Earlier in July, the German chancellor Angela Merkel took a short break from the tortuous eurozone negotiations over the resolution of Greece’s financial woes to travel to the Balkans in a mission to strengthen ties between Germany and the region.

Her first stop was Albania, where the country’s Prime Minister, Edi Rama, welcomed her with all the usual diplomatic fanfares (it was Merkel’s first visit) — and an extra surprise.

While on her way to a press conference in the entrance hall of the prime minister’s office, an imposing communist-era building in central Tirana, Rama took Merkel inside a small room, where she was introduced to some of the most eminent European contemporary artists of our time.

There was France’s Philippe Parreno, best known for his film, made with Douglas Gordon, on the French footballer Zinedine Zidane; the Stockholm-based artist Carsten Holler, the subject of a solo show at London’s Hayward Gallery at present; the Albanian-born Anri Sala; the British conceptualist Liam Gillick; and Merkel’s compatriot Thomas Demand. The meeting, the artists said later, was awkward, and a little “surreal”, according to one of them.

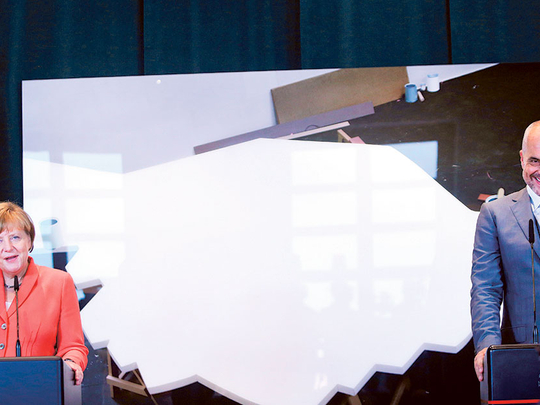

Inside the press conference, the two leaders gave their addresses in front of a giant photograph by Demand, called “Sign”, showing a model of a handshake, based on an actual sign used in the New York World’s Fair of 1939. That was an event that symbolised the optimism of a world that trusted in the future. But the sign, in the photograph, is unfinished, a couple of buckets of paint resting on either side of it. The handshake is a work in progress. Building a better world for tomorrow, Demand’s picture suggests, is not a straightforward business.

Outside the building, there were a couple of more nuanced messages for Rama’s distinguished guest. One of Holler’s famous mushroom sculptures, “Giant Triple Mushroom”, is a 3D collage of three different fungi: one edible, one poisonous and one hallucinogenic. The sculpture, said an official handout, “can be perceived as a comment on Albanian politics”.

At the entrance, a bright white marquee with flashing lights, designed by Parreno, welcomed visitors with an unmistakable touch of glamour. It signalled a new life for the building that was for so many years the muffled, sinister headquarters of the country’s hardline communist rulers. Today, it was being inaugurated as Tirana’s new Centre for Openness and Dialogue. And Rama, artist-turned-politician, was showing one of the planet’s most powerful leaders that nothing, in his view, can change the world quite like art.

The following day, I am ushered into Rama’s private office. The wallpaper consists of a series of colourful, abstract splurges against a white background. “They are my doodles,” he explains. Before he turned to politics, the 51-year-old prime minister was a practising artist, having studied at Tirana’s Academy of Arts, and he lived and worked in Paris for several years.

Fittingly, this is like no other politician’s office I have ever visited. There are boxes of crayons on just about every available surface in the room, and light orchestral music plays in the background throughout the course of our interview.

In one corner, there is a basketball on a hat-stand — Rama, who is 6-foot-6, also used to play for the Albanian basketball team. He is dressed in an elegant suit and sports a fashionably close-cropped haircut, which is roughly the same length as his salt-and-pepper stubble.

He is palpably proud of his new centre: he says it will attract people who may want to attend workshops on subjects such as, say, leadership. “But the art will be there. And I am sure that, next time, some of those people will come to see the art: ‘OK, I am going to see what is happening there.’ It is an interaction, which will make the space much more lively, more human.”

The art comes first, he says. “In my opinion, art first happens, and then all the talk about it happens. It is not that Carsten Holler needed Albanian politics to help him make the mushroom; he invented the mushroom, and then [it was applied] to Albanian politics.” The centre, he specifies, is not a cultural centre. “It is a public space where culture, politics and art can happen, all together.”

Inside the new venue, which is free to the public, there are further surprises. A small room houses seemingly random collections of artefacts from Albania’s communist years. They come from warehouses full of unused stock, from small household items to agricultural tools. A disorganised pile of sickles lies on a shelf. “As soon as I saw them, it made me think of the old flag,” says the display’s curator Edit Pula, another artist. She wants the room to create a “dialogue” between Albania’s past and future.

Another conversation takes place in the room next door: thousands of images dating from the end of the Second World War, newly digitalised and screened on two walls. One projector shows scenes from everyday life, the other focuses on official events. The audiences for the two have their backs to each other. Public and private life are kept apart, just as in the old days.

This is an ambitious project, I tell Rama: he is using the exploratory and experimental language of contemporary art to shed light on Albanian history and politics. “Languages are different,” he says slowly. “And to pretend that politics should speak the language of art might be misleading. But, at the same time, I think that art can exercise an influence, without really making it seem like a straightforward influence.”

He begins to tell me a long story about his grandmother. She was particularly proud of her kitchen, in which hung a painting by her brother-in-law, a famous Albanian painter who worked in a “very classical, realistic style”. One day, Rama’s father came home, bringing a painting by a friend, in a very different style: “like a combination of Cézanne and Georges Braque”.

“He replaced the painting in the kitchen, and my grandmother was outraged,” recalls Rama. “She said, ‘For all of you, the kitchen is relatively important. For me, it’s all I have. I wake up and I go to the kitchen, I spend my day in the kitchen. It’s totally unjust that you impose like this in the only space that I have!’”

The new painting, nevertheless, took the place of the old one. “Then, a few years later, my father wanted to change it again,” says Rama. “This time he brought a still life with flowers. And my grandmother was outraged again. My father said, ‘What’s wrong with you? You were revolted by the modern painting!’ And she said, ‘Yes, I was, but we have learnt to live with each other. I am in my place, and the painting is in its place.’”

This is the magical power of art, believes Rama. It can change you, even if you don’t realise it. “Which is not the case with propaganda art, which lets you know that it wants to influence you. Free art influences you without letting you know you are being influenced.”

Rama came to power in 2013, when his socialist party won a landslide at the expense of the former Prime Minister Sali Berisha, whose centre-right Democratic Party had ruled for eight years. In the years since the fall of the country’s communist dictatorship in the early 1990s, Rama had first pursued his career as an artist in Paris and then returned to his homeland, tucked in the volatile southeastern corner of Europe, to be appointed minister of culture in 1998.

In 2000 he became mayor of Tirana, and his thoughts on the transformative power of art were soon put to the test, when a series of buildings in one of the city’s neighbourhoods needed repainting. Rama decided that, rather than emulate the uniform grey dictated by communist edict, he would order the buildings to be painted in bright colours.

On the first day of work, he received a call from a supervisor on the site. “He said to me, ‘Mr Mayor, please help me, it’s a disaster, there are about 200 people outside, some are screaming, some are shouting, some are laughing.” Rama went to the site. He became embroiled in an argument with a representative from the European Commission, who disapproved of his plans.

Rama impersonates the distressed official: “I am going to block the project! We have never spent European taxpayers’ money on shiny colours for buildings!” Rama said he would have to spend his first press conference as mayor comparing European conformity laws to the dictates of communism. “So then he suggested a compromise. But I said all compromises are grey, even if you put primary colours together.” Rama re-enacts the conversation with gusto, and no little dramatic flair.

“Finally it got through. And it became a big, big, big thing. For two or three months, the main issue that was discussed in this city, and this country, was colours. And it became the first debate about the public interest that was not about politics.” Rama’s approval ratings shot up. “Colours made me very popular,” he says drily.

I ask if that was what he had been hoping for. “No, not at all! But my instincts told me it was the right thing to do.” His instincts were proved right in a series of extraordinary developments, he says. People living in the neighbourhood starting taking down fences and security grids from windows. “I asked them why, and they said it was because it was safe now. It showed me how improving public space could increase the capacity of people to cooperate with each other, to protect what they have, and maintain what they have.”

The most interesting revelation was yet to come, however. The discussion over the colours prompted Rama to hold a survey of opinions. Residents were asked two questions: whether they liked the colours, and whether they wanted the project to continue. Sixty-three per cent answered that they liked the scheme; but a greater number, 85 per cent, said that they wanted it to continue. “And that’s the connection with my grandmother’s story,” says Rama with a flourish. “If you asked her if she liked that modern painting, she would have said ‘no’. But asked if she wanted it taken away, she said, ‘no, leave it there.’”

Rama says the painting experiment taught him that aesthetics could have a telling impact on social issues. “Angela Merkel told me, after she saw the centre, that one of the most horrible things about communism was that, even through art, it never promoted taste,” he says. “Once you promote taste, you are promoting a higher quality of living, a higher understanding of citizenship, and duties.”

About half an hour from the centre of Tirana, there is an underground bunker that was built in the early 1970s to protect the country’s leadership in the case of nuclear or chemical attack. It is an extraordinary space of more than 2,500 square metres, consisting of five floors, 106 rooms, one-metre-thick concrete walls and even a purpose-built theatre. There is also a small flat, which was reserved for the leader, the notorious Enver Hoxha. He never stayed there.

Rama, who has opened the bunker to the public, believes that coming to terms with their past is a more complicated business for Albanians than merely listening to the unsavoury incidents of recent history. “It has been very difficult for us, to deal with the past in a way that is freed from the mechanisms that the past created for us to deal with the past,” he says, smiling at the convolution.

The bunker was opened, he says, “to give people the possibility of experiencing the past in a physical way, without the mediation of politics, or history, or sociology”. That applies especially to the younger generation, he adds. “I told my son things about communism but all I can tell him does not teach him as much as what the bunker taught him in a half-hour visit. Because it was physical. And then he came back to me and said, ‘Tell me more.’”

Rama’s approach to the synergies between art and politics has made him something of a cult figure among contemporary artists. Both Parreno and Holler, major players on the contemporary art circuit, donated their works to the new centre and they speak glowingly of the prime minister’s open-mindedness. I ask Rama if he thinks more artists should go into politics. “I don’t necessarily think that artists can be great politicians,” he replies. “But I am absolutely sure that politicians could do much better if they paid more attention to artists, and people from that sphere of thinking.

“There is a question that needs to be asked: why have dictatorships been so obsessive about preventing people from creating real art? Why do they need to control it? And if dictatorships are obsessive about controlling it, we have to ask, what could be the benefits of unleashing it?” He lets the question hang.

At a dinner celebrating the opening of the Centre for Openness and Dialogue, held in a freshly opened courtyard that was formerly a car park, I sit next to a local publisher, Piro Misha. I ask him what he makes of the centre. “It was like a castle from Kafka,” he replies. “It needed to be deconstructed, to show the public that nothing was off limits any more.”

Rama is in expansive mood, making jokes about the purple floodlighting and carpets: “They are in the party colours,” he says. “They were left over from the campaign.”

–Financial Times