By Jane Harris, Faber, 320 pages, £14.99

Jane Harris’s first two historical novels showcased the voices of unsung, socially disadvantaged characters: a young Irish immigrant in The Observations, an elderly Victorian spinster in Gillespie and I. Harris is an empathetic and intelligent writer, with an instinct for the delicate alchemy that produces page-turners.

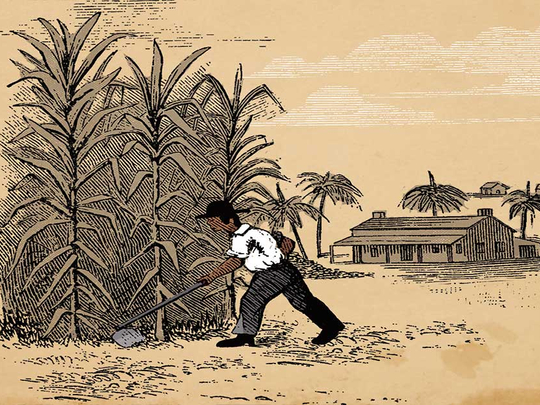

In her third novel, based on a true story, Harris takes us to 1765 and the voice of Lucien, a “mulatto” slave who is “thirteen or fourteen or thereabouts”, and has been brought over to Martinique from his native Grenada. Lucien works tending livestock on a plantation run by French friars. His only family is older brother Emile, who works “a long day hike away”.

Lucien is a vivid character from the first page: when called from the cows to his master’s side, he responds to the slack-jawed messenger with the delicious scorn of youth (“he had froth at the corner of his mouth from which signs I deem him to be of no startling intelligence”), while exhibiting a soft centre in regard to the animals (“She had the fluffiest, most velvety ears of any cow you did see”).

The summons is important: Father Cleophas wants the brothers to undertake a highly suspect mission. They must return to Grenada and smuggle back 42 slaves, former property of the friars, but claimed by English invaders when they took over that island two years ago. Celeste, Emile’s former sweetheart, is among them. Cleophas says the endeavour is blessed by the English governor of Grenada, but also warns that the plantation overseers strongly contest their claim.

Harris’s decision to cast this as an adventure story — tremulous tone and all — seems intended to express the joie de vivre of our young protagonist. Her gentle beginning barely nods to slavery’s barbarity. What with the humorous references to the eccentric “dummie” of a ship’s captain, Bianco, who swigs rum as he whisks them across the sea, and with Lucien’s hero-worship of Emile and Emile’s longing for Celeste, readers may feel as if they’re on a jolly themselves. By the time they reach Grenada, and begin to convince their old friends to return with them, I wanted to scribble a huge note in the margin as a reminder that slaves have been sent to gather other slaves, and that the 289-kilometre trip from Grenada back to Martinique would be a journey into more slavery.

Some might argue that Harris shows deliberate restraint so that the eventual violence hits more strongly, and certainly when she does describe the physical and psychological horrors she pulls no punches. Emile and Lucien witness the atrocities of British rule, and must face what has happened to Celeste since they left. Mounting fear becomes visceral. By the time we reach the story’s thundering and inevitable climax, I had nearly forgiven this early restraint — nearly. I still think it’s a tactic that compromises authenticity and tone for too long. The violence of slavery was unremitting. There was no respite; it permeated all aspects of life, and was meant to do so.

Viet Thanh Nguyen, in an article in the Los Angeles Times about the complex issue of white writers creating black characters, says it is “not simply an act of culture and free speech, but one that is enmeshed in a complicated, painful history of ownership and division”. I think Harris understands that complexity; and she does a heartfelt job of evoking this time and place. Her research is clearly extensive and her characters are well rounded. The language of the period is sure and consistent. But there are blind spots. When the brothers meet their old friend Chevallier, he tells them whipping has been cut back because it impedes productivity; “other punishment” is being applied. When Emile presses him to explain further, Chevallier demurs to protect Lucien: “Hard to say — bad things.” Harris wants this journey to sweep away Lucien’s innocence, but his back has already been torn by the whip. Lucien says it himself: “I am a man already.”

As I climbed through Grenada’s lush vegetation with Lucien, I couldn’t help but think of Harris on my bookshelf, alongside Colson Whitehead’s searingly original Underground Railroad, Marlon James’s uncompromisingly brutal The Book of Night Women, and Caryl Phillips’s wonderfully characterised Cambridge. It is appropriate to ask what an author brings to an established canon. By the time I dared to consider the spine of Toni Morrison’s Beloved leaning against Blood Sugar, the game was up. Harris spends sentences on moments that Morrison would explore for pages; many readers will find this novel a suitably affecting introduction to this brutal subject and its themes, but for me the work of those authors who have gone before Harris will eclipse Blood Sugar. This is a tale that has already been told, in so many complex, beautiful ways and will be told again, not least by writers who will not be read or promoted as widely as Harris. Pointing this out may be unfair to a writer who has worked so hard — but such risks arise, when one is ambitious and steps into this particular fray.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd

Leone Ross’s Come Let Us Sing Anyway is published by Peepal Tree.