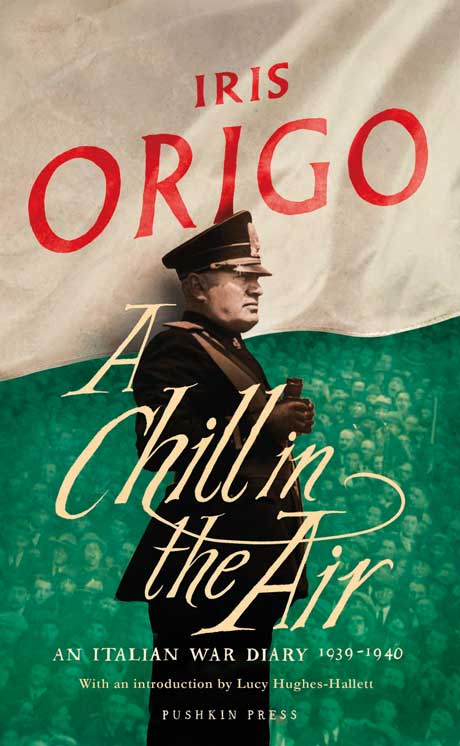

By Iris Origo, Pushkin, 200 pages, £14.99

The best diaries of the Second World War were written by women, and this is no paradox. Their observation and analysis of events around them deepened with the idea that they were living through a crucial moment in history that they felt a duty to record. These remarkable writers — who included Lydia Ginzburg, Ursula von Kardorff and the anonymous author of A Woman in Berlin — pondered the unpredictability of human behaviour, as war often brought out the best in people as well as the worst.

As Lucy Hughes-Hallett points out in her excellent introduction to this volume, Iris Origo, with typical modesty, referred in her memoirs to her “little war diary” in no more than a passing subordinate clause. In fact War in the Val d’Orcia, first published in 1947, was immediately hailed as one of the great diaries of the 20th century. It described the chaos and suffering of Italian civilians caught between the Allies and the Germans in 1943 and 1944.

The Anglo-American Marchesa Origo, owner of 7,000 acres and 25 farms southeast of Siena, sheltered and fed anti-fascist partisans and escaped British prisoners-of-war, as well as refugees from allied bombing.

Caroline Moorehead, in her biography of Origo , records that while she helped hide these fugitives at great risk, her husband Antonio, who had forsworn his earlier support for Mussolini, would be “tying up a German patrol in conversation at the front of the house”. Then, when the fighting drew near and the Germans forced them to abandon everything, the couple shepherded a crowd of about 60 women with babies, children and the elderly through artillery fire to safety atMontepulciano.

This volume, a worthy counterpart to War in the Val d’Orcia, focuses on Mussolini’s fatal miscalculation that, heedless of the dangers for Italy, he could side with Hitler to extract maximum profit from a German victory. Origo decided in March 1939 to keep the diary to help her remain “steady” as the government of her adopted homeland became increasingly hostile to her two countries of origin.

The “chill in the air” of the title refers both to Mussolini’s dictum that “perpetual peace would be a catastrophe for human civilisation”, and the danger of an alliance with Nazi Germany. The Tuscan contadini, whose parents’ lives had been squandered in 1917 on the allied side during the terrible fighting in the Dolomites, had no enthusiasm for the new “axis” with the Nazis. Even as war fever mounted after the German occupation of Prague and threats to Poland, there was an air of disbelief that it could be in anyone’s interests to become embroiled in a war of Hitler’s making. “One young woman, who is just expecting her first baby, prays daily that it will be a girl. ‘What’s the use of having boys if they’ll take them away from me and kill them?’”

Italy then invaded Albania. The fascist press claimed that its army was saving the country from brigands. One and a half million men were called up, a disaster in a primarily agricultural country: even then it was far short of the “eight million” bayonets of Mussolini’s ludicrous boast, which prompted jests about the lack of rifles to put them on.

Origo analyses the propaganda lies with the piercing intelligence that so impressed Frances Partridge and Virginia Woolf. “It is now clear what form propaganda, in case of war, will take,” she writes. Mussolini will accuse the “haves” of the “democratic countries” of blocking the economic expansion of the “have-nots” by not sharing colonies and resources. And Germany’s behaviour would be justified on the grounds that by offering a guarantee to Poland, the British and the French were guilty of attempting to “encircle” Germany. The fake news issued by the regime was so implausible that many were tempted to dismiss all news, however accurate, as no better. “The radio has made fools of us all,” a man says to her.

Origo manages to sum up the corruption in all dictatorships with a simple anecdote. “A little boy of 10, the son of one of my friends, was highly praised for his school essay, which was full of the most orthodox fascist sentiments. When he brought home a rough copy, his mother asked him: ‘Do you really believe all this, Luigino?’ ‘Oh no, mother, of course not! But it is the only way to get good marks’.”

War fever abated in the late spring of 1939, when Mussolini claimed that only Britain and France wanted to fight. The dictatorships simply desired “peace and justice”. Despite the wild rumours and the endless propaganda, Origo clearly saw the direction of events. A month and a half before the Nazi-Soviet Pact exploded like a bombshell in the capitals of Europe, Origo spotted it coming. She was, of course, helped by being extremely well-connected and in touch with fascists, antifascists and foreigners, such as her godfather — the American ambassador in Rome. A close associate of Mussolini described to her the Duce’s contempt for humanity: “A sentimentalist about ‘the people’ en masse, he is completely cynical about all individuals, and measures them only by the use he can put them to.”

Unfortunately all too many Italians believed Mussolini would avoid an entanglement with Hitler. “Don’t you worry, nothing’s going to happen,” Origo’s hairdresser says when he spots her reading the newspaper. “You’ll see, the Duce will stop the war at the last moment,” a taxi driver tells her. In the countryside, the contadini are under no illusion. “One old man, whose four sons work on the farm, put a shaking hand on my arm and looked up into my face. ‘If they all four go, I might as well throw myself into that ditch. Who will work the farm? What shall we give the children to eat?’”

On September 1, Hitler invaded Poland, claiming that the fault lay with the Poles for having mobilised when German armies massed on her borders. “Total silence from Rome,” Origo notes. But those who admired Mussolini for keeping Italy out of the war would be disabused. In June 1940 he became the jackal to Hitler’s lion, declaring war on Britain and France just as the victorious Germans were poised to enter Paris. All Italians were summoned to the wireless to listen to his bombastic speech. The contadini can do little but shrug and turn away. Their “rough, awkward country boys dressed up in ill-fitting uniforms” will pay the price.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd

Antony Beevor’s Ardennes 1944 is published by Penguin.