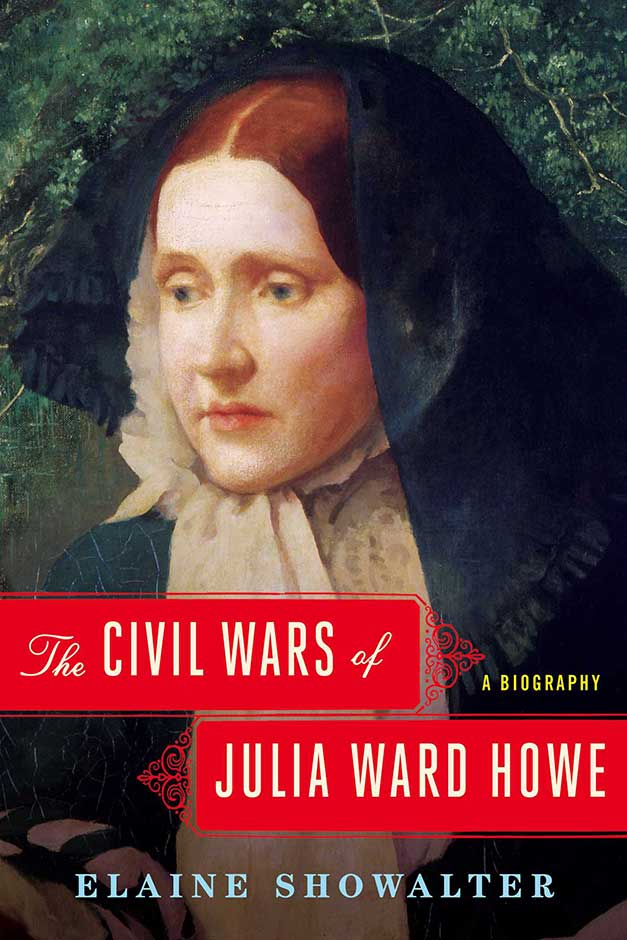

The Civil Wars of Julia Ward Howe: A Biography

By Elaine Showalter, Simon & Schuster, 320 pages, $28

“It needed a very serene or a very powerful mind to resist the temptation to anger,” Virginia Woolf wrote in 1929 in an essay about 19th-century women writers. A woman might start out writing about one thing or another but, before she knew it, she’d find herself “resenting the treatment of her sex and pleading for its rights”. This was a pity, Woolf thought, and a trap she hoped women were on the verge of escaping.

Julia Ward Howe is a good illustration of Woolf’s argument, and also of its limits. Howe started out as a poet and a critic — she wrote about Goethe and Schiller — and she ended up writing about the right to vote. In between, she got very angry. This wasn’t much good for her poetry, but honestly, it’s hard to blame her.

Julia Ward was born in New York City in 1819, three days after Queen Victoria. In 1843, she married Samuel Gridley Howe, a doctor and the first director of the Perkins Institution for the Blind. She’s chiefly known for one thing, which vastly underrates and wildly misrepresents her. In 1861, she wrote the lyrics to the crushingly beautiful “Battle Hymn of the Republic”. In portraits from her later years, her head is draped in lace. By the time she died, in 1910, she was known as the “Queen of America”, a dear and dainty old lady. It’s as if her whole life has been hidden beneath a lavender-scented doily.

In a riveting and frankly distressing new biography, the distinguished critic Elaine Showalter insists that Howe, who was born in the same year as Walt Whitman, had “the subversive intellect of an Emily Dickinson, the political and philosophical interests of an Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and the passionate emotions of a Sylvia Plath”.

The problem was her world and, more particularly, her husband. His star student, Laura Bridgman, deaf and blind, was utterly devoted to him; it was just this sort of devotion that he desired in a wife. He told Julia he wanted her kept in a chrysalis, declaring that if she ever emerged and grew wings, “I shall unmercifully cut them off, to keep you prisoner in my arms.” He was 18 years older than she was — “The Dr. calls me child,” Howe told her sisters.

Soon Mrs Howe was pregnant. “Only a year ago, Julia was a New York belle,” her husband wrote to Charles Sumner, who served as best man at his wedding. “Now she is a wife who lives only for her husband and a mother who would melt her very beauty, were it needed, to give a drop of nourishment to her child.” That’s not how she saw it. “Are we meant to change so utterly?” she asked her sister Louisa. “In giving life to others, do we lose our own vitality, and sink into dimness, nothingness, and living death?”

Howe loved her children; when one of them died of diphtheria, she dreamt every night of nursing him in the dark. But she worried that she didn’t care for her sons and daughters in quite the way she was supposed to. “I am alas one of those exceptional women who do not love their children,” she once wrote, then crossed out “do not love” and wrote instead “can not relate to.”

The Howes moved into the Doctor’s Wing of the Perkins Institution for the Blind. She grew disgusted with her husband’s obsession with incapacitated females. She wrote a poem, “Anne Sextonian”, about what he looked for in a woman:

“She has but one jaw,

Has teeth like a saw,

Her ears and her eyes I delight in:

The one could not hear

Tho’ a cannon were near,

The others are holes with no sight in.”

At home with her young children and pregnant more often than not — “My books are all that keep me alive” — Howe was miserable. “My thoughts grow daily more insignificant and commonplace.” She wanted to use ether during childbirth. Her husband forbade it, declaring that women need discipline: “The pains of child birth are meant by a beneficent creator to be the means of leading them back to lives of temperance, exercise and reason.” In 1847, Howe confided to her sister that her life had become unspeakable, unbearable: “You cannot, cannot know the history, the inner history of the last four years.”

Secretly, she began writing a novel, “the history of a strange being, written as truly as I knew how to write it.” She never tried to publish it. The manuscript, with its first page and title missing, was deposited at Harvard’s Houghton Library in 1951 by Howe’s granddaughter, amid “10 boxes of unsorted prose manuscripts and speeches”. Possibly the first person ever to read it was Mary H. Grant, a graduate student who discovered it in 1977 while on a five-day research trip to Cambridge, during which she left her baby with a friend who had three children of her own. Happening upon Howe’s unpublished and fragmentary manuscript was thrilling but also frustrating, Grant later wrote, “because it was going to take hours of precious research time to try to make sense of this wandering document when I had so little babysitting time available in which to work”. Howe would have understood.

The novel was published in 2004, brilliantly edited by the Howe scholar Gary Williams, as “The Hermaphrodite”. It tells the story of Laurence, a scholar who lives sometimes as a man and sometimes as a woman. A physician, asked to judge whether Laurence is truly either, says, “I shall speak most justly if I say that he is rather both than neither.”

Howe was influenced by George Sand, but “The Hermaphrodite” is also original, and remarkably daring. Her husband would not have approved, nor would hardly anyone else in antebellum America. “I make myself obscure in order not to shock other women,” she wrote in 1853, in a letter she never sent. In 1854, her first volume of poetry, “Passion-Flowers”, was published anonymously and without Samuel Howe’s knowledge. (The Boston publisher that issued it, and sold out the first edition, had rejected a manuscript written by her husband.) Many of the book’s poems are about her terrible marriage; others concern motherhood. In “The Heart’s Astronomy”, three children peer through the windows at their mother, who, “intent to walk a weary mile”, stomps “round and round the house”.

“They watched me, as Astronomers

Whose business lies in heaven afar,

Await, beside the slanting glass,

The reappearance of a star.”

She warns them not to mistake her for anything with so predictable an orbit:

“But mark no steadfast path for me,

A comet dire and strange am I.”

Nathaniel Hawthorne, asked what American books Europeans didn’t know about but ought to, named “Walden” first and then “Passion-Flowers”. He admired it but didn’t approve of it; the poems “let out a whole history of domestic unhappiness”, he thought. A few years later, he declared that “she ought to have been soundly whipt for publishing them”.

But, of course, she was soundly whipped. When he learnt the truth, her husband raged at her, said her poems “border on the erotic”, and then, following a long estrangement, demanded they resume sexual relations or else divorce. It was likely, she wrote to her sister, that he wanted to marry “some young girl who would love him supremely”.

Faced with the prospect of losing her children, she gave in: “I made the greatest sacrifice I can ever be called upon to make,” she confessed. When she became pregnant yet again, her husband considered putting the baby up for adoption if she disobeyed him.

Having accepted this dreadful bargain, Howe turned her attention to abolitionism. So did her husband, who supported John Brown. It was to the tune of “John Brown’s Body” that Howe wrote her Civil War anthem in 1861. “Writing ‘Battle Hymn’ was the turning point in her life, and its renown gave her the power and the incentive to emancipate herself,” Showalter writes. This is unconvincing. It seems more likely that the end of childbearing was the turning point in Howe’s life; she gave birth to the last of her six children in 1859, when she was 40. By the time she wrote “Battle Hymn”, her youngest was weaned, and Julia Ward Howe’s body was hers again.

“I have been married 22 years today,” she wrote in 1865. “In the course of this time I have never known my husband to approve of any act of mine which I myself valued. Books — poems — essays — everything has been contemptible or contraband in his eyes.” After the war, she fought for the passage of the 14th and 15th Amendments and then, in 1869, the year she turned 50, decided to focus her attention on women’s rights, joining advocates such as Lucy Stone and Susan B. Anthony, who, Howe wrote, “had fought so long and so valiantly for the slave”, and “now turned a searchlight of their intelligence upon the condition of woman”.

“Began my new life today,” she wrote on January 14, 1876, the day after her husband’s funeral. She had been married for nearly 33 years and would live another 34, as Showalter points out. The rest of Howe’s life was devoted to women’s suffrage. She served as president of the American Woman Suffrage Association and founded the Association for the Advancement of Women. Very little of this period, the last third of her life, is chronicled in Showalter’s biography. The book trails off as soon as Howe’s husband dies, and ends abruptly, as if this part of Howe’s life doesn’t much matter.

In a long and extraordinary career as a literary critic, one of Showalter’s most influential works is an essay called “Toward a Feminist Poetics”, published in 1979. In it, she argued that women’s writing should be sorted into three periods: Feminine, 1840-1880; Feminist, 1880-1920; and Female, beginning in 1920, by which time English and American women had gotten the right to vote and, presumably, women writers were freed, mercifully, to answer only to their art. To me, this history reads more like the stages of a woman’s life: a period of moody inwardness is followed by a period of angry political agitation that yields to a period of broadminded humanity. And then it begins all over again.

The history of the woman writer, Woolf thought, “lies at present locked in old diaries, stuffed away in old drawers, half-obliterated in the memories of the aged”. Showalter is part of a generation of exceptional scholars who found that writing and read it. Now what? In many ways, of course, it would be good to get past feminism. It can be tiresome to fight so old a fight. But that doesn’t mean the fight isn’t urgent. To live the life of the mind that Laurence could live only when dressed as a man, women are still asked to live as men and women who are mothers can still expect, more often than not, to fail. “A comet dire and strange am I.”

“She is no longer angry,” Woolf wrote in 1929. Oh yes she is.

–New York Times News Service

Jill Lepore is the David Woods Kemper ‘41 professor of American history at Harvard and a staff writer at “The New Yorker”. Her books include “The Secret History of Wonder Woman” and “Joe Gould’s Teeth”.