History may be written by winners, but the juiciest tales are always told by losers. Nothing yields richer pickings for political commentators than a movement furiously tearing itself apart in defeat, and on that score at least, 2017 has delivered in spades. The doyen of such high-class gossip is the Sunday Times political editor Tim Shipman, whose All Out War was last year’s bestselling guide to the referendum campaign. Its sequel Fall Out (William Collins) takes up where that left off, describing first how Theresa May somehow managed to turn an almost invincible polling lead into a disastrous electoral collapse, and second the phenomenon of Jeremy Corbyn’s rise to almost-power.

Readers should be warned that it’s very much in that order; although the chapters set inside Labour’s divided HQ are meticulously done, they lack the tangible intimacy and insight of the chapters on Tory meltdown. It’s testament to the rigour of Shipman’s research that the book doesn’t feel dated despite the speed at which events at Westminster have moved since it went to press, with a string of ministerial careers now threatened by claims of sexual harassment.

Talking of which, one of the most unexpected catalysts of social change and reflection this year has been the outpouring of female anger prompted by the Harvey Weinstein scandal, with women worldwide volunteering long-buried stories of sexual abuse. At its peak #metoo began to function almost as a political movement, albeit with a small “p”. So it’s perhaps appropriate that this year should have seen so much female anger making its way into print.

The first in a spate of unmissable political books by women was Harriet Harman’s autobiography A Woman’s Work (Allen Lane), which looks newly contemporary in the wake of Weinstein. It opens with a confession about all the times she was sexually harassed as a young woman — stories it has, in some cases, taken her half a century to talk about — and closes with a poignant account of why she never dared run for the party leadership. In Everywoman (Hutchinson), her Labour colleague Jess Phillips takes aim at everything from sexual exploitation and domestic violence to body shaming in a narrative that is by turns witty and furious.

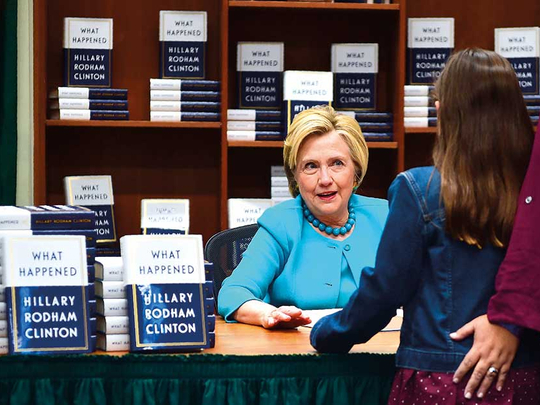

The heavyweight contender, however, is Hillary Clinton’s What Happened (Simon & Schuster). Anyone bored witless by Clinton’s stilted official autobiography a few years ago need not worry; this account of how she lost the presidential election is as close to unbuttoned as she gets. The book’s central warning about the scope and ambition of Russian attempts to subvert western politics looks ever more prescient as the months go on — including in Britain, with debate now raging over the impact of Russian bots’ cheerleading for Brexit on social media.

Ah, Brexit. The leave voter in your life, or remainers worried they might be living in a liberal bubble, might well appreciate the updated paperback version of David Goodhart’s Road to Somewhere (Hurst), his account of what drove angry provincial voters (Somewheres) to take revenge on a condescending cosmopolitan elite (Anywheres) at the referendum. If you can get past the intellectual contortions Goodhart performs to argue that what sounds uncannily like racism isn’t racism really, it’s a thought-provoking introduction to the deep regional divides exposed by the vote to leave the EU.

Read it alongside Richard Reeves’s Dream Hoarders (Brookings Institution), written originally for an American audience, about the ways in which a middle class elite quietly advance their own children at the expense of other people’s. Those growing ever angrier at where the referendum is leading us may however prefer Nick Clegg’s How to Stop Brexit (Bodley Head), a short, sinew-stiffening guide for anyone whose New Year’s resolution is to do exactly that.

In My Life, Our Times (Bodley Head), Gordon Brown attempts to put the record straight about the last Labour government and defend his part in bringing the world back from the brink during the 2008-09 financial crisis. The book suffers from some occasionally jaw-dropping absences of self-awareness, and a certain magisterial self-absorption. But Brown’s frustration that Labour could not hang on to power long enough to tackle deeper issues exposed by the banking crash is palpable.

The surprise delight of the year for me, meanwhile, was the Washington Post reporter Souad Mekhennet’s I Was Told to Come Alone (Henry Holt). It’s ostensibly a book about journalism, from a woman who covered the rise of Al Qaida, the Arab spring and then Daesh via a remarkable and at times personally risky series of interviews with extremists. But it’s also a highly readable primer on the forces that gave rise to extremish, and an insight into the complexities of immigrant identity and loyalty.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd