A new Harry Potter book has gone on sale, and it’s already the biggest literary event since, well, the last Harry Potter book. The difference is that the new story, the first since 2007, isn’t a novel.

Harry Potter and the Cursed Child is the script for the stage play, written by the playwright Jack Thorne, based on a story devised in collaboration with JK Rowling and director John Tiffany. The West End show, split into two parts, officially opened on July 30 to rave reviews, with The Telegraph’s Dominic Cavendish calling it “a triumph”. The text was released at 3am on Sunday in the UAE.

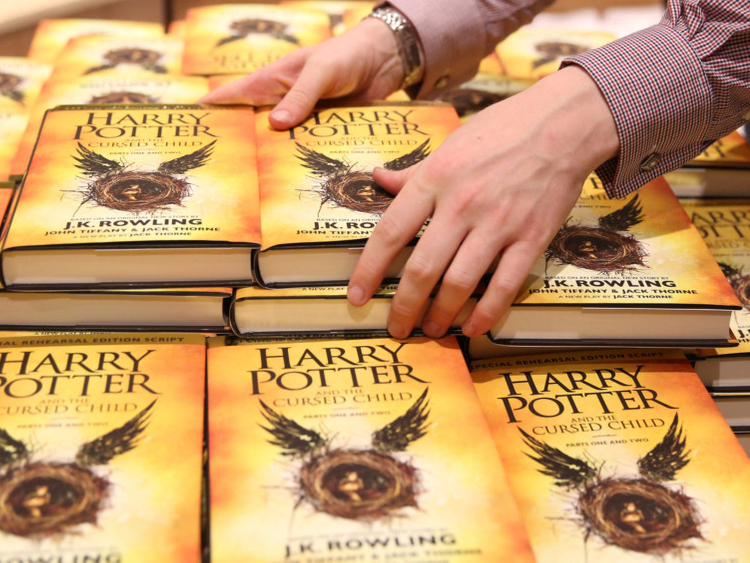

The publication has delighted both fans and booksellers, with James Daunt, the managing director of Waterstones, calling Rowling the “patron saint of bookshops”, and queues of customers snaking out of the doors at shops across the country as they wait to get their hands on a copy.

Though the theatrical run of the play in London will extend well into 2017, before a likely tour, the sale of the script enables the story — effectively a Rowling-sanctioned eighth instalment of the epic fantasy mega-franchise — to reach a far wider audience. Whether encountered on stage or on the page, this trip back into the magical world of Hogwarts is thrilling.

We begin where the seventh book left off, with a grown-up Harry, Ron and Hermione at King’s Cross station waving their children off on the train to Hogwarts. Harry and his wife, Ginny, say goodbye to their youngest son, Albus, who soon meets Scorpius, the son of Harry’s old school foe, Draco Malfoy. The developing friendship between Albus and Scorpius, forged partly through their shared sense of living in the shadows of their parents, is played out against a dizzyingly complicated time-travel plot.

Albus wants to prove himself — and set right one of his father’s failures — by going back in time, with the help of Scorpius, to save the life of Cedric Diggory, a victim from the fourth book of the series. But in their attempts to do so, the boys trigger a sequence of devastating alternate realities with far-reaching consequences. If you’re not familiar with the original books and characters, good luck following all this: the new story dives straight into the action, with no pause for recaps. But its combination of pacy plotting and wit-driven dialogue, though written by Thorne, feels fully part of Rowling’s vision.

Many favourite characters from the earlier books are revisited and even resurrected. One of the most successful things about the live theatre show is its jaw-dropping onstage special effects. It can be hard to visualise these through stage directions alone: the reader is left wondering how on Earth characters visibly become one another, exchange magical spells and transform objects into new things before the audience’s eyes.

More fundamentally, the stage show’s success rests on a combination of plot, performance, direction and sheer spectacle — on the page, the script feels like a skeleton of that overall intended experience. Having said that, as a reader, you have time to appreciate how nimbly Thorne’s writing navigates the adventure’s death-defying twists and turns. And his stage directions have a poetry of their own, a style that, in its lyricism and sense of the abstract, is distinct from Rowling’s more direct, story-driven prose.

For example, when Albus arrives at Hogwarts and is sorted into his school house, we are told: “There’s a silence. A perfect, profound silence. One that sits low, twists a bit and has damage within it.”

When the children travel in time, Thorne’s stage direction notes how, “time stops, and then it turns over, thinks a bit, and begins spooling backwards”.

At its best moments, it reminded me of reading JM Barrie’s beautiful script for the 1904 stage play of Peter Pan. As a story containing many possible alternate realities, with a text created to varying degrees by three collaborators, Harry Potter and the Cursed Child is a complement to Rowling’s original series rather than a straightforward continuation.

It won’t satisfy all fans: some have already taken issue with the story’s extensive reliance on time travel, the use of which seems to disagree with the magical precedent set in the books. Others have quibbled with the portrayal of Harry’s character: he comes across as pricklier and even more troubled than he was in Rowling’s books. But the emotional climax is devastating even on paper.

Once again, the fantasy world that Rowling created nearly 20 years ago is at its most powerful when it sets aside magic and reveals the simple, brutal and human mechanics of love and grief. The characters are, mostly, exactly as you remember them, and it’s difficult to overstate how exciting it is to read a new story set in this widely loved fantasy universe. The thrill of a new Harry Potter book, even in script form, is its own kind of magic spell.