By Japanese standards, the Tokyo neighbourhood of Shin-Okubo is a messy, polyglot place. A Korean enclave that has attracted newcomers from around the world in recent years, its profusion of barbecue joints, pan-Asian street markets and halal butcher shops distinguish it in a country with a reputation for cultural homogeneity.

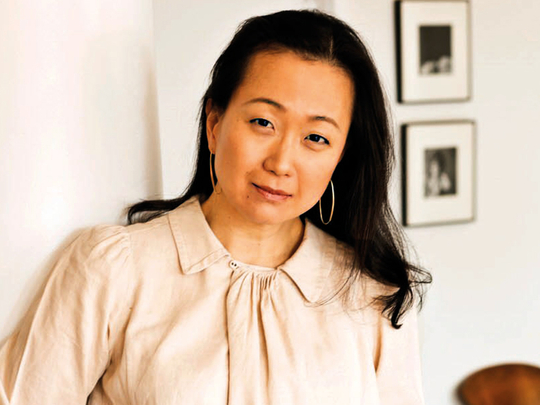

It is a fitting place to meet Min Jin Lee, a chronicler of the Korean diaspora whose sweeping yet intimate historical novel Pachinko is a finalist for this year’s National Book Award.

In two books published a decade apart, Lee, a 48-year-old American, has depicted the strivings and disappointments of Korean immigrants. The first, Free Food for Millionaires, from 2007, was set in her hometown New York City. For Pachinko, she spun the globe around, taking readers to the Korean Peninsula and its onetime colonial master, Japan.

“I have romantic ideas about home and what it should mean,” said Lee, who was born in South Korea and moved to New York — Elmhurst, Queens, to be exact — with her family at the age of 7.

Lee was speaking over spicy beef and kimchi at a restaurant in Shin-Okubo staffed by “zainichi” — descendants of the hundreds of thousands of Koreans who migrated to the Japanese islands during the first half of the 20th century, after Japan’s empire swallowed up the Korean Peninsula in 1910.

A mixed blessing

The migrants, whose story Lee tells in Pachinko, congregated in slums and performed mostly low-paid labour. Discrimination was rampant. The eventual liberation of their homeland at the end of the Second World War was a mixed blessing: No longer subjects of the Japanese emperor, Koreans lost the right to reside in Japan. Many had no homes or jobs to return to, so they stayed on anyway, prompting decades of wrangling over their legal status.

At the restaurant, a television showing K-pop videos hung next to a wall covered in white cardboard squares displaying autographs from celebrity customers — Korean food is popular in Japan, a paradoxical exemption from wider social prejudices. The waiter was a young man in his 20s. Lee cycled through English (her primary language) and Japanese (his) before settling on an imperfect middle ground of Korean.

The fictional family at the centre of Pachinko, the Baeks, grapples with problems common to transplanted people: material hardship, unwelcoming locals, the possibilities and limits of assimilation. For them, as for real-life zainichi, ethnic biases are compounded by colonial-era abuses and resentments. The physical similarities between Koreans and Japanese make “passing” as a member of the majority a tempting possibility, but a socially and psychologically risky one.

“Koreans have suffered from the discrimination that all immigrants face, plus an added dimension that comes from their having been colonial subjects,” said Masachika Ukiba, a professor of cultural anthropology at Nagoya University who has studied the zainichi population.

“Many of today’s zainichi are fourth-generation, so they’re hardly immigrants anymore. They are essentially Japanese,” Ukiba added. Outright discrimination has faded, he said, since the period depicted in Pachinko — the 1910s through the 1980s — but has not disappeared. Some bigotry has moved online, where trolls depict zainichi as “cockroaches” or fifth-columnists for nuclear-armed North Korea.

Lee spent nearly two decades conceiving, writing and rewriting Pachinko. The seed was planted in 1989, when, as a student at Yale, she attended a talk by a Protestant missionary who had spent time among the zainichi. Until then, she said, she had never heard of this branch of the Korean diaspora. Growing up in the United States, she was used to Koreans being viewed as hardworking and upwardly mobile, a model American minority. But many zainichi, she was surprised to discover, languished at the bottom rungs of Japan’s socioeconomic ladder.

“My level of research became a little neurotic,” she said. Although she was a Korean immigrant herself, she was entering a completely new world.

For ethnic Koreans in Japan, one route to economic improvement has been pachinko, a pastime derived from pinball. Played by millions of Japanese at noisy, smoke-filled halls, many of which are operated by zainichi, pachinko occupies a legal and social grey zone. The game itself is legal, but the gambling that inevitably accompanies it is not.

“Instead of banning it, Japan tolerates it but disparages the people who run it,” said Lee. She sees a parallel with Koreans’ place in Japanese society: deeply established, yet not fully accepted as legitimate members.

Lee’s family embodied the rosier American version of the Korean immigrant story.

In South Korea, her father had worked in marketing at a cosmetics company, but fears that the Korean Peninsula could erupt into another devastating war convinced him to leave. After arriving in New York in the mid-1970s, her parents operated a news kiosk in Manhattan, at Broadway and 31st Street. They soon upgraded to a wholesale costume-jewellery business, working and saving their way into the middle class and sending their three daughters to college.

Pachinko is a product of persistence. Lee discarded an earlier, more narrowly focused version of the novel, which she wrote in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Its original main character was Solomon Baek, an aspiring ethnic Korean investment banker who is subjected to bigotry and betrayal at a financial firm in Tokyo.

“It was boring,” she said — big on social themes but short on fully realised human characters and relationships. “I didn’t talk to enough people.”

The chance for a fresh start came in 2007, when her husband, a banker of Japanese descent, took a job in Tokyo. While there, she started looking for zainichi to interview — business people, pachinko parlour owners, bar hostesses.

“The first few were hard to get because I didn’t have introductions,” she said. “But then it was like the floodgates opened.”

Many of her subjects told love stories. Almost every Korean she spoke to, she said, had been rejected at some point because of their ethnicity. It was startling for an American: Even considering the United States’ unbridged racial divides, the zainichi seemed inescapably stamped by difference.

As she collected more stories, the novel grew in scope. It also became more feminine, she said. Lee expanded the role of Sunja, Solomon’s quietly tenacious grandmother, who leaves her Korean fishing village for Osaka as a young bride in the 1930s.

As an American, Lee was partly insulated from lingering bias in Japan against zainichi. But she still encountered casual ethnic stereotyping that surprised her. When she pointed out shoddy repair work at the apartment her family rented, an employee at the management company told her, “You Koreans are always complaining.”

At the church she attended, when she argued in favour of paying the homeless volunteers who cooked curry at the church soup kitchen, a Japanese fellow congregant said it was her “Korean blood” that caused her to make a fuss.

Lee finished her novel after returning to the United States. During her recent visit to Japan, she noted that while Pachinko has been picked up by publishers in more than a dozen countries, including Turkey and Poland, it has not yet found one in Japan.

Japan’s own literature contains prominent works by and about zainichi, many exploring similar themes of identity and history. Yang Sok-il’s semiautobiographical Blood and Bones, one of a number of popular books by Korean-Japanese authors, was turned into a movie starring the actor and director Takeshi Kitano in 2004.

Lee said she hoped that publishers would not be put off by an unsparing look at Japan’s still only partly resolved history by an American outsider.

“I do have love for Japan. At the same time, I have a complex relationship with Japan because I’m Korean,” she said. “But I think it shows the strength of a country when you can talk about the past transparently.”

–New York Times News Service