“Don’t mind the mess,” says Alan Teller, wearing an “I love New York” T-shirt as he opens the door. Wishful slogan perhaps, considering that Teller and his wife Jerri Zbiral have spent the last few months in Kolkata, India putting together a rather unusual art exhibit and will leave for New York the next day.

Zbiral walks in, a red bandanna tied around her head. “It’s so hot!” she says, referring to the sauna-like climate that engulfs Kolkata in April. The strains of a man singing, accompanied by the clack-clack of stones drifts in through the window.

Teller fishes out his phone to take photos through the window of the modern-day wandering minstrel on the road below. “It’s that man again. He was serenading you yesterday,” he says to Zbiral as he clicks photos. “We have met such interesting people here.”

The couple from Evanston in Chicago are in Kolkata for the exhibit, “Following The Box”, based on old photos they stumbled upon 27 years back.

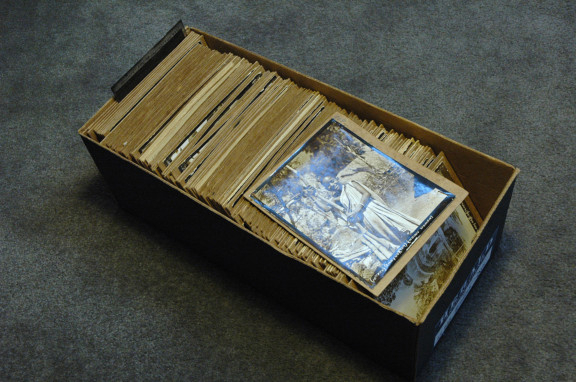

It was at an estate sale in Chicago that Teller and Zbiral chanced upon a shoebox filled with 130 brown envelopes — each containing a negative inside and with black-and-white prints stapled in the front. Perhaps it was a shared interest and background in photography that made them pick it up — for $20 (Dh73).

Back home, they pored over the photos and noticed that the captions at the bottom mentioned “10th PTU” with a date (most were taken on April 27 or May 3, 1945). The notations also mentioned India. It seemed like the photographer had been trying to record village life in India; most were of people going about their life in the rural countryside — a woman stuffing betel leaves, people washing clothes, ploughing fields, catching fish.

There are a few shots of American soldiers. Some of the subjects look posed, as though they were acting out for the camera — like the two village children with sticks of gum (probably given by the photographer) in their hands, grinning at the camera. The caption reads “Indian kids chewing gum”. A pre-teen young girl with a soft round face is labelled as an “Indian woman”. “Laundry”, says a photo of dhobis washing clothes, smashing them against rocks.

Zbiral and Teller found themselves enchanted and curious about the photos and the photographer’s identity. “We sensed a respect for the people and their life in the photos, a cultural awareness that was unusual for that time,” says Teller.

They used archival-quality materials to store the photos and put them away in a closet for the time being, as jobs, projects and the bringing up of two children took precedence. Zbiral is an art dealer and Teller is a photographer and designer of museum exhibits.

It was in 2005 that they finally got a chance to revisit the photos from India through a class Teller was taking on photography and anthropology. “I used the photos as an exhibit for my students,” says Teller. “That was the first time anyone other than us had seen the pictures.”

It was a student who figured out that the photos were from Bengal after researching on the American army presence in India during the Second World War. That was a time when a Japanese invasion in India had seemed imminent and the US Army Air Corps had stationed bases in what is now West Bengal to fly reconnaissance missions over Burma (Myanmar) towards China.

The “10th PTU” notations stood for “10th Photographic Technical Unit”, which was assigned to take aerial photographs during those missions. The size of the negatives led them to believe that the photographer had probably used a Speed Graphic, an army-issued press camera.

When the class ended, life took over again and they left it at that until their son Max, a musician, got a scholarship to study Indian classical music under santoor maestro Pandit Shiv Kumar Sharma in 2011.

Zbiral and Teller decided to visit. This would be a great opportunity to see India and revisit the box of photos which seemed to be lying in the closet, demanding answers. “We don’t really do the touristy thing, we love to get into a culture,” Teller says. “The box of photos gave us purpose and gave us an entry into India.” So they made copies of the photos, put them into a binder and carried it to India for a preliminary research trip, determined to find out the story behind the pictures.

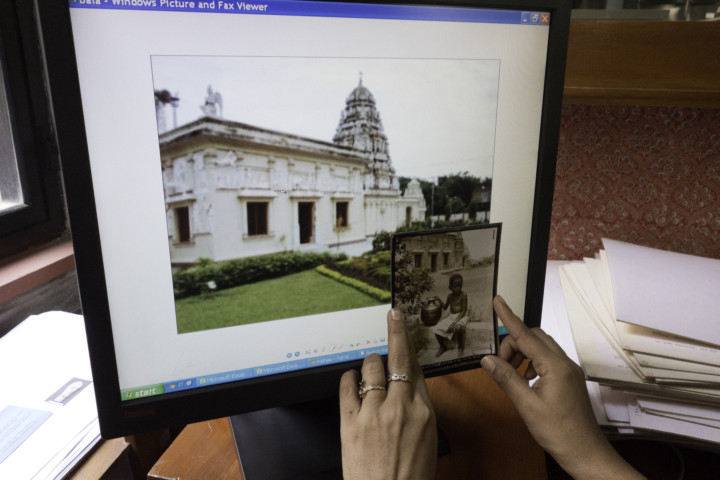

Their first stop was at the American Institute of Indian Studies (AIIS) in Gurgaon. “Among other things, they are trying to catalogue all the temples in India,” Teller says. “We thought if we could identify even one of the temples in the photos, we could identify where the photos were taken.”

With AIIS’s help, they were able to identify a place where their photographer had been — the Karanagarh Temple near Piardoba airfield near Bishnupur in Bengal, a site of a former US army air base and now an abandoned airfield. They set off for Bishnupur with the photos, intending to show them to people to trace other places, and eventually the photographer.

“We became instant rock stars,” Teller recalls. Whenever they opened the binder, people would surround them, wanting to see this slice of old history of their area.

While Zbiral and Teller were tracing the photos, they found a bond growing between them and the mysterious photographer. Teller recalls taking photos of a man playing the harmonium in front of a temple. The picture was uncannily similar to one taken by the American soldier so many years ago. He submitted an artwork which was a combination of his photo and the older one to a photographers’ magazine. “I realised that the American soldier’s work can inspire the creation of new work,” Teller says. “The pictures are not dead, they are living.”

A germ of an idea grew from there — use the old photos to create new art. If the photos had garnered such reactions from ordinary people, maybe they could inspire other people too. “Here’s an American artist with his perception of India, maybe we can get Indian artists who can translate their perception of this guy looking at their culture,” Zbiral says.

That became the basis for an application for a Fulbright grant for a project that would be a cross-cultural look at the photographs with artists in India reflecting back on work done by an American photographer 70 years ago.

The couple returned in 2013 with a Fulbright-Nehru grant for a project which would, one, enable them to gather further information about the photos and, two, get Indian artists to create work based on their responses to the box. They spent five months in Kolkata working on identifying artists for the project and to gather more information and track down the photographer.

In the latter, they were helped in part by the students of Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur. They had noticed a notation on some of the photos — “Salur”.

College students who joined the project as translators and research assistants suggested that the R at the end of “Salur” was actually an A, as there was a Salua Air Force base nearby. Built in 1942, Salua was a Second World War air base and had housed a Heavy Bomber Squadron. It was used by the 317th Airlift Squadron of the US Air Force and was the first base of operations for the B29 Superfortresses (units of the 58th Bomb Wing).

Today it is a radar station. With the help of the students and some connections, they were able to get on to the base. When approached, the Gurkhas at the base were more than willing to help — they helped the couple identify a laundry, a wall and a pond seen in some of the pictures.

“They fell in love with the photos, took them to surrounding villages showing them to people,” Zbiral says. The Gurkhas and Zbiral-Teller are now Facebook friends.

The discovery of Salua was the turning point in their quest. The students informed them that their campus had been a former air base. A darkroom was discovered which had been operated by the 10th PTU, which led them to realise that the notations may have referred to the processing lab, not to the photographer’s unit. Now they knew that their photographer was associated with a Combat Camera Crew, flying out of Salua.

An internet search for old soldiers stationed at Salua threw up a blog entry about a Lewis Paltz who had been a reconnaissance photographer stationed there. Later, it turned out to be a red herring as Paltz was sent to China after Salua and their mystery photographer had gone to Okinawa.

The photographer’s identity continues to be elusive, which in a way is good, as it means that the search continues. Teller and Zbiral are aware that the mystery of the photographer’s identity is one of the greatest attractions of the project.

Meanwhile, their journey to track down the photographer has touched many lives in India and the US. Like the Gurkhas, everyone who came in touch with the photos felt a connection. “It’s like a magnet that draws people,” Zbiral says. “This is just what we wanted, we are just conduits.”

They talk about an incident at the Balaji temple in Kharagpur — one of the many featured in the photographs. They were showing photos at the temple site, the usual crowd had gathered around them, when a photo labelled “Old Priest” of a man in a dhoti standing in front of the temple grabbed the attention of someone.

“‘That’s my great-grandfather!’ yelled this man from the crowd,” Zbiral recounts. Next day the man brought the 90-year-old daughter-in-law of the “Old Priest”, who it turned out was a certain Narayanswamy Naidu, the founder of the temple.

With the Fulbright grant, the couple were able to execute the second part of the project — getting artists from India to interpret the photos their way. “It became a community project,” Zbiral says. “We had dinner at each other’s houses.”

The artists created a wide variety of works across different fields — painting, art-installations, collage, story scrolls, photography and a graphic novel. One artist created a short film that used the photos with a narration by the imagined soldier who (the artist decided) was a Jew from Baltimore who had worked in his uncle’s photography studio before he got drafted.

A photographer documented the life of a cricket umpire who was born on April 27, 1945, the same day some of the photos were developed. Jerri created a jigsaw puzzle with the photographs because “it is a mystery we are yet to unravel fully”.

“Following the Box: An Artistic Exploration Of An Archive Of Anonymous Photographs From India” had its first showing at the Birla Academy of Art and Culture in Kolkata in the second week of February 2015.

It had over 2000 visitors. “One visitor said thank you for bringing the photos back, they are a part of my childhood,” said Zbiral. After wrapping up in Kolkata, “Following The Box” will travel to Delhi and Mumbai.

A film on the project premiered at the New York Indian Film Festival on May 7th.

Zbiral and Teller have also put together an exhibit of eight panels based on photos, stories and information about their project. The panels also place the photos in context with India in 1945, when the country was two years from independence: Bengal had been devastated by a famine which was exacerbated by Britain diverting rice.

This was when Subhas Chandra Bose, the Bengali leader of the Indian National Congress, had declared, “Freedom is not given, it is taken.” There were rumours that the Japanese were planning an invasion of Kolkata.

“The most interesting part is that initially we knew nothing about the photographs. Things manifested, as life does, on our way forward,” says Teller. The exhibit will be shown at American consulates in Delhi, Chennai, Hyderabad, Kolkata and Mumbai.

Zbiral and Teller are now back in the US. “We came via Dubai and managed to see a bit of it in the ride from the airport to the hotel,” Teller says. “Very strange to think that at least some of the people we saw were likely to be reading about our project in the near future; as if we knew the future!”

Teller will be back in India in a couple of months to prepare for the Delhi opening of “Following The Box”. The Fulbright is over, and they are getting freaked out about the time line. “We haven’t had time to do serious fundraising. To develop a major show, most museums get corporate backing,” Zbiral says.

They’ve had meetings with potential funders and remain hopeful.

The identity of the photographer may remain elusive, but — as the exhibition concludes “... as new clues surface, it becomes ever more apparent that history is alive, that all of us play a part. Untold stories lie hidden in countless shoeboxes. We just have to make the time to look”.

Anuradha Sengupta is a writer based in Mumbai.