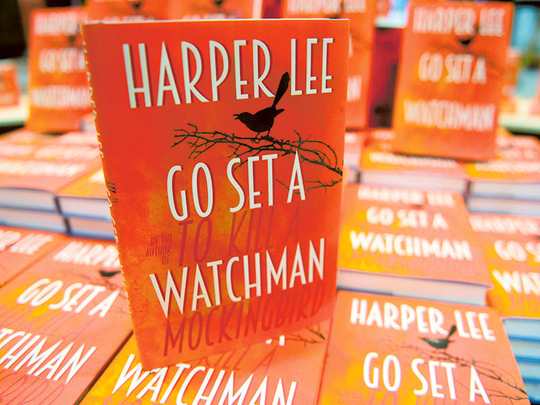

This was the year that fiction made headlines. To Kill a Mockingbird was a world-altering debut followed by 55 years of silence. In February it was announced that an earlier manuscript had been unearthed in Harper Lee’s archive, and in July, Go Set a Watchman (Heinemann) was published amid a storm of controversy about elder abuse, literary intentions and whether the book was actually any good.

Lee herself called it a “pretty decent effort”: set 20 years later than Mockingbird, it sees an adult Scout returning to her deep south hometown to visit her ageing father Atticus, depicted here as a crotchety racist rather than the saintly crusader of Mockingbird.

Unsurprisingly, the book turned out to be an apprentice work, containing in Scout’s childhood memories the germ of the classic for which she’ll be remembered, but it ignited a fascinating debate on the place and portrayal of racism in both books, as well as about the magic and hard graft of novel writing.

It wasn’t the only book to be front-page news. A Discworld novel has been a yearly treat for decades, but following Terry Pratchett’s death in March from the “embuggerance” of early onset Alzheimer’s disease, The Shepherd’s Crown (Doubleday) marks the final visit to his fantasy world.

Starring young witch Tiffany Aching and some enjoyably nasty elves, it ruminates on mortality and morality and is a fitting finale to a career that demonstrated, over and over, the literary merit of fantasy and comic writing.

There is a fantastical flavour to Kazuo Ishiguro’s first novel in 10 years, The Buried Giant (Faber), a deeply strange and powerful work set in a misty, semi-mythical England of dragons and ogres, with Saxons and Britons living in uneasy peace. An old couple undertake an uncertain quest, on which they are joined by an ageing, battle-weary Sir Gawain, as Ishiguro pursues his customary themes of memory and forgetting, national narratives and individual identity.

Overlooked for the Man Booker, for me it was one of the standouts of the year.

Some mighty literary projects reached their conclusion in 2015. The Story of the Lost Child (Europa) is the fourth and final volume in Elena Ferrante’s series of Neapolitan novels, which explore female friendship and creativity against the tumultuous backdrop of Italian political violence and changing social mores. The books are startling, all-consuming, dense with plot and psychology — buy the set and begin with Elena and Lila’s childhood in My Brilliant Friend; it’ll be a long time before you come up for air.

Autumn’s Golden Age (Mantle) followed hard on the heels of spring’s Early Warning to round off Jane Smiley’s dazzlingly expansive Last Hundred Years trilogy, which follows one American family from 1920 over the horizon of the near future; while Amitav Ghosh’s trilogy about the 19th-century opium trade concluded with the exuberant Flood of Fire (John Murray). English readers of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s six-volume autobiographical series, meanwhile, have only reached book four: Dancing in the Dark (Vintage) finds the 18-year-old Knausgaard teaching in a remote school in Norway, burning with shame and ambition, desperate for literary and sexual awakening.

There were new books from several literary grandees. Milan Kundera and Umberto Eco published slim, slightly whimsical volumes, while Salman Rushdie’s rollicking Arabian Nights-style fantasia Two Years Eight Months and Twenty Eight Nights (Jonathan Cape) is an energetic return to form pitting reason against religious zeal.

Margaret Atwood’s The Heart Goes Last (Bloomsbury) knits capitalism, desire and corporate control into a surreal dystopia; American teen favourite Judy Blume’s adult novel In the Unlikely Event (Picador) is based on a series of inexplicable plane crashes during her own adolescence; and Erica Jong updated her 1970s feminist classic Fear of Flying to riff on death rather than sex in Fear of Dying (Canongate). We also had the first novel in five years from Jonathan Franzen, Purity (4th Estate), about family secrets and internet leaks.

The vogue for sequels and reboots long ago crossed over from film into fiction. Two followups worth picking up on were Kate Atkinson’s A God in Ruins (Doubleday), a sister volume to 2013’s Life After Life, and Jonathan Coe’s Number Eleven (Viking), billed as a sequel to his 1994 political satire What a Carve Up!

Atkinson’s novel time-hops around the life of Teddy, brother to her heroine Ursula in Life After Life, and contains some extraordinary war writing about the RAF bombing raids. Number Eleven has less in common with Coe’s classic than fans might hope for, but the combination of nostalgic yearning and contemporary fury — targets include the moral vacuum in politics, the impunity of the super-rich and the lazy cruelty of reality TV — makes this a fascinating companion piece to his best-loved work.

Anne Enright is at the top of her game in The Green Road (Jonathan Cape), a globe-trotting, kaleidoscopic portrait of Irish siblings and their difficult mother, as is Sarah Hall in The Wolf Border (Faber), the beautifully written tale of a loner’s journey into motherhood as she oversees the reintroduction of wolves into the wild in England. Enigmatic heroines are also the order of the day in Rupert Thomson’s Katherine Carlyle (Corsair), an unnerving, unputdownable road trip from Rome to the far north, narrated by a young woman who, through the wonders of science, was “born twice”, and Andrew Miller’s The Crossing (Sceptre), another lone-woman-on-a-journey novel that keeps the reader guessing.

There was some wonderfully dark comic fiction published in 2015. Miranda July’s brilliantly uncomfortable The First Bad Man (Canongate) is an oddball’s subversive quest for love and babies; Nell Zink’s spiky two-novel package Mislaid and The Wallcreeper (4th Estate) shows her to be a true original; and Steve Toltz’s Quicksand (Sceptre), starring Australia’s unluckiest man, is extravagantly funny and sad by turns.

In a year of vast and vastly hyped American novels, the one to rule them all was Hanya Yanagihara’s Booker favourite A Little Life (Picador), which divided readers into the ecstatic and the exasperated. The gems in a strong Booker lineup were Sunjeev Sahota’s timely and humane novel about Indian immigration to Britain, Year of the Runaways (Picador), and the eventual winner, Marlon James’s multi-voiced saga of drugs and corruption in Jamaica, A Brief History of Seven Killings (Oneworld).

Translated treasures included South Korean author Han Kang’s The Vegetarian (Portobello), a transformative fable about desire, frustration and individual will; and Mexican Yuri Herrera’s Signs Preceding the End of the World (And Other Stories), in which a young woman’s perilous journey to the US in search of her brother involves other border crossings that are mythical, psychological and metaphysical.

Finally, 2015 saw the welcome rediscovery of an overlooked American great, and the best book yet from an Irish rising star. Lucia Berlin’s short stories of blue-collar life, written from the 1960s to the 1990s, are collected in A Manual for Cleaning Women (Picador).

Direct, unsentimental, viscerally frank, they take in drink and drudgery, yearning and delight, in a voice both urgent and unique. And Kevin Barry’s elusive, freewheeling Beatlebone (Canongate) introduces us to John Lennon at the height of his fame as he takes a solo trip to the west of Ireland, hoping to visit his very own island off County Mayo and jumpstart his creative powers with a spot of primal screaming. Soaked in liquor and sarcasm, bad weather and self-doubt, the book is spooky, profound and extravagantly enjoyable: a record and a reminder of the fact that the wildest journeys are the inner ones.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd