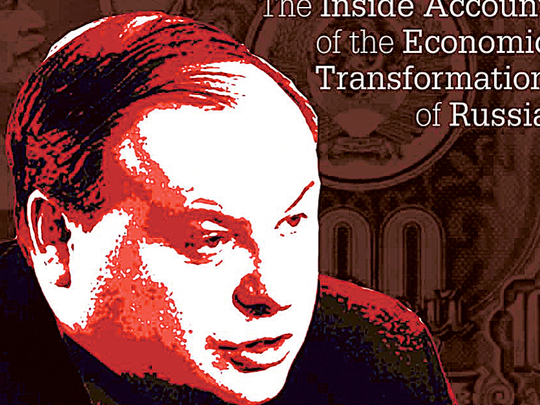

Gaidar’s Revolution: The Inside Account of the Economic Transformation of Russia

By Petr Aven and Alfred Kokh, I.B. Tauris, 352 pages, $50

Towards the end of 1991, Andrei Nechayev dropped into the supermarket near his Moscow home. He wanted something to eat — but the surreal sight that greeted him dashed his modest plan. “There was absolutely nothing in the store at all,” he recalls in “Gaidar’s Revolution”. “But someone must have thought it was not good to have the shelves empty, so they filled all the shelves with jars of adjika hot sauce. That was it. A huge supermarket, 7:00 or 8:00 pm on November 7, 1991. The centre of Moscow.”

It was a revelatory moment for the man just appointed Russia’s deputy economics minister, one that brought home the magnitude of the task confronting the government of which he was part.

Those “young reformers” — whose administration assembled itself almost by chance in the liberal, pro-Western surge that accompanied the disappearance of the Soviet Union — lived in a phantasmagoric world. They forced through vast reforms on a sclerotic, bankrupt economy at a fantastic pace. They lived through hectic, 16-hour days, where the benefits of their liberalisations were often a matter of faith — until partly freed prices stimulated a market reaction, and the shops began to fill again.

The leader of this team of men (all men) was Yegor Gaidar, a short, plump economist who had been born into the Soviet nomenklatura — his father was an admiral and Pravda commentator, while his Red Army commander grandfather had died fighting the Nazis — yet had, since his youth, been preoccupied with the question of how to reform his country.

At 35, he was among the oldest in the cabinet room; he had the natural authority of the quickest brain and, more important, willpower and a readiness to assume responsibility. These qualities sustained him through a year in which he was “acting” prime minister of a country in several kinds of crises, and then through further service as first minister for the economy and a constant adviser to President Boris Yeltsin.

Petr Aven and Alfred Kokh, themselves former young reformist ministers, have sought to honour his memory — Gaidar died nearly six years ago — by interviewing at length several members of the “Gaidar gang”, teasing out their memories, exploring the choices they made, lamenting the might-have-beens, underscoring the achievements.

It works well at times: the personal recall of incidents, problems and conflicts fills out journalistic and academic accounts with blasts of human frailty and courage, spite and generosity. At other times, Aven and Kokh allow — or encourage — their interlocutors to go too far down paths strewn with old enmities, slights and sackings.

At the end, they slip in an interview with the 85-year-old James Baker, US Secretary of State from 1989 to 1992. Aven presses Baker hard on why the US didn’t give Russia more financial aid, saying it could have allowed them to embed liberal reforms. Baker didn’t think so, and still doesn’t.

The Gaidar gang were not all friends. They argued fiercely, but Gaidar’s convictions and courteous yet insistent public style kept them, for a while, together. I was the first foreign correspondent to discover that they were drawing up an economic programme for the country and that they were likely to be appointed to implement it: I drove on a Saturday evening to an estate of government dachas some 40 kilometres from Moscow, and waited for Gaidar to brief me, next to the conference room in which the gang were sprawled around a large table with notepads before them, their discourse leavened with the bursts of laughter of young men on the eve of a great adventure.

In office, though, they quickly dubbed theirs a “kamikaze government” and thought, perfectly seriously and with solid reason, that they would end up in prison, or be shot.

Gaidar was their leader, but Yeltsin, president from 1991 to 1999, was their boss. A radical convert to liberal democracy and free markets, he had at the same time all the instincts of a party-appointed first secretary of an industrial region (Sverdlovsk, 1976-85) and a deep understanding of the reflexes of those who had kept the Soviet show on the road. He trusted Gaidar, even as he jerked him in and out of government, now in to surmount this crisis, now out to placate that anti-reform faction.

Without preparation, with scholarly habits and with no executive experience beyond an academic department, Gaidar became prime minister of a country in which war was breaking out along the Caucasus and in Moldova, in which defence cuts reduced arms procurement to one-eighth of the Soviet level, in which lines of elderly women would stand in sub-zero temperatures outside metro stations selling frames which had held family photographs.

That he, with Yeltsin, shouldered this burden is testament to his great courage. I remember going with him one December to Vorkuta, the city in the far north built as the hub of an archipelago of prison camps — where, at a cheery celebration of the founding of the city that ignored its grim past, he stood up to call for that savage history to be remembered, and for the legions of zeks worked to frozen death to be honoured. He was hissed and jostled as he left. It was a glimpse of what he and his colleagues faced every day.

Fuelling the hostility was the fact that their appointment, and their actions, coincided with economic catastrophe and seemed so obviously responsible for it. More, the privatisation of the economy, done at breakneck speed, hugely benefited those savvy enough to know the real value of the assets and able to organise their purchase: property passed from belonging nominally to the people to being owned legally by oligarchs.

But the reformers’ overriding imperative was to take economic power out of the hands of the state, fearful that if that was not done, a revolt against liberalisation would gather and win, and they were probably right in that.

The young reformers, as Aven and Kokh stress, were not dissidents: they were mainly highly educated economists who saw that the Soviet system was finished, and that the market and, with it, democracy had to be embraced. The youngest of them are now in their 50s, and most have made their peace with the Putin era, occasionally criticising it but usually only mildly.

Aven himself has done best financially: with a personal worth estimated by Forbes at over $5 billion (Dh18.4 billion), he is chairman of Russia’s leading private bank, Alfa-Bank. Nechayev went on to become president of the Russian Financial Corporation Bank (until 2013), while Anatoly Chubais, who oversaw the initial privatisations and stuck with Yeltsin the longest, is chairman of Rusnano, the state-owned nanotechnology corporation.

Yet Kokh — of German origin, with the great patronymic of Rheingoldovich — moved to Germany last year, saying he feared for his life under President Vladimir Putin’s government. Last autumn he organised a meeting in Bavaria for a number of the young reformers; among the attendees was the former minister Boris Nemtsov, who was murdered in Moscow in February.

As for Gaidar, the man at the centre of the liberal revolution, he died in December 2009, aged 53. I chaired a seminar with him at the Trento Economics Festival that year, and he was distracted and withdrawn. For him, his political life had been a failure, though that self-evaluation was far too harsh.

The leading economic radicals of the post-communist period — Leszek Balcerowicz in Poland, Václav Klaus in the Czech Republic, Mart Laar in Estonia — dealt with economies much smaller and much less brutally marshalled into a state plan, and with a people generally happy to be rid of the Russians.

Gaidar was faced with leading these Russians towards the market and democracy: his aim, as his friend Carl Bildt, Sweden’s prime minister during Gaidar’s term of office, puts it in an afterword, was for Russia to become “a prosperous, democratic, leading great European power living in harmony and cooperation with its neighbours”. That Gaidar couldn’t achieve that immense task may have contributed to his early death; that it ever looked like a possibility is much due to him.

–Financial Times