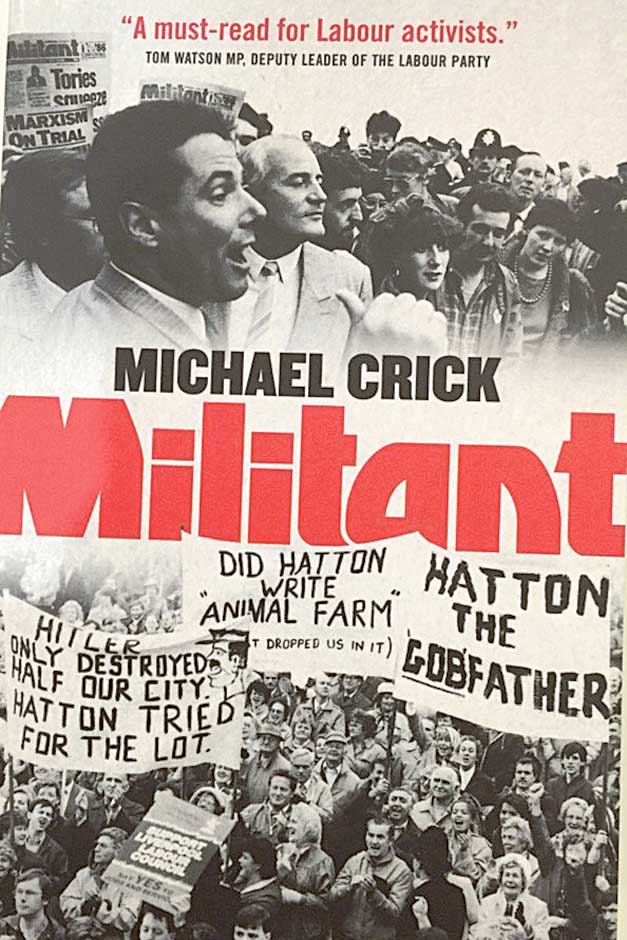

Militant

By Michael Crick, Biteback Publishing, 352 pages, £11

Panics about infiltrators are a Labour tradition. In a party made up of disparate elements from the start, in a country where the legitimacy of leftwing radicalism is rarely accepted by the media and wider establishment, it is hardly surprising that subversives, real and imagined, have regularly been spotted burrowing their way into Labour’s loose structures. During the 1920s, the party struggled to purge itself of communists, whom Lenin instructed to support Labour “as a rope supports the hanged”. Nowadays, the party’s right wing and its many press allies are in an almost perpetual froth about Labour being “taken over” by left-wingers, whether they are activists of the large new pressure group Momentum or even Jeremy Corbyn himself.

The troublemaking political journalist Michael Crick first published “Militant” in 1984, when the still-infamous leftwing sect was approaching the peak of its notoriety. In 1986 he produced an updated version, with the reds-under-the-bed title “The March of Militant”. Thirty years on, he has updated it again, with a foreword and afterword that seek to connect the sometimes startling, often caricatured history of Militant to Corbyn, both back in the 1980s and now.

The connections feel a bit oversold. “This is the story,” writes Crick, “of the Marxist, Trotskyist group whose presence inside the Labour party Jeremy Corbyn tried to defend.” Yet Crick has to concede early on that “Corbyn was never anywhere near being a member of Militant”. What’s more, his 1980s opposition to what he called an anti-Militant “witch-hunt” was widely shared on the Labour left. In the divided, feuding party of the time, purges and stopping purges were a preoccupation for many factions, as they sought to build useful alliances or weaken those of their enemies.

Similarly, the relative cordiality towards Corbyn from Militant’s current, less scarily named incarnation, the Socialist party — which sometimes calls him “Jeremy” in its newspaper, and hailed his election as leader as a “victory for the left” — may not be as significant as it seems. This approval has yet to solidify into cooperation, according to Crick: the Socialist party has “decided to see how Labour evolves”. Corbyn-bashers may find this book a disappointment.

But it is full of eye-opening facts for the rest of us. At its zenith in the mid-1980s, Militant, a revolutionary organisation that pretended to be merely a leftwing paper and its supporters — “in effect a secret political party”, in Crick’s words — had “probably more full-time workers ... than the Labour party itself”. The American embassy in London maintained a subscription to “Militant”. The faction had deep roots in prestigious universities: Sussex and Oxford, where one of Militant’s economic theorists, Andrew Glyn, a “member of the William and Glyn’s banking family”, taught David Miliband while “running the Oxford Militant branch”. Crick continues: “Both David and Ed Miliband,” whom Glyn also taught at Oxford after leaving Militant “around” 1985, “later described him as a huge influence”. Tantalisingly, Crick doesn’t spell out what that influence was.

The party had other strongholds across Britain: in places that were doing relatively well out of Thatcherism, such as Brighton and east London, and places that emphatically were not, such as Coventry and Liverpool. Militant’s first two MPs were elected in 1983, despite the defeat of the left as a whole at that general election. The same year, it effectively took control of Liverpool city council.

How did Militant achieve all this, when so many other British leftwing sects had failed? In a few clear, authoritative chapters, Crick shows that a key to its rise was appearing to be quite dull. One of its founders, Ted Grant, born with the perfectly Kafkaesque name Isaac Blank, was a seemingly bland, puritanical young South African Trotskyist, who emigrated to Britain in 1934. For the next four decades, with “Jelly Babies and gobstoppers [as] his only known vices”, Grant doggedly helped piece together and maintain a secretive, highly disciplined organisation of a few hundred activists, each recruited with a religious intensity: first being sold the “Militant” newspaper, then being given further sacred texts, then being drawn into protracted discussions with earlier converts — the whole process taking as long as 18 months.

The internal culture of Militant, vividly brought alive by Crick, was austere and self-consciously proletarian: short hair, ties, hard work and early bedtimes, football and table tennis for relaxation rather than sex and drugs. In private and often in public, Militant had contempt for “trendy” causes such as feminism and nuclear disarmament, which were seen as distractions from the group’s historic mission of positioning activists strategically inside Labour and the unions, in preparation for the inevitable revolutionary moment.

This monochrome radicalism put Militant out of step with the brightly coloured politics of the 1960s. But the group’s seeming insignificance also meant that the Labour hierarchy left it alone. The 1970s suited Militant better: Britain’s increasingly erratic economy gave a greater appeal to its melodramatic policies and slogans, such as “Nationalise the 200 Monopolies”; and Militant’s aggression and ideological certainty seemed less odd in a more dogmatic and confrontational era. Membership grew almost tenfold between 1971 and 1980.

During the early 1980s, the press began to pay it more attention. But there were so many other leftwing bogeymen, from Tony Benn to Ken Livingstone, that Militant avoided sustained attack. Meanwhile, the leftward trajectory of Labour as a whole meant that those in the party alarmed by Militant had a hard time getting heard. Besides, to some less squeamish socialists, it seemed to offer an effective way to take on the increasingly dominant Thatcher government. In Liverpool, its capture of the council briefly promised to turn a neglected place with an electorally weak, rather rightwing local Labour party into a sort of leftwing city state, complete with ambitious urban regeneration plans and a Whitehall-baiting, supposedly revolution-hastening strategy of deliberate budget brinkmanship.

In the Liverpool chapters here, as throughout this involved but surprisingly addictive book, Crick’s sympathies are not with Militant. During the 1970s, he admits, the party snatched away a branch of the Labour party Young Socialists that he had set up. Yet he is balanced enough to point out that “Militant policies were quite popular with the Liverpool electorate”: it retained control of the council at the 1984 and 1986 local elections.

The more familiar story of Militant’s downfall from the mid-1980s onwards — the counterproductive city boss swagger of the Liverpool deputy council leader Derek Hatton; the Labour leader Neil Kinnock’s belated but lethal denunciation of Militant at the 1985 Labour conference — is told here in perhaps too much satisfied detail. But Crick cleverly spots that Militant got into trouble when it abandoned its original values: neither Hatton’s flashy suits and executive box lifestyle, nor the party’s faster recruitment, which led to less committed members and lots of defectors, were wise moves for a previously stealthy, careful organisation. In a sense, the Militant phenomenon became a classic 1980s bubble.

Yet even after Labour expelled Hatton and hundreds of other Militant “entryists” during the late 1980s, Militant retained a power. It formed the Anti-Poll Tax Federation, which organised the riotous demonstration in London in 1990 that helped end the Thatcher premiership. Militant survived a split, a name change and Grant’s death, aged 93. It even survived decades of bad-mouthing by another, more successful grouping that ruthlessly sought to seize and transform the Labour party: the Blairites.

Is Militant these days much more than just a useful ogre for Blairites or Tories? Crick doesn’t quite say. But last December, the pro-Corbyn movement Momentum issued a statement: “We can’t allow Momentum to be used as a vehicle for other parties. So if you are a member of the Socialist party ... for instance, you cannot also be involved in decision-making within Momentum.” We’ll see.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd

Andy Beckett’s “Promised You a Miracle: UK80-82” is published by Allen Lane.