Ask people what Margaret Thatcher’s view of apartheid was and they would probably guess she was in favour, and regarded Nelson Mandela as a fanatic best kept in jail. Such is the power of stereotype. Yet Thatcher opposed apartheid and she lobbied Pretoria incessantly for Mandela’s release.

She parted company with the liberal consensus only on the efficacy of sanctions as a lever on the South African government. On that she was probably right.

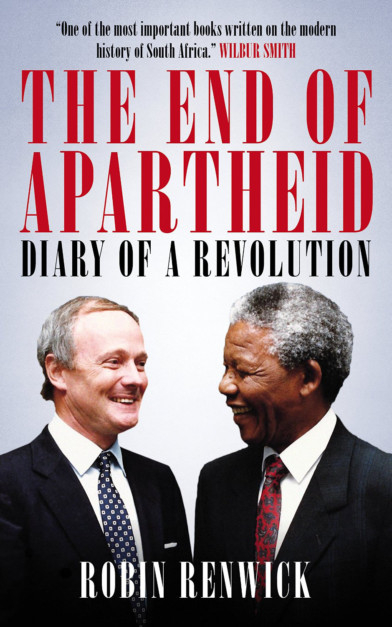

Few diplomats nowadays get an opportunity to play a significant role in the affairs of their host country. So when Robin Renwick was appointed ambassador to South Africa in 1987, he can hardly have expected a thrilling time. He had helped negotiate the end of white minority rule in Rhodesia in 1979, but its South African neighbour was then securely in the grip of P.W. Botha’s white nationalists.

The regime had an efficient army and a repressive police force. Insurgency was minimal, despite hostile frontline states across the borders in Angola, Zimbabwe and Mozambique. Trade sanctions had reinforced Pretoria in its self-righteous isolation, incidentally ridding the country of foreign profit-takers.

South Africa’s economy was Africa’s strongest. The sports boycott was irritating, but not remotely such as to induce Afrikaners to capitulate to a black majority.

Covering South Africa for the Economist in the 1980s, I could see no reason why this should change any time soon. The whites were entrenched. The most effective opposition came not from the banned African National Congress but from a minority of liberals led by the English language press and the solitary anti-apartheid MP, Helen Suzman .

That they were allowed considerable licence to attack the regime was a sign of its strength — though it is possible that in time they did begin to tax the conscience of some of its members. Then suddenly in 1989-1991 came a revolution.

The period covered by this book is so embedded in the history of popular struggle that reality is often hopelessly mixed with make-believe. This is largely due to the eagerness of so many players outside South Africa to claim credit for the downfall of apartheid and Mandela’s subsequent apotheosis. In reality, the ending of apartheid was the outcome of a specific crisis within Afrikanerdom, in which outsiders played little or no part.

The immediate catalyst was banal. In 1989 the bigoted and intransigent Botha had a mild stroke. He was unable to assert authority over his cabinet colleagues, and National Party moderates, “or verligtes”, moved into the ascendant, cohering round the Transvaal leader, F.W. de Klerk, as Botha’s natural successor.

De Klerk had no previous record as a liberal. What happened next was equally crucial. De Klerk had a Damascene conversion, boldly and emphatically turning to reform. He realised that apartheid was losing intellectual and moral sway over the white minority. He could see the game was up. So-called “separate development” was administrative chaos, with black immigrants pouring into the lucrative mining sector and spreading south into the Cape Province. Most whites sensed change had to come, but they were terrified of what it might mean.

Within months of Botha’s illness, de Klerk won election as leader and negotiations began with Mandela, now released from prison into comfortable house arrest. Within three years de Klerk’s nationalists won an election, bitterly fought by an emergent rightwing.

A whites-only referendum on ending apartheid was passed and a new constitution was introduced. In 1994 Mandela became president in the most moving election I have ever witnessed, the only time in modern history that an authoritarian oligarchy peacefully ceded power to a majority.

Renwick is clearly frustrated at the neglect of Britain’s role in all this. He duly secured Foreign Office permission to reveal Whitehall documents covering the period, a useful precedent for future possible breaches of the 30-year rule. He shows himself as a hyperactive diplomat, never out of the limelight. He has contacts everywhere, in the cabinet, the press, the Afrikaner establishment, the radical opposition, even the banned ANC.

With apartheid crumbling and power shifting uneasily from group to group, Renwick, like Pinocchio’s conscience, admonishes all and sundry to be good. How significant this was to the course of events is unclear. Certainly, Renwick appears to have been operating at the limits of diplomatic courtesy. The diary entries become frenetic. Whomever he addresses, “I advised him to release detainees ... I warned him against the advice of the head of the security police ... I raised the issue of the abolition of the death penalty”.

When the die for reform is cast, Renwick is in full proconsular mode. “I asked the ANC to consider suspending the sports boycott ... I asked for the state of emergency to be restricted to Natal ... I congratulated Mandela on the suspension of the armed struggle”.

To the question, did Thatcher will all this, the answer is plainly yes. She was kept well informed and supported Renwick, even when there was no certainty of outcome. She wrote to Botha in 1988 calling for Mandela’s release, warning of what might happen if he died there. At Renwick’s instigation she subsequently engaged with de Klerk, actually inviting him to Chequers. He later said she “was far tougher with me than any other European leader”.

She also received the wife of the veteran activist, Walter Sisulu, gave an interview to the black newspaper, the Sowetan, and pleaded in every communication for Mandela’s release.

Even ambassadors are mortal and Renwick in 1991 was rewarded with promotion to the embassy in Washington. The South Africans, he implies, would now have to fend for themselves. “I left with an unaccustomed sense of humility,” he writes, though he does insist that the transition was achieved by South Africans themselves, “not by any outsider, however well intentioned”.

Renwick was clearly in a position rare for an ambassador. The politics of boycott had stripped even a Republican US president, George Bush Snr, of leverage over Pretoria. Britain had kept in touch. It shared a language and an imperial history with South Africa. Insofar as any outside country mattered to at least moderate South Africans, Britain did. Renwick exploited even the smallest leverage this offered.

Both de Klerk and Mandela were afterwards explicit in thanking Thatcher for what they perceived as her support. Mandela thanked her for pressing for his release. On hearing of her fall in 1990 he said: “We have much to be thankful to her for.” Of her handling of de Klerk, she had intuited how best to assist a country facing a great upheaval and uncertainty. She was doing much the same, albeit more directly, with Gorbachev at the time.

Thatcher opposed sanctions not from any favouritism towards white South Africa but because she thought them ineffective. She saw them as hurting black workers while disinvestment enriched Afrikaner monopolists. They enabled the South African economy to sustain apartheid longer than would otherwise be the case. That the anti-apartheid movement thought otherwise — and vilified Thatcher as a result — complicated but did not demolish her belief.

Ironically, Renwick had written a powerful study of sanctions against the white Rhodesian regime, which came to much the same conclusion. They merely led to a far higher degree of self-sufficiency while penalising Rhodesia’s neighbouring trade partners. The brave, for many years solitary, campaigner against apartheid, Suzman, agreed, as did Desmond Tutu until he visited America and was persuaded otherwise by anti-apartheid activists.

It probably cost Suzman the Nobel prize that was certainly her due. I would have liked more from Renwick on sanctions, if only because those on South Africa are so often cited as a rare success, because eventually South Africa did change. Clearly, at the end, the possible dismantling of sanctions was a reward on the horizon. Sporting fixtures after the referendum were a bonus to white opinion, though it is still hard to believe they influenced many votes on what was a matter of great constitutional import. The eternal arrogance of western policy makers is to think the world hangs on their every measure. Sanctions may “hurt”, but that does not make them “effective”. In this they are like dropping bombs. Reality is usually eccentric. Had Botha not had a stroke or had Mandela died in prison, more rabid elements (notably in South Africa’s security apparat) might have seized control of events. As it was, fortune blessed South Africa with two leaders — Mandela and de Klerk — of courtesy, clarity of thought and generosity of spirit.

Renwick was privileged with a front seat in this drama and did all that his profession allowed to urge it forward. As for Thatcher, he has at very least put the record straight.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd