This Orient Isle: Elizabethan England and the Islamic World

By Jerry Brotton, Allen Lane, 384 pages, £20

Elizabeth I’s England stood isolated and vulnerable, fighting for its very survival amid an onslaught from Catholic Spain. So, with traditional allies fading away, the Queen made a brave, calculated decision to look east and engage the Muslim world in an attempt to boost trade and expand her power base.

English merchants and diplomats subsequently spent much of the second half of the 16th century making extraordinary journeys across dangerous lands and being granted audiences with powerful yet unpredictable rulers as they sought to help bring prosperity to their relatively obscure homeland.

It is the stories of these adventurous individuals that bring Jerry Brotton’s “This Orient Isle: Elizabethan England and the Islamic World” to life. Although “This Orient Isle” is ostensibly about how a politically isolated English queen reached out in search of new allies after falling foul of the established Catholic powers of western Europe, it is the tales of people such as Thomas Dallam, Anthony Jenkinson, William Harborne and Sir Anthony Sherley — as well as the first Muslims who turned heads in London and influenced a generation of playwrights, including William Shakespeare — that make the book memorable.

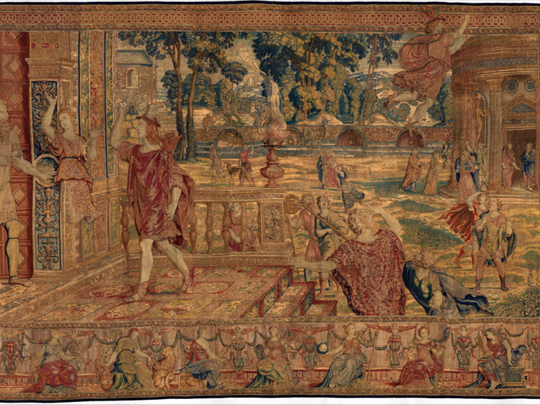

For example, Dallam, then a 24-year-old from Warrington in Lancashire, was returning home from the journey of a lifetime in December 1599, having assembled and played an elaborate clockwork organ that was gifted by Elizabeth to the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed III — then the most powerful ruler in the world — when he was involved in a bizarre coincidence.

After four months in the royal court in Constantinople, where he impressed the sultan so much he was offered the pick of the ruler’s harem, Dallam travelled as far as the Greek island of Zante with a guide named Finch, who hailed from Chorley, some 30 kilometres from his home town in England. They may have had much in common thanks to their shared roots but, once the pair parted ways, Dallam returned to life as a noted organ builder in Elizabethan England, while Finch — who had converted to Islam, or “turned Turk” in the lexicon of the day — went back to the incomparable world of 16th century Constantinople and his position as a dragoman.

Jenkinson, meanwhile, was regarded as one of the great pioneers of Elizabethan travel, Brotton says. The textile merchant-turned-diplomat negotiated unprecedented trading rights with Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent in Aleppo in 1553, before being chosen to lead successive expeditions with the aim of opening up a trade route through Russia to Persia, during which he charmed tsar Ivan the Terrible in Moscow only to be thrown out of Shah Tahmasp’s court in Qazvin and was fortunate to escape with his life.

Brotton describes how Jenkinson’s “success paved the way for further and even closer alliances between Elizabethans and Muslims over the next four decades”. But his chastening experience in Persia put into context the struggles facing Elizabeth’s ambassadors as they tried to negotiate beneficial deals so far from home, as “nobody at the shah’s court knew anything about this tiny place called England, its female ruler or its “famous city” of London”.

The title of the book plays on the famous “this sceptred isle” speech from Shakespeare’s “Richard II”, which also describes England as a “precious stone set in the silver sea”, but in reality the country at this time was debt-ridden, beset by political and religious strife and constantly battling the threat of Spanish invasion.

As dealings with the Muslim world increased during Elizabeth’s reign, so outrage and fear in English society grew. And the playwrights of the day began reflecting those concerns, with an early example being Robert Wilson’s “The Three Ladies of London” (1581), which criticised greed and consumerism, describing the trade in trinkets as “fit things to suck away from such green-headed [covetous] wantons”.

Brotton also recounts how Catholic exile Richard Verstegen stoked anti-Muslim sentiment by condemning English alliances with “infidels, heretics and rebels”. Then a letter from the Ottoman Safiye Sultan to Elizabeth — with whom she had been exchanging lavish gifts — confirmed how Constantinople thought of England. “As far as Safiye was concerned, regardless of the presents exchanged between them, Elizabeth came under [Sultan] Murad’s imperial and theological protection. Her letter unwittingly confirmed the accusations levelled against Elizabeth and her Protestant counsellors by Verstegen and the exiled English Catholic diaspora: England was being treated as a vassal state of the Islamic Ottoman Empire, prepared to trade anything from cloth and pictures to its faith.”

Brotton’s background is as a literary scholar and his knowledge of and passion for Elizabethan playwrights ensures “This Orient Isle” has more depth than it would had its sources been limited to official accounts, letters and memoirs. He describes with authority the changes in how the Muslim world is represented on stage in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, from Christopher Marlowe’s barbaric, bombastic Tamburlaine to Shakespeare’s more subtle, ambivalent Moor Othello.

He also hints that the great bard’s inspiration for the character Othello could well have been Moroccan ambassador Abd Al Wahid Bin Masoud Bin Mohammad Al Annuri, who led a mission to England in 1600 and twice met Elizabeth to negotiate a potential Anglo-Moroccan alliance that would involve a joint attack on Spain. Their discussions ultimately came to nothing, but Al Annuri — who left the country just a few months before Shakespeare began writing “The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice” — would have been a remarkable figure whenever he was in public, particularly at the Queen’s extravagant Accession Day Tilts in November 1600.

He even sat for a portrait during this time and Brotton muses: “Looking again at Al Annuri’s portrait, and retracing his movements across London in 1600-01, it is possible to discern some of the local raw material on which Shakespeare may have drawn for his portrayal of the ‘noble Moor’. Like Al Annuri, Othello is simultaneously admired and feared by his Christian hosts. He is cultivated as a military asset, yet, like Al Annuri, is denigrated as an outsider. These two men, one real, the other fictional, move into a Christian world that first embraces but eventually rejects and expels them.”

Brotton’s consistently engaging storytelling style marks “This Orient Isle” out as a fascinating and entertaining account of a previously little-explored perspective on England’s Tudor history.

In less than half a century of Elizabeth’s rule, he says, Protestant England came closer to Islam than at any other time in its history until today. And the tales of engagement with the Muslim world are particularly pertinent when juxtaposed with the country’s current struggles with anti-Islamic sentiment and the assimilation of Muslim communities. So, as the author points out, “one way of encouraging tolerance and inclusiveness at a time when both are in short supply is to show both Muslim and Christian communities how, over four centuries ago, absolute theological belief often yielded to strategic considerations, political pressures and the pursuit of wealth”.

The links between the two religious may have been defined more by expediency than tolerance, but these 16th century pioneers were able to find plenty of common ground on which to build a series of successful relationships.

Martin Downer is a freelance writer based in the UK.