, Mohammad, Carry Your Suitcase, the author portrayed the class complicity that existed between French and Algerian bourgeoisies. What increasingly irked Algerian revolutionaries was the writer's direct prose that reached millions. The revolutionary writer, he once remarked, "must transmit a living message, placing the public at the heart of a theatre that partakes of the never-ending combat opposing the proletariat to the bourgeoisie". Even for revolutionary Algeria, this was way too critical, as authorities became wary of their "hero".

Amir Abdul Qadir

Though Yacine's words disturbed many, they fell in the post-1830 Algerian mould when French colonial domination supplanted Ottoman rule, championed by the young Yacine's idol, the Amir Abdul Qadir. Yacine wrote several essays on how the Amir assumed power as he gained the loyalty of key tribal leaders to organise a rebellion against the French. What resulted was a relatively effective guerrilla warfare, which scored significant victories until 1842. Abdul Qadir was a gifted political and military leader but he also understood that the reason why Algeria was conquered was due to the refusal of the Kabyles, Berber mountain tribes, to align with Arab tribes against the French. This, he wished to correct, which so fabulously inspired the young Yacine and that can be seen throughout Nedjma.

Parenthetically, when Abdul Qadir lost against the more powerful French and after he was denied refuge in Morocco, he took up residence in Bursa, moving in 1855 to Damascus where he studied theology and philosophy. When the 1860 "conflict between the Druze and Maronites of Mount Lebanon spread to Damascus and local Druze attacked the Christian quarters, killing over 3,000 persons", Abdul Qadir and his "personal guard saved large numbers of Christians, bringing them to safety in his house and in the citadel". Paris bestowed on him the Grand Cross of the Légion d' Honneur and American president Abraham Lincoln offered him several guns, which are now on display in the Algiers Museum. Yacine noted these actions in his own essays to inspire others of what Muslim tolerance was all about.

The politically engagé lyricist

Beyond Abdul Qadir, and by his own acknowledgment, Aeschylus, Rimbaud, and especially Brecht, whom he met in Paris, inspired Yacine. Awakened to the many needs of his nation, he quickly broke with the establishment, concentrating on the public at large, which was largely illiterate at the time. This was the chief reason why he focused on political theatre and, towards that end, was probably inspired by Federico García Lorca, the renowned Spanish poet, dramatist and theatre director.

Writing in Afrique-Action in 1961, Yacine described how García Lorca returned from New York with a masterpiece play, the Romancero Gitano, which was quickly acclaimed throughout Spain. Still, García Lorca was not simply satisfied with writing and publishing a play; he applied and received a state subvention for a travelling theatre company that moved from city to city to bring to life the ancient Spanish theatre. This, Yacine reasoned, would be his calling too.

After 1970, Yacine produced some of his most political controversial plays, starting with The Man in Rubber Sandals, in which his Vietnamese hero was none other than Ho Chi Minh. There was a variety of small roles in this dramatic piece for Mao Zedong, Chiang Kai-shek, Pierre Loti and Marie-Antoinette, with a series of vignettes highlighting "the military history of Vietnam and the plight of the transient Algerian labour force in Europe".

Amazingly, the author pitted various characters against each other, the French opposite the Vietnamese, the Viet-Cong opposite the Americans, concluding with the trial of an American called Captain Supermac.

Needless to say, the author was opposed to the war in Vietnam and strongly objected to the post-1967 bombings of the North, which he witnessed first-hand. Yet, what was new in Yacine's play were his abilities to relate those atrocities to the plight of Algerians, still struggling five years into their own independence.

One of the greatest writers of the 20th century, Yacine resisted colonialism just as strongly as he objected to the adoption of narrow nationalism, especially if that was modelled to serve a privileged elite that wrapped itself in the flag.

He categorically rejected cultural domination, believing that such categorisation was unbecoming when men and women across cultures were tied with socio-economic elements ranging from freedom and equality to justice and wealth.

Yacine admired and wrote about Abdul Qadir at 17 but added value throughout his career by inspiring every single Algerian revolutionary leader.

Though most of those officials chose to distance themselves from Nedjma's author, Yacine stood with his people. At the height of the 1988 repressions and though advanced in age and in relatively ill health, he expressed anger at the political establishment that distanced itself from the Algerian people.

Unlike most, he at least knew who was authentic, anxious to serve rather than dominate.

Biography

Yacine Kateb was born on August 2, 1929, in Condé-Smendou, near Constantine, to Mohammad and Jasminah Kateb. His father's multicultural upbringing, both as a Muslim Algerian and French, spilled on to the highly literate family and the young Yacine was raised absorbing Arab achievement and the legends of Algerian and French heroism. After Quranic school, the young man entered the French-language school system at the Lycée Français in the city of Sétif.

Barely 15, he participated in the 1945 Sétif demonstrations when citizens protested unequal conditions, as the young man was arrested. Regrettably, the Sétif demonstration turned to rioting when the police and the army killed thousands of people. Yacine's imprisonment, without trial, was his first education of colonial injustice. Though he was freed a few months later, Yacine discovered two great loves in prison: revolution and poetry. In fact, he wrote one of his best-known sonnets, ‘La rose de Blida' (1963) in jail. The poignant poem depicted the author's mother, who thought that her son was killed in the Sétif demonstration and who consequently suffered a mental breakdown.

Upon his release and because of his "record" Lycée doors remained closed, which promoted him to move to Annaba and, from there, to France. He published his first novel, ‘Soliloques' in 1946 when he is barely 17 but returned to Algeria in 1948 to work for the ‘Alger Républicain' daily. By 1951, and in between odd jobs, Yacine travelled extensively through Italy, Tunisia, Belgium, Germany and reached Saudi Arabia, Sudan and Soviet Central Asia. After 1952, he devoted himself entirely to writing but was forced to leave France in 1955 because of his extensive involvement in the Algerian nationalist struggle for independence. On his return from Saudi Arabia, he published under the pseudonym Saïd Lamri a scathing attack on how the holy city of Makkah was run.

Yacine returned to Algeria soon after independence in 1962 and restarted writing in ‘Alger Républicain'. Between 1963 and 1967, he visited the Soviet Union and several Eastern European countries, while writing furiously. He visited Vietnam in 1967, which was also the year he stopped writing novels, to produce one of his most engagé plays, ‘The Man with the Rubber Sandals', written and first presented in Arabic in 1970. After that date, Yacine wrote in Arabic, focusing on popular theatre, often of the satirical variety and almost always in dialectal Algerian Arabic to communicate with his readers. Sadly, his plays bothered Algerian authorities, who confined him in 1978 to the city of Sidi-Bel-Abbès where he was barely allowed to run a minor regional theatre group. Banned from television appearances, he concentrated on schools or private companies and increasingly, evoked Algeria's Berber culture and the Tamazight language. In 1988, Yacine moved to Vercheny in France and visited the United States but died in the French city of Grenoble on October 28, 1989. Yacine had three children: Nadia, Hans and Amazigh.

Bibliography

- Soliloques, 1946

- Abdelkader et l'indépendance algérienne, 1948

- Le cadavre encerclé (The Encircled Corpse), 1955 (prod. 1958)

- Nedjma, Paris: Edition du Seuil, 1956, reprinted by Points roman, 1981

- Le cercle des représailles (The Circle of Reprisals), Paris: Edition du Seuil, 1959

- La femme sauvage, 1963 (play)

- Le Polygone étoilé, Paris: Edition du Seuil, 1966

- Les ancêtres redoublent de férocité, 1967 (play)

- L'homme aux sandales de caoutchouc (The Man with the Rubber Sandals), Paris: Edition du Seuil, 1970 (anthology of plays)

- Mohammad prends ta valise (Mohammad, Take Your Suitcase), 1971 (first published in Arabic)

- Saout Ennisa, 1972 (first published in Arabic) La guerre de 2000 ans (The 2000-Year War), 1974, (first published in Arabic)

- Le Roi de l'Ouest (The Western King), 1975 (a highly critical essay on Hassan II)

- La Palestine trahie, 1972-1982, (first published in Arabic), 1983

- L'oeuvre en fragments, Paris: Edition du Seuil, 1986

- Le poète comme un boxeur: Entretiens, 1958-1989, 1994

- Minuit passé de douze heures: écrits journalistiques, 1947-1989, 1999

- Boucherie d'espérance: Oeuvres théâtrales, 1999

- Un théâtre en trois langues, 2003