It is one of the most prominent symbols of Pakistan’s Buddhist heritage — a giant 7th-century rock sculpture of Buddha sitting in a meditative pose in Jahanabad, Swat. It’s an image of peaceful contemplation far removed from the hustle and bustle of modern urban life.

That peace was shattered on September 2007 when the Taliban blew up half of the sculpture’s face by drilling holes and putting explosives in it. It takes only a few minutes (and little skill) to carry out such an act of wanton destruction. But to fix it requires years of patience and devotion. In 2012, the Italian Archaeological Mission in Swat started the restoration of Buddha’s face. The process lasted a few years and was eventually completed in October 2016.

The reconstruction of the Jahanabad Buddha is just one of many accomplishments of the mission, whose work in Swat spans more than six decades.

“If you consider that the Italian mission has been present... working here practically without interruption for more than 60 years, you can imagine what is the magnitude of the fieldwork that we did. And how many people were involved in total,” Olivieri says.

The first time he came to Swat was in 1987 when he was 25 years old and still a university student.

Olivieri — who always wanted to be an archaeologist — graduated from Rome University and did his PhD in Berlin. Before coming to Swat, he participated in many excavations in Rome on the Colosseum and Palatine Hill. “As soon as I put my feet on the soil of Swat, I remember that I crossed my fingers, hoping that they would call me back again because I immediately fell in love with Swat,” he says.

Swat used to be an autonomous political entity until 1969 when it merged into Pakistan. When Olivieri arrived in 1987, there were still traces from this past era.

“Swat was everything,” he tells Weekend Review. “People, landscape... You know when I say I fell in love with Swat, is there a reason for a man to be in love with a woman? It is something very intimate. Something you feel. It is difficult to explain.”

In fact, even before travelling to Swat, he felt a connection with Pakistan. “I was amongst the very few Italians playing field hockey. I remember when I was very young, 14 or 15 years old, I was playing hockey in Italy. It was impossible without having in the mind the great Pakistani field hockey team. One of the trainers in my team was a Pakistani guy. So all the hockey sticks we had were produced in Pakistan, from Sialkot.”

In Swat, his mentor was Domenico Faccenna, considered to be one of the founders of Buddhist archaeology in Pakistan. Faccenna had worked in Pakistan since the 1950s after being initiated by a famous orientalist, Giuseppe Tucci. The story of the Italian Archaeological Mission in Pakistan starts with him.

“[Tucci] was busy during the 1930s and early 40s exploring Tibet,” says Olivieri. “He was one of the most important explorers of that part of Asia. During the 1950s, after the Second World War, he became interested in how Buddhism arrived in Tibet. The Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism introduced in Tibet around the 7th and 8th centuries originally spread from Swat.”

Swat was at the time known as Uddiyana in the Buddhist world, especially in Trans-Himalayas. It was considered by Buddhist schools in Tibet and China as the motherland of Buddhism.

“There was a flow of pilgrims coming back to Uddiyana and visiting this sort of sacred land. Since the early times of Buddhism, even before Buddhism was introduced into Tibet, the first monks who visited Swat were Chinese. Faxian and Xuanzang are the most famous,” Olivieri says.

“Tucci, during the exploration of one Tibetan library in a Buddhist monastery, found the travel log of three Tibetan pilgrims. He published these travel logs in 1940 in Calcutta [now Kolkata]. And then immediately after the Second World War he made a very important survey of the Swat valley,” he says.

In 1955, Tucci established the Italian Archaeological Mission in Swat to explore the origins of Buddhism.

From the beginning the Italian mission was busy with archaeological excavations at Buddhist sites. The most famous one was in Butkara, an ancient monastery very well known in Tibetan and Chinese circles as Tolo. But there were other sites to explore.

“Immediately after the excavations of Butkara, other teams started working in the cities which were believed to be the ones pillaged and conquered by Alexander the Great in 327 BC,” Olivieri says.

In 1984, a new excavation project was started at Barikot in Swat — known as Bazira in Greek — and identified in later sources as one of the cities conquered and refortified by Alexander. When Olivieri went to Pakistan in 1987, he worked on the excavation there.

The earliest evidence found at Bazira goes back to the late Bronze age and early Iron Age. Olivieri describes the city as having a typical Hellenistic military architecture.

“It had a very long acculturation phase sharing multicultural material with Greek and Bactrian sites in Central Asia like Ai-Khanoum and Afrasiyab. Then we found the construction of a defensive wall, which was made by the Indo-Greeks in 15 BC. The Indo-Greeks are dynastic kings of Greek descent that established a very large kingdom in northern India. Their capital was in Pataliputra, which is nowadays Patna in the Ganges plain,” he says.

After the Indo-Greeks, the city was occupied by the Sakas, the Parthians and finally the Kushans. After two massive and destructive earthquakes during the 3rd century AD when the Kushan empire collapsed, the area was put under the rule of the Sasanians.

“The city was abandoned,” he says. “This is a very important piece of information because it is a common trend in the northern regions of south Asia, the crises of urbanism around the 3rd century.”

The number of monasteries in the settled area built by Buddhist monks in Swat was incredibly high.

“When the city of Barikot was abandoned and became just a field of ruins, all monasteries in the settled areas in the surrounding countryside remained alive, and they were still working in the 7th and 8th century. So, we can say five or six centuries after the abandonment of the city of Bazira, Buddhism in settled areas and monasteries was still flourishing.”

Olivieri describes Swat as one of the safest places he visited from his first arrival in 1987 to 2004.

“It was extremely safe. Neither me nor my colleagues had any kind of problem in Swat… the attitude and the tradition of hospitality that we experienced was extremely warm. It was an extremely safe place to stay and to work. Everything changed, of course, during the Taliban period. But in my view, the roots of that has nothing to do with the basic Swat tradition. It is something that was imported to Swat.”

After the Taliban showed up the security situation deteriorated. There were reports of floggings, executions and the destruction of property. Among the places affected was the Swat Museum. Established by the Italian mission in 1958, the building was later expanded by the Pakistani government. In 2005, it suffered extensive damage due to the Kashmir earthquake. Then in 2008, there was a huge bomb blast just in front of the museum in which 70 people died. Although the museum was not directly targeted, it was badly damaged.

The museum stood empty after the bombing.

“The Federal Department of Archaeology at the very beginning of the Taliban offensive in Swat moved all the museum’s objects to Taxila. So when the bomb blast occurred in 2008, luckily the museum was empty,” Olivieri says.

How many sculptures were damaged by the Taliban?

“Honestly speaking, not much. These people were not much interested in Swat’s archaeological heritage. Of course, the Jahanabad Buddha was impressively visible, and for that reason it attracted these people,” he says.

From 2008 to 2010 the Italian Archaeological Mission couldn’t go to Swat because of the security situation. But they did keep up regular contact with landlords and local caretakers.

“The Italian mission is a permanent institution in Swat,” says Olivieri. “We have a place, the same place which was established by Tucci. We have a library and guest house.”

The mission also has some sites under their responsibility.

Immediately after the end of the military operation in 2011, the Italian mission applied for a large-scale programme, funded under the framework of the Pakistan-Italian Debt Swap Agreement. This project included many activities for the protection of Swat’s cultural heritage. One of the most important one was the reconstruction of the Swat Museum.

Exactly 50 years after the inauguration of the Swat Museum in 1963, it was reopened on November 11, 2003. It has been rebuilt as a modern building constructed according to a seismic-resistant design.

“It was an incredibly great achievement because we made the entire work of demolishing, reconstructing the museum and reorganising the display in less than two years. The museum is now one of the best pieces of architecture you have in Saidu Sharif in Swat,” he says.

Following the military operation in Swat, the Italians also resumed work at Barikot and have made important discoveries there in the last two years. They include traces of the city that was besieged by Alexander the Great’s army in 327 BC.

Today archaeological tourism in Swat is on the rise. Most of the tourists are locals but there are also some foreigners.

“There is a new trend that is represented by Buddhist tourists who visit Pakistani archaeological sites purposely to see the Buddhist ruins and heritage. They come from South Korea, China, Thailand and Bhutan.”

One of the positive side effects of the Italian mission’s large-scale work has been the popularisation of archaeology in Swat.

“We have television programmes, documentaries and features broadcast in Pashtu and Urdu on regional and local television and on the internet,” he says.

“When you work in a Pashtu speaking environment you should know something in order to be understood,” he says. “My Pashtu is okay for archaeological excavation. My colleagues and I are able to interact with our workers.”

Olivieri is the author of a number of books on the archeology of Swat. He has also written the first archaeological manual purposely designed for Pakistani students. Previously, archaeology students had only old books written by British archeologists like Mortimer Wheeler and Sir John Marshall. The manual includes updated methodologies seen through a practical point of view.

“Practically in the book you can see how to start an archaeological work from the beginning. How many workers you need. How the workers should be organised What kind of equipment you need. How to organise the disposal of waste soil. How you can proceed in documentation and digging,” he says.

Olivieri has extremely well-trained local workers in Swat. “Our staff in Barikot includes at least 30 to 35 local workers whose ability in digging can be compared to good PhD university students in Europe. So, they actually know how to make an excavation.”

Among the Italian mission’s many accomplishments is the excavation near a place called Udegram, where they discovered the third-oldest mosque in Pakistan. It was established by Mahmud of Ghazni in the 11th century, and the team worked on the site between 1984 and 1999.

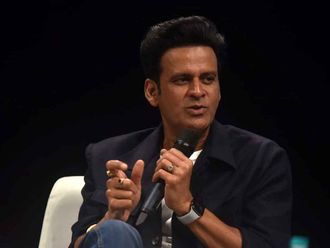

Nearly 95 per cent of Olivieri’s professional life has been spent in Swat. Over the past half decade, Olivieri has spent up to six months a year in Swat. Last year, in recognition of his services to protect the archaeological heritage of Pakistan, he was awarded the Sitara-i-Imtiaz, the third-highest civilian award in the country. “The Italian Mission has three Sitara Imtiaz,” he says proudly. “First was Gherardo Gnoli, the president of ISMEO — The Italian Institute for the Middle East and Far East after Tucci — and then Domenico Faccenna, and I was the third recipient.”

Syed Hamad Ali is a writer based in London.