At 7.30am on July 1, 1916, whistles blew and the first waves of 120,000 British and empire assault troops climbed out of their trenches, or rose from prone positions in no-man’s land, to attack 25 kilometres of multilayered German defences. Burdened with 31kg of kit, the soldiers had been ordered to walk until they were 18 metres from the enemy trench, for fear they would exhaust themselves and lose formation.

Ahead of them lay belts of German barbed wire, many of them still intact despite an unprecedented seven-day bombardment of 1.5 million shells. The race was on. Would the slow-moving attackers reach the German front line before the defenders had emerged from deep dugouts and manned their machine-guns? In most cases, the answer was no. Men were mown down like corn. By nightfall, British gains were restricted to five kilometres of the German front line in the southern sector. The neighbouring French advanced to a similar depth. But at no place had the German second line of trenches — part of the original objective — been captured, let alone the third.

The cost was 57,470 casualties (including 19,240 men killed), just under half the total engaged. It was, and still is, the bloodiest day in British Army history.

The attacks would continue for four-and-a-half months, advancing the Allied line just 11 kilometres. Total casualties were more than 600,000 for both sides. The battle, not surprisingly, is Exhibit A for the “Lions led by Donkeys” school of historians — led by the late Alan Clark — who claim that courageous and inexperienced British soldiers were needlessly sacrificed by incompetent generals.

More recently the thesis has been challenged by the “learning curve” scholars — John Terraine, Gary Sheffield and Simon Robbins among them — who argue that the Somme and subsequent battles were a necessary, though bloody and regrettable, rite of passage for an Edwardian army learning to fight an industrial war. William Philpott has gone even further, describing the Somme as the “military turning point of the war” and a “genuine moral victory in adversity over circumstances, the elements and the enemy”.

So, do the latest batch of histories, published to coincide with the centenary of the battle on July 1, add anything to the debate? And after hundreds of previous books, is there any new material to reveal? The answer to both questions is a resounding yes.

|

|

Somme: Into the Breach |

By Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, Viking, 656 pages, £25 |

Hugh Sebag-Montefiore’s magisterial “Somme: Into the Breach” is the fruit of eight years’ labour and it shows. He draws on previously unpublished sources from Britain, Australia, New Zealand and Germany to reconstruct the story of the tragic battle in almost forensic detail. So original is the material, and so inventive is Sebag-Montefiore’s approach — telling each stage of the fight from the perspective of both the combatants and their families back home — that this well-known tale is rendered strange again.

Some heartbreaking chapters cover the legendary Australian capture of the village of Pozieres in late July, at a cost of 5,200 casualties. As the shell-shocked survivors withdrew, they were likened to “men who had been in hell. Almost without exception, each man looked drawn and haggard, and so dazed they appeared to be walking in a dream”. Many of the dead simply disappeared, and it took the family of one Australian officer more than 16 months to establish that he had been blown to pieces in a follow-up attack on July 28, thus enabling them to wind up his estate and move on with their lives. His brother blamed his death on “the incompetence, callousness and personal vanity of those high in authority”.

But if Sebag-Montefiore’s use of first-hand accounts is exemplary, so too is his historical judgment. Many historians insist the British plan was an “unhappy compromise” between Sir Douglas Haig, the commander-in-chief, who hoped for big leaps forward and even a major breakthrough, and Sir Henry Rawlinson, the commander of the Fourth Army, who preferred limited gains of one trench system at a time, followed by a pause while artillery was moved forward (a tactic known as “bite and hold”). In fact, says Sebag-Montefiore, Haig’s tactics predominated because Rawlinson owed him for saving his job a year earlier.

“Haig was able to use his hold over Rawlinson to dominate him, and to require him to fight the Somme battle in the way he desired.” The author condemns both Haig and Rawlinson — rightly in my view — for failing “to give sufficient weight to what they were told by their artillery experts, and neither applied common sense when planning their original attacks”.

But on occasions, he writes, Haig was “able to make the British Army perform efficiently”, as with the second Australian attack on Pozieres Heights. The battle was punctuated by a number of other successful assaults that were never properly exploited. These limited gains, writes Sebag-Montefiore, were largely thanks to the “indomitable spirit of the British, Canadian and Australasian infantry”. Though unable to break through the German lines “other than superficially”, the “Big Push” wore out the German army and forced it to abandon its offensive at Verdun.

If not a British victory, it was “the beginning of the German slide towards defeat”. Written with great style and sensitivity, superbly illustrated with many original plates and beautifully drawn maps, Sebag-Montefiore’s brilliant new study will set the benchmark for a generation.

|

|

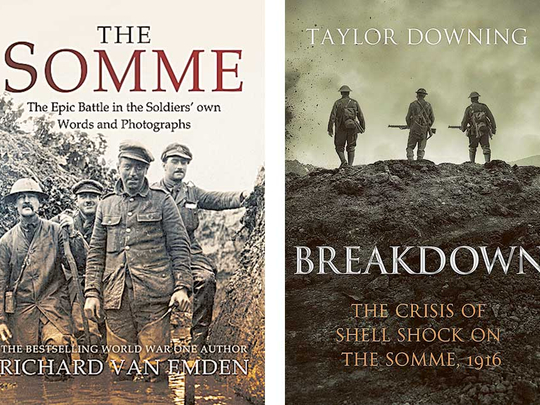

Breakdown: The Crisis of Shell Shock on the Somme, 1916 |

By Taylor Downing, Little, Brown, 416 pages, £25 |

Taylor Downing’s “Breakdown: The Crisis of Shell Shock on the Somme, 1916” concentrates on the official response to the epidemic of shell shock, or combat stress, that occurred during the 140-day battle, the most intense and long-running fight in the British Army’s history. It was because of this “prolonged fighting and heavy bombardment” that so many men succumbed to nervous disorders.

Officially there were 16,000 shell shock victims during this period; Downing puts the true figure closer to 60,000, or the equivalent of three whole infantry divisions. Faced with such a severe drain on their manpower, the authorities responded by massaging the figures and refusing to allow most of the sufferers to return home for treatment. Some were among the 309 British and Commonwealth soldiers executed for military offences. “Instead of receiving sympathy and understanding for the terrible mental injuries they suffered,” writes Downing, “they were put up against a wall and shot.”

Yet the advances made in the treatment of shell shock in Britain had two positive outcomes: they showed that anyone could suffer from mental ill health and that, contrary to the opinion of the Victorians, it was possible to be cured of mental disease. “Out of the immense suffering of the wartime years,” argues Downing, in this humane and intensely moving book, “came at least some progress.”

|

|

The Somme |

By Richard van Emden, Pen & Sword Military, 400 pages, £25 |

Richard van Emden’s “The Somme” is essentially an oral and visual history, and so largely avoids the historical debate about what went wrong and who was to blame. But it includes much new material, particularly in the form of photos taken by British soldiers on their own illegally held cameras, and sets the battle in its proper context by covering the entire 20-month period that the British Expeditionary Force spent on the Somme. It deserves to be read.

Each of these books is proof that history constantly evolves; that there’s always something new to say. They remind us that the Somme was not the pointless slaughter of popular myth, and that many of the participants thought the sacrifice worthwhile. “Whether I am to emerge from this show I do not know,” wrote a young British officer killed in the final attack. “Surely it is a life fulfilled if one dies young and healthy fighting for one’s country.”

–The Telegraph Group Limited, London 2016