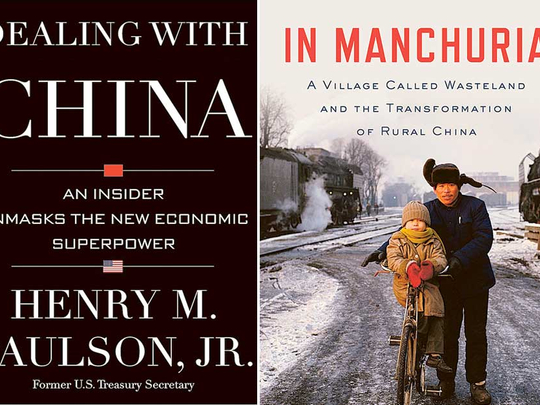

Dealing with China: an Insider Unmasks the New Economic Superpower

By Henry M. Paulson Jr, Twelve, 448 pages, $32

In Manchuria: a Village Called Wasteland and the Transformation of Rural China

By Michael Meyer, Bloomsbury Press, 384 pages, $28

Over the past century, many Americans have tried to interpret China for the West. The most famous was probably Pearl S. Buck, who earned a Nobel Prize for literature in 1938 for her novels about the suffering of the Chinese peasantry.

“Dealing with China” and “In Manchuria” are memoirs by contemporary Americans with long experience of China; both seek to extrapolate their own experiences into a wider message about today’s Middle Kingdom, and how the West should understand it.

The Chinas they examine are, at first glance, entirely different countries. Henry Paulson draws on his years as CEO of Goldman Sachs and then as US Treasury Secretary to tell a tale of his dealings with the country’s leaders. Michael Meyer spent months living in a tiny and remote village in northeastern China with the unpromising name of Wasteland (Huangdi). Yet read together, the books show that what Buck called these “several worlds” are inexorably linked.

The tone of Paulson’s book is evident from a compliment given to him by Wang Qishan, now a member of the Standing Committee of the Chinese Politburo, and Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption tsar: “You know how to get things done.”

Paulson has been close to some of the more prominent Chinese economic reformers, such as Wang and former premier Zhu Rongji, and much of the book is a highly readable account of their attempts to reshape China’s economy from socialism to a market-driven system, with Goldman Sachs’s chief executive given a starring role.

It might seem surprising that there was enthusiasm for learning from Western financiers in the 1990s, but this was the era when the Chinese Communist Party undertook its most aggressive privatisations, and the experience of American investment bankers proved invaluable in melting down China’s “iron rice bowl”. Paulson’s close contact with senior leaders produces some intriguing vignettes: Zhou Xiaochuan, the governor of the People’s Bank of China, is apparently a big fan of Broadway musicals and has compiled a guide to them (though sadly Paulson doesn’t reveal whether he bursts out in choruses of “If I Were a Rich Man” in the middle of meetings about interest rates).

Overall, the book succeeds in giving a rare and valuable picture of the Chinese elite, humanising these often mysterious-seeming figures. But Paulson’s friendship with the leaders means that he can, on occasion, soft-pedal the darker side of life in China’s top echelons.

Paulson describes his meeting with Bo Xilai, the former party chief of Chongqing, and recounts the lurid details of Bo’s downfall in 2012, but says little about what the scandal meant for the wider understanding of China. Yet it deserves further commentary: either a Chinese leader was brought down in a massive conspiracy by his peers, or else he and his wife, jailed for the murder of a British businessman, were involved in a web of corruption.

Either possibility suggests something unhealthy about the intrigues of Chinese politics. Surely a key question for anyone wishing to “deal with China” is to know whether the entrepreneurship and “can-do” spirit go hand-in-hand with the murkiness.

If Paulson gives us the view from the leadership compound, Meyer’s book shows us how those policies of privatisation have transformed the most rural and obscure parts of China, where the idea of meeting a Politburo member is about as likely as seeing an alien land (although one of the more colourful village locals claims to have seen exactly that).

The village of Wasteland is the birthplace of Meyer’s Chinese wife, Frances. While she made the understandable decision to learn English and emigrate to California, Meyer made the less instinctive opposite journey, moving into a house in the village to experience a rural way of life that was fast disappearing in China. Readers will be glad that he did.

Meyer’s book is a touching mixture of personal reminiscence and a primer on the history of one of China’s most significant regions, the northeastern provinces known to the West as “Manchuria”. The region was occupied by the Japanese in the early 20th century, and was ruled over by Puyi, the last emperor of China, who was restored as a puppet ruler of the state of “Manchukuo” between 1932 and 1945.

In more recent decades, its cities have experienced huge layoffs, and the rural areas are being turned over to commercialised farming. Meyer captures this fast-changing world with affection, but without sentimentality. “Unlike urban architecture,” he writes, “nothing in the countryside was ennobled by its age. Tools rust, weeds climb, roads sink, roofs collapse; nature always wins.”

Day by day, we read the details that show how village life — in China as elsewhere — often straddles the line between an intimacy that is cosy and closeness that is stifling. A schoolteacher finds herself trapped there for life; Meyer’s wife left early and has no intention of returning.

Paulson’s China is one of private jets; Meyer’s is one of outside loos. But there’s a clear connection between the stories they tell. For the economic reforms pursued so assiduously by Zhu Rongji and continued by the present leadership, assisted by Western advisers, have real effects in places such as Wasteland.

This century, the major change in the village has come from a company named Eastern Fortune, which is seeking to take over the local land and move the residents to new apartment blocks. This is not necessarily a bad idea; after all, modern sewers and power will be an improvement on what the village has now.

But the way that company is using its power has a distinct whiff of Beijing about it; this is a top-down process, not a consultative one, and village big shot “Boss Liu’s” decision to rename the village after his own company reflects a grandiosity that comes from a system where planners and technocrats’ visions tend to crowd out the quirky.

Paulson ends his book with a series of policy prescriptions about working with China. He seeks to answer the often hysterical anti-Chinese sentiment that can infect American political discourse. He goes on to make a series of sensible suggestions that help to explain why Chinese viewpoints do not always coincide with Western ones: for instance, pointing out that some of China’s reluctance to act against North Korea is because it does not want any prospect of a reunited, pro-American Korea on its border.

However, he also notes something that has become evident, and disturbing, to anyone who works with China: “When it comes to freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and expressions of dissent, Xi Jinping’s new administration is proving to be even more restrictive than its predecessor.”

The present clampdown on freedom of expression in China is evident to any tourist who switches on his laptop in Beijing and finds that a range of websites, from Facebook to Google to “The New York Times”, are simply blocked. It is an odd and ultimately self-defeating posture by a government that simultaneously argues that China needs to embrace globalisation, establish world-class universities and create a knowledge economy.

Even Meyer, in the farthest reaches of rural China, has run into problems caused by this suspicion of the outside world; at one point a visa officer can’t understand why he wants to live in such a remote place and accuses him of being a missionary (a banned category in China).

Perhaps these contradictions are unsurprising in a country that may soon put a person on the moon, but where nearly 100 million citizens still live on less than $1 (Dh3.67) a day.

–The Telegraph Group Limited, London 2015

Rana Mitter is the author of “China’s War with Japan, 1937-1945: the Struggle for Survival”