An Untamed State

By Roxane Gay, Grove Press, Black Cat, 368 pages, $16

My introduction to Haiti came in the form of a woman. It was at the height of the Haitian refugee exodus of the early 1980s, when tens of thousands fled blistering poverty and political tyranny for the relative safety of the United States. We waited to greet her, my father and I, at Houston airport — her flight ticket having been arranged by the civil rights organisation where my father worked at the time. She was one of the last off the aircraft, a thin woman in her twenties, dark-skinned like me, polite and terrified.

My father was highly sensitive to the realities of a woman travelling to a foreign country alone. He hoped my presence would put her at ease — that if she saw him as a father, she would fear him less, could safely assume that a man with his eight-year-old child in the car wouldn’t pull over in a dark alley and take advantage.

Over the span of a year, I made half a dozen of these trips with my father, picking up desperate women at airports and bus stations, some with children in tow, but most of them alone; childlessness making it easier to reinvent one’s life from scratch.

The memory left me with two distinct impressions: first, the threat of danger any woman faces when alone with a strange man; and, second, an image of Haiti as a wasteland, a country to which no one would ever willingly return.

But nothing could have prepared me for “An Untamed State”, the breathtaking debut novel by “Bad Feminist” author Roxane Gay. The plot of this tightly wound psychological thriller is deceptively simple, centring not on a woman’s flight from Haiti, but a native daughter’s return to a country that has too frequently been viewed solely through the lens of political turmoil and poverty.

To be sure, that Haiti exists in this book too, but usually it’s kept safely on the other side of the razor-topped walls that surround a wealthy seaside compound in Port-au-Prince, a palace fit for a self‑made king. It is just outside these concrete walls, at the gates to her father’s sprawling estate, that Mireille Duval Jameson is kidnapped at gunpoint in front of her husband and infant son by gangsters seeking a seven-figure ransom from her rich father as an ill-conceived attempt at retribution for the economic inequality in the country at large.

It is a crime carried out in service to a messy political ideology, one that conveniently makes no allowance for the humanity of women.

Over the course of 13 days, Mireille suffers mercilessly at the hands of her kidnappers, an ordeal Gay describes in dizzying, heart-stopping prose. But when Mireille tells “the Commander”, the leader of the men who have taken her, that neither she nor her family created Haiti’s problems, he counters with the accusation: “You are complicit even if you do not actively contribute to the problem because you do nothing to solve it.”

They are both right, of course, and part of the novel’s power resides in the existential question: to what degree are we our brother’s keeper? What, if anything, do the wealthy few in Haiti owe to the many poor?

The Commander’s rage is not really against Mireille, a woman raised in the United States by her Haitian immigrant parents, but against her father, Sebastien Duval, an engineer who made a fine living in the US: enough to educate three children, but not enough to feel true agency over his fate in a foreign land. Though his American-born children are able to create fulfilling lives in the US, Sebastien is unable, or unwilling, to resist the pull of home. He makes a triumphant return to Haiti, where he builds an enormously profitable construction company.

Gay is never clear whether Sebastien’s wealth is ill-gained, a result of the corruption that is rumoured to run rampant in the country. But the book suggests that in a country as poor as Haiti, perhaps wealth is inherently criminal. What is clear is Sebastien’s reluctance to negotiate with his daughter’s captors — to give away his life’s savings to terrorists who will stop at nothing to bring down men like him.

Because the novel is told in the past tense, we know from the outset that Mireille will physically survive her ordeal, and in this way, Gay turns the thriller form on its head. Murder is not the ultimate crime here. The novel’s suspense is instead built around the question of what one woman’s body can endure as punishment for her father’s supposed misdeeds.

Mireille’s body becomes the landscape, the “untamed state”, on which a political war is waged by men who want to use it for their own ideological purposes. Told in language that is spare and unflinching in its portrayal of sexual and spiritual violence, Mireille’s story is a harrowing nightmare; yet it is also a gripping and surprisingly hopeful tale.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd

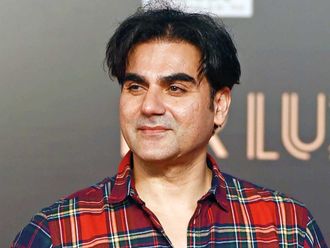

Attica Locke’s latest book is “The Cutting Season”.